Insist, Persist, Resist: An Invitation to Action for Women’s Liberation

-

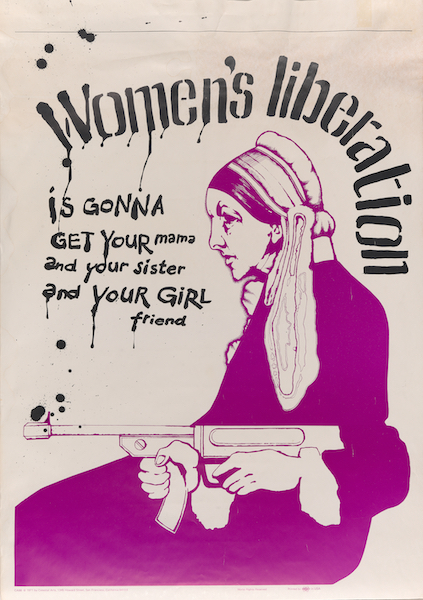

Women’s Liberation Is Gonna Get Your Mama and Your Sister and Your Girlfriend, 1971

-

Untitled, ca. 1975

Over the years, as an activist working to develop the field of women’s studies (now most often called gender and women’s studies), I saved posters from the women’s liberation movement and our allies. The choice of posters was random, in the sense that I did not intend to create a collection; I saved a poster primarily because it energized and inspired my passion for justice, through its message, or design or through the memories of the event it is announcing. In short, I wanted it near me.1 I purchased some and a few were gifts from friends, but the majority I picked up after an event was over and the posters were left behind. These art works were doing their job: they had a certain glow that attracted me. In her introduction to The Art of Revolution: Castro’s Cuba, 1959-1970 by Dugald Stermer, Susan Sontag, one of the few prominent critics writing on political graphics, distinguishes posters from announcements by saying that the latter simply impart information while posters aim to seduce you to action.

A new poster would decorate my house for a while, then be relegated to my attic or storage unit, in whatever box was available. I might not have thought about it again for years, except every now and then, when it had to be rescued from mice who wanted to shred it for nests. I don’t know why I bothered to keep so many posters — 128 — over fifty years; it just seems to be my nature. Bobbi Prebis, my then girlfriend, now spouse of forty-three years, accuses me of never having seen a piece of paper I haven’t wanted to save. Although there might be some truth to that, it is also true that in the twentieth century there was a significant rise in ordinary people creating collections, and poster collecting became fashionable. Sontag attributes this to capitalism’s ever-increasing need to sell goods. Everything — even our political expression — is turned into a salable object. It is likely I was influenced by this trend without being conscious of it.

In 2017, my relationship to these posters radically changed. By chance, on a trip to San Francisco from my home in Tucson, I saw Get With the Action, a small poster exhibit at SFMOMA displaying a selection of political posters from the 1960s to the present. I thought to myself, “I wonder if the curator, Joseph Becker, would be interested in my collection.” I wrote to him, and much to my surprise he wanted to see everything I had. To share them in an organized fashion, I had to index, photograph, and create a database for the original 128 posters. Since I was not trained in this kind of work, nor did I have support staff who were, the effort took me more than two years (despite the generous help of a number of volunteers and short-term workers). No wonder people throw away posters and other ephemera — it’s too much work to preserve and interpret them!

-

Strategies for Survival, 1975

-

Women Declare War on Rape, 1977

In December 2019, Joseph let me know that SFMOMA was interested in acquiring a selection of my collection for the museum’s permanent collection, with the intention of exhibiting ten to twelve of them from October 2020 — in time for the presidential election — through March 2021. After some discussion regarding the selection, we agreed on my donating seventy-two posters. The Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy Collection of Women’s Liberation Posters was born.2

My collection “shows off” the astonishing breadth of the women’s liberation movement and the mark it has left on today’s world. In my mind, these posters address at least ten major issues: 1) consciousness raising about women’s oppression; 2) activism for ending male supremacy, racism, and capitalism; 3) building institutions like women’s studies; 4) fighting for reproductive rights and justice; 5) struggling for LGBTIAQ liberation; 6) solidarity with liberation struggles around the world; 7) celebrating International Women’s Day; 8) labor activism; 9) organizing for peace with justice; 10) promoting art as practice: breaking silence. There is an eleventh issue that cross cuts these categories: the struggles of women of color to have their voices heard, their perspectives included, and their activism supported. Their situation is expressed elegantly by Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith in the title of their 1982 anthology publication, All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies.

