Nothing To Sell: On Reese Palley Gallery

Carol Lindsley and Reese Palley, ca. 1969.

Commissioned on the occasion of The Brief, Largely Subterranean History of Reese Palley Gallery, San Francisco, 1969–1972, an exhibition on view at Cushion Works from February 29 to April 4, 2020.

•

This is the story of the Reese Palley Gallery, a story of porcelain birds and radical art that co-existed inside Frank Lloyd Wright’s only San Francisco building. Any account of the gallery, which opened in 1969 and closed in 1972, must begin with Reese Palley (1922–2015) himself, a larger-than-life, Atlantic City-born entrepreneur, adventurer, author, and art dealer who launched his career in art as a promoter of elaborate sculptural birds by Edward Marshall Boehm, whom he dubbed “the Louis Comfort Tiffany of porcelain.” Palley initially sold the birds in the hometown gallery he opened in 1957 along the city’s famous boardwalk. Business boomed. In short order, the son of a Russian immigrant watchmaker and a graduate of the London School of Economics began branding promotional content like catalogues and matchbooks with a new moniker: Reese Palley: Merchant to the Rich.

At a Pacific Heights cocktail party in 1969, Palley encountered a young, charismatic, Ivy League-trained fundraiser named John Gooding, who had recently arrived from Pittsburgh to work for American Conservatory Theater. The idea for Palley West came from Gooding, who was promptly hired as its director. Palley leased and renovated Wright’s 1948 masterpiece (a former V.C. Morris jewelry store) on Maiden Lane, a tony downtown alley. The small brick building with its distinctive arched entry featured an interior spiral ramp to the second floor, predating Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York by more than a decade.

An advertisement for Reese Palley’s Atlantic City gallery, ca. 1950s.

Gooding, in turn, hired Carol Lindsley as the curator, affording her carte blanche. A UC Berkeley art history graduate, Lindsley was fresh from organizing Plastics West Coast for the notable Hansen-Fuller Gallery in San Francisco, an exhibition billed as “San Francisco’s first total show of the revolutionary space-age media.” The show, which presented Bay Area artists exploring plastics like resin and vinyl in complex and novel ways, received critical attention in Art in America, ARTFORUM, and the San Francisco Chronicle, where critic Alfred Frankenstein wrote that Lindsley is “greatly to be congratulated” and “no museum could have done it better.”

Lindsley initially mounted exhibitions of contemporary artists along the interior ramp, including Billy Al Bengston/Ed Ruscha in 1969 and Some New York Painting, featuring Brice Marden and Lee Lozano, among many others, the year after. It was soon clear, however, that flat works didn’t sit especially well on the curved walls, so Lindsley and Gooding converted the cellar into a gallery more suited to the new Conceptual practices which increasingly attracted Lindsley.

With Palley’s blessing — and relative physical absence on the West Coast — in 1969 they engaged Wayne Campbell, another Berkeley graduate, to build out the space and inaugurate what they called the Cellar Gallery. A series of groundbreaking shows followed, and when the gallery relocated in 1971 to a larger space on nearby Sutter Street, it was divided to allow for Lindsley’s pursuits and Palley’s Boehm birds.

Stephen Kaltenbach, Sunset, 1970–71. Courtesy of the Crocker Museum.

According to Gooding, the gallery was closed in 1972 after more than two dozen exhibitions for what Palley described only as “economic reasons.” Palley’s New York City branch on Prince Street, founded in 1970 as one of the first galleries in what became known as SoHo — and home to many exhibitions by California artists — closed the same year. With typical flair, Palley divested himself of his possessions, wrote books on nuclear power, concrete, and more, and for the next twenty years traveled the seas in his boat, aptly named “Unlikely.”

It is hard to overstate how small the San Francisco art world was in the late 1960s, especially among its vanguard constituency. Reese Palley was the sole commercial gallery to show this new, largely unsalable work — indeed, it was one of the only places, commercial or nonprofit, that even ventured into such unfamiliar territory.

