Felt Impressions

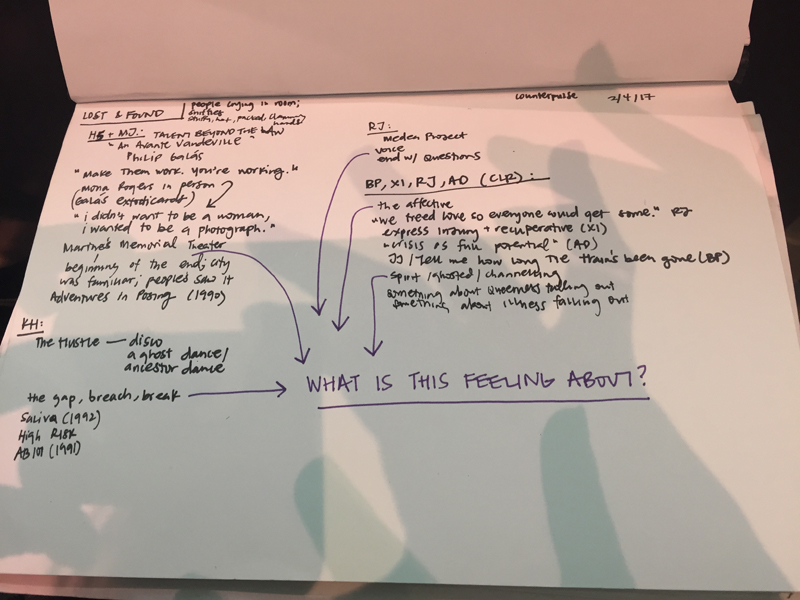

On February 4th, 2017, Open Space presented an afternoon of conversations and performances at CounterPulse, as the culmination of this Lost and Found series. After my brief introduction, the day unfolded with Monique Jenkinson and Helen Shumaker in conversation; a performance lecture by Keith Hennessy; and a short presentation by Rhodessa Jones, who then joined a panel discussion with Annie Danger, Xandra Ibarra, and Brontez Purnell. That conversation spun out of the theater and into the streets, transforming into a SpiritualDiscoGrievingDanceRitual led by Amara Tabor-Smith and featuring Brontez Purnell and Marvin K. White. Among the audience members that day were Sampada Aranke, Kelly Lovemonster, and Margaret Tedesco, each of whom we asked to respond, however they wanted, to their experiences. –clr

There was an unmistakably confusing feeling during Lost & Found. I could hear sighs and sniffs, audible annotations of affects that would be kept quiet in another place, with another crowd. But something else was in the room that day; something unbearably present and awkward, yet touching and sweet. It was mobilized through an inability to talk about what we were talking about, an inability to account for a feeling so overwhelmingly present and far away that even while we attempted to do it, it was an impossible task — an exercise in the failures of grief and celebration, memory and history, presence and absence.

I needed help finding the language to even think about those feelings, so I looked elsewhere for a clue. In her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sara Ahmed offers a striking composition of queer life practices that entangle feeling as central to the distribution of non-normative affects. At one point, Ahmed meditates on loss, thinking through the implications of life and death as formative to contemporary queer experience. She proposes a language of impressions to discuss the politics of remembering and inheritance:

So to lose another is not to lose one’s impressions, not all of which are even conscious. To preserve an attachment is not to make an external other internal, but to keep one’s impressions alive, as aspects of one’s self that are both oneself and more than oneself, as a sign of one’s debt to others. One can let go of another as an outsider, but maintain one’s attachments, by keeping alive one’s impressions of the lost other […] Although the other may not be alive to create new impressions, the impressions move as I move: the new slant provided by a conversation, when I hear something I did not know; the flickering of an image through the passage of time, as an image that is both your image, and my image of you. To grieve for others is to keep their impressions alive in the midst of their death. 1

Impressions allow us to inhabit a set of feelings around a loss, to tarry within our memories and our feelings. Ahmed mobilizes the image here as the object through which this relationship is consolidated. This image fades in and out of view, invokes emotion, and locates one’s relationship to those lost. What strikes me here is Ahmed’s adoption of the visual object as a method of thinking through impression. Image is what mediates a memory through the presentation of how one remembers the lost — through memory incorporated by sight.

I would contend that impressions are incorporated beyond memory, and, I would say, make themselves felt at the level of the body. Image might incite or abstract the presentation of affect, but the notion of impression itself necessitates weight, gravity, and touch — all critical modalities that the body enlivens. To impress upon is to use a body’s weight to leave an impermanent trace, a fleeting moment where the ways we are touched leave unseeable marks. The gravity of loss is activated in that sinking feeling, the way our hearts drop into the pits of our stomachs, and the delay between what our bodies do and when our minds catch up in the wake of loss.

This might be exactly what is found in the inheritance of loss. This is the affective material that is carried within the body and precisely what was activated in the room. Best lived in the impossibility of naming those feelings, we can think of those lost as impressed upon us in memory and flesh, image and touch, knowing and feeling.

Comments (1)

Powerful and profound. Thank you.