Despite the variety of posters, my collection cannot claim to be representative of all aspects of the movement. There are just too many paths to women’s liberation for that to be the case. For instance, as an anthropologist who had done two years of fieldwork in Colombia from 1964-1966 with the Wounaan people, I brought to the movement my interest in supporting and expanding Indigenous struggles against imperialism, and by extension all oppressed nations’ struggles against US domination. Therefore, these areas are more fully represented in my collection than others. Similarly, since I lived in Buffalo, New York, from 1969 until 1998, I was more likely to see and acquire posters from that region of the country; even though this was definitely a national movement, and posters from elsewhere made it to Buffalo, and Buffalonians traveled for movement events.

The collection began in 1970, when I became active in women’s liberation. I selected 1999 as the end date so that the collection would include posters from both the early, most radical moments of the movement, as well as from more conservative times. By 1980, with the election of Ronald Reagan, liberation movements were actively repressed, through attacks on reproductive rights, social welfare programs, and air traffic controller’s union organizers. This conservative shift extended beyond the president, just as Phyllis Schlafly’s organizing to defeat the ERA began before Reagan’s election. By 1990, neoliberalism was well on its way to monetizing all human transactions and erasing visions of justice and equality.3

As I worked to organize the posters as a collection, the energy that originally attracted me to them intensified. They pulled me into their stories. It began to dawn on me that these posters could be useful in educating people about the mid-to-late twentieth century mass movement of women, with the support of some men, that challenged the oppressive restrictions in all areas of women’s lives and put forth a vision of justice. They captured that magical combination of theory, practice, history, solidarity, and oppression that ignites a social movement and makes it possible to challenge entrenched hierarchies. In what looks to be the end of the Trump era, this combination feels far from our daily experience and hard to imagine. Yet as I write this l am beginning to think that the Black Lives Matter movement might be heading in the direction of becoming a mass transformative movement.

Today, most people, following a view popularized in the media and consistent with dominant political ideas, take for granted women’s gains in achieving equality over the last century. They see social justice, at best, as something that evolves naturally — after all, we live in the US, where “everyone is equal” — or, at worst, as given to us out of the generosity of men in power, rather than the result of organized collective struggle and mass demonstrations over many years.

-

The Liberty Tree, 1976

-

International Women’s Solidarity, 1975

Posters are an effective way to convey a counter view: that the late twentieth century was a deeply radical period in US history, with anti-war movements, civil rights movements, women’s liberation or multiracial feminist movements, gay liberation movements, labor movements, anti-imperialist movements, and disability rights movements (to name a few) all challenging hierarchical structures. Like myself, many people brought knowledge and practices from other movements to women’s liberation, broadening the vision of justice and the strategies for achieving that justice. Equally important during this period were the many different tendencies (including African American womanism, women of color feminism, chicanx feminism, lesbian feminism, socialist feminism, radical feminism, lesbian separatism, and women’s rights feminism) that deepened our understandings of power hierarchies and the impossibility of separating any one issue from the others. Women of color activists and scholars made the radical (and once named, obvious) claim that it is not adequate to conceptualize women simply through the lens of the oppressive forces of the patriarchy. Naming racism is equally important. Intersectionality remains central to activism and scholarship today.

I use the term “women’s liberation” to include all of these different feminisms, because no one approach captures the power of women’s challenge to patriarchy, racism, and capitalism in this time period. By inclination and scholarship, I identified most with socialist feminism, as can be seen by the centrality of international struggles against imperialism and by my emphasis on interlocking systems of oppression in the collection. At the same time, my vision of feminism included the amazing insights and practices of woman of color feminism, radical feminism, and lesbian feminism.

In my memory the mix of ideas was stimulating and productive, all in the spirit of making a better, more just, world. Most likely, nostalgia for the excitement of the period has taken over my mind; with so much at stake — ending the Vietnam War, ending the oppression of women, defending communities of color against police harassment — the disagreements were not usually friendly, the conflicts understandably heated and stressful. Activists’ challenges to state, corporate, and male power had real consequences; they could lead to the loss of a job, divorce, incarceration, or even death.