Overlapping with this underground program was artist Tom Marioni’s Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), founded in 1971 just south of Market Street, then a no-man’s-land as opposed to the stylish locations of Reese Palley. MOCA served as an artist’s clubhouse with remarkably fertile ground for risk-taking in performance, video, and installation. Pre-MOCA, as director of the East Bay Richmond Art Center from 1968 to 1971, Marioni presented radical actions and installations by the soon-to-be leading local Conceptualists, including Terry Fox, Howard Fried, Paul Kos, Dennis Oppenheim, and himself (under the pseudonym Allan Fish). Temporal, personal, psychological, occasionally confrontational, these artists would also be shown at Reese Palley.

Another key player was UC Berkeley curator Brenda Richardson, who organized exhibitions in a campus gallery before construction of the University Art Museum in 1970 (now the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive). One of Richardson’s more memorable exhibitions was The Eighties (1970), in which artists presented works reflecting on the future. At the opening, as protest and warning, Fox torched a plot of jasmine plants in front of the museum; the United States had more troops than ever in Vietnam and news of the My Lai massacre had recently hit. Richardson mounted a major Fox exhibition at the newly built museum in 1973; other Eighties artists who overlapped with Palley were Fried, Jim Melchert, and Robert Kinmont.

Several Palley artists studied, taught, or exhibited at the San Francisco Art Institute, where Fried founded the influential performance and video department (now New Genres) in the late 1970s. By that time, a few adventurous non-profit spaces had opened, including 80 Langton Street, Camerawork, Southern Exposure, and Galería de la Raza. The Bay Area was now established as a major center for emerging practices.

Lindsley’s programming reflected the emergent characteristics of Bay Area Conceptualism, marked by a full range of new genres, but with an emphasis on performance and ritual. Artists shifted from object to event, film, and video, reimagining time as medium. Bay Area Conceptualists generally relied less on systems and linguistic structures than their New York peers. Instead, they drew their art and lives close, often erasing the distinction between the two. In this regard, they shared an affinity with Europeans such as Joseph Beuys and Italian Arte Povera artists who privileged non-art materials like ice, dirt, and rocks.

This rejection of systems in favor of messier, more immediate elements was surely influenced by San Francisco itself, a city that, since the mid-1960s, had been at the forefront of cultural and political dissent. While Palley artworks were seldom overtly political, artists were clearly affected by the revolutionary spirit of the time, which included a rejection of the commercial concerns of the mainstream art world (though it’s worth noting that the status quo of an art world that mainly supported white, male artists continued here). In the Palley Cellar, there was simply nothing to sell.

But there was history to be made. Bruce Nauman’s Corridor for San Francisco (Come Piece) (1969), one of the artist’s first corridor installations, launched an entire body of architecturally related works. Nauman received his MA at UC Davis in 1966 and left the Bay Area just before his Reese Palley show, which also featured his film projection, Art Make-Up, in which he paints his naked torso. While Nauman never crossed paths with the artists who became the core of the Bay Area Conceptual movement, his work had a critical impact on many of them.