As an educator, I am always looking for tools or props to help people imagine what it would be like to live in a particular time period or culture. In this case, to be part of a mass movement that acknowledges the hierarchical systems of race, class, and gender working together — one that believes change will require direct challenges to these systems by a critical mass that takes over the streets, if necessary. Posters help us to understand the passion and energy that empowered women’s liberation, giving participants the confidence to think we could change the world and run a country on principles of peace and justice. By extension, I hope that this particular collection of posters leads people to check out the Black Lives Matter movement that is growing all around us, forging a pathway towards ending structural racism in the US and the world.

Enough of an introduction. I hope you enjoy the posters.

[Insist, Resist, Persist: Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy Collection of Women’s Liberation Posters from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s is scheduled to be on view on the museum’s second floor into May 2021. No ticket is needed to view the exhibition.]

-

No More Fun and Games, ca. 1972

-

If You Want It Done Right, Hire a Woman, 1973

-

Poster for the exhibition “¿Dónde están?” (Where Are They?), n.d.

-

I’ll Be There (National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay People), 1979

Note: For scholars and students of women’s liberation, these posters are accessible by appointment with the museum’s Collection Study Center. I have provided a slideshow with commentary on the seventy-two posters that remains accessible with the collection as well as the database. Images of the individual posters will be visible on the museum’s collection pages.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Harrison Apple for bringing his skills with and creative thinking about queer archiving to this project. Without his help, I am not sure this project would have been completed. Thank you also to my feminist and queer colleagues in Tucson for their feedback on this introduction and on the collection, including but not limited to Ethne Luibheid, Hai Ren, Judith McDaniel, Jan Schwartz, Deb Edel, Teddy Minucci, Adela Licona, Jamie Lee, Sande Zeig. Also thank you to Sherri Darrow, Margaret Small, and Peggy Baker for sharing their experiences as activists in women’s liberation, and Joan Nestle for giving me a story when I foolishly assumed there wasn’t one. A special appreciation to my spouse Bobbi Prebis, for putting up with the posters trailing us in our moves and taking up living room space during the months I tried to sort them.

- In selecting the posters to save, I didn’t explicitly consider design quality, because I am not qualified to make such judgments. However, it is fair to say all were attractive enough to grab my attention. As I did background research I learned the creators were at different levels of artistic accomplishment. Reflecting the era’s interest in countering competitive individualism, only a little more than a quarter of the posters were attributed to a named artist and the rest were either attributed to a graphic arts collective or had no mention of the creator.

- From the beginning of our discussions, I made it clear that I was only interested in donating the posters to an institution that would make them available to the public, by listing them in an online database that regular people could access. Also, the cost for using the archive had to be reasonable, which Joseph assured me was the case; the posters are currently on view in the museum’s free public space on the second floor.

- I would have liked to arrange the posters chronologically in order to develop a precise timeline of movement events and poster aesthetics, but this was not possible since slightly fewer than half of the posters are undated.

Comments (8)

-

Julie Boddy says:

March 27, 2021 at 6:50 am

-

Wendy Smiley says:

January 30, 2021 at 9:14 am

-

Debra Ann Gould says:

January 29, 2021 at 5:56 pm

-

Carolyn Korsmeyer says:

January 29, 2021 at 5:13 pm

-

Marcia Biller says:

January 29, 2021 at 11:09 am

-

Margaret Small says:

January 29, 2021 at 8:07 am

-

Judith McDaniel says:

January 28, 2021 at 6:36 pm

-

Barbara Horscraft says:

January 21, 2021 at 10:05 am

See all responses (8)What a wonderful gift! I’ve hung on to quite a few myself. Now I better understand why. Thanks always for your inspiring vision and dedication.

Well done Liz. Thank you for preserving our history. And bringing back memories.

What a great project Liz! Sherri turned me on to it. How precious for us all that you saved these posters. You have so clearly reminded me of my roots in socialist feminism and you continue to inspire me through your continued dedication to peace and justice and community. You are the best teacher ever!

I am so pleased, Liz, that you have found a home for these fascinating posters! Thank you for making them available in this way. I’m sure their historical importance will be of growing and enduring interest for many years to come

Wow Liz! what a wonderful project. Takes me back to my roots of social activism and reminds me what a force you were are are.

This collection is such a gift to activists and women. Liz Kennedy is an exceptional teacher, scholar, activist, human being and friend. One of the many heroes of our movement over the past 50 years

What a wonderful and vivid way to remember the work done in the last century that brought us into this one. I love the vibrancy and immediacy of both the poster’s and Kennedy’s description of the work the posters were doing.

Very interesting… Looking forward to seeing more. Thank you .