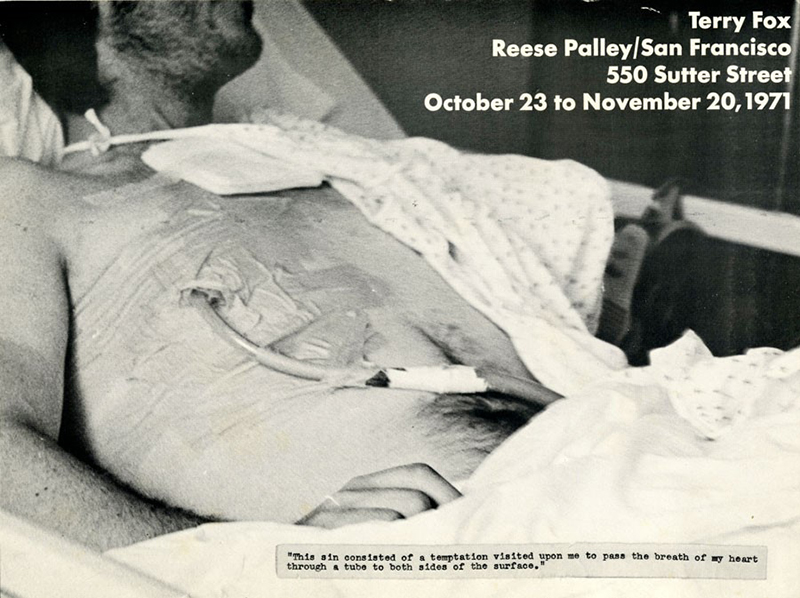

Indeed, Fox remarked that experiencing Art Make-Up gave him the very idea of using his body as a material. The artist had two exhibitions at Palley and performed several actions at the first, including Opening My Hand as Slowly as Possible, Corner Push, Asbestos Tracking, and Impacted Lead, the latter of which consisted of firing bullets in as straight a line as possible to form a small bar of lead in the wall. For Hospital, his second show, Fox created an environment which metaphorically communicated his experience suffering from Hodgkin’s Disease, a blood cancer that starts in the lymphatic system. This starkly dramatic environment included partially erased blackboards chalked with figures relating to the costs of medical care, a white enamel bowl and cloth, a bare hanging light bulb, and wires snaking across the empty white floor to two tape recorders that reproduced the sounds of Fox breathing and chanting.

A still from Bruce Nauman’s Art Make-Up, 1968.

In 1970, Stephen Kaltenbach, who attended UC Davis alongside Nauman but was then living in New York, traveled back to San Francisco to create an installation for Reese Palley consisting of two rooms, one comfortable and dimly lit, the other exceedingly hot and bright. The “star room,” as Kaltenbach called it, was painted with ten thousand Lumina dots on the walls, floor, and ceiling. Visitors sat on pillows in total darkness until their eyes adjusted and stars enveloped them in limitless space. Recently, Kaltenbach reflected that he wanted visitors to feel “adrift.” The hot room was fitted with the brightest bulbs available, warmed with a sauna heater, and covered with reflective paint. His second show, which took place on Sutter Street, included Sunset, a small painting inspired by a sunset he saw as he was driving, stoned on hashish, from New York to California. While Nauman soon became world renowned, Kaltenbach eschewed the limelight, leaving New York for Northern California, where he lived and taught for the next several decades; he has recently re-emerged with exhibitions at Pierogi and Marlborough galleries in New York, and The Beginning and The End at the Manetti Shrem Museum at UC Davis (co-curated by Lewallen and Ted Mann), a large survey of work produced over a fifty-year span.

Kos took advantage of Maiden Lane’s two stories for the iconic Sand Piece, exploring the kinetic properties of natural materials. To realize the work, Kos poured a literal ton of sand on the second story of the gallery, which filtered through a small hole in the floor over the course of days — a larger than life hourglass — to form a crater-like mound on the Cellar Gallery floor. Lindsley didn’t balk at the work’s ambitious scale; Kos recalls that the curator was always open to challenging ideas and “generously agreed […] allowing me to set my concept into form.” He also premiered Roping Boar’s Tusk, a film in which he plays the cowboy vainly and romantically attempts to rope a distant volcanic plug.

Fried had two exhibitions of key works, the video Sea Sell Sea Sick at Saw/Sea Soar, a vertigo-inducing restaurant scene, and Sea Quick, a performance video exploring conflict resolution by two people on a heavily greased seesaw without handles. His second show featured the iconic Fuck You Purdue, a video in which he plays the twin roles of warring Marine Corps drill instructors, Ward and Purdue.

Reese Palley’s San Francisco history has never fully been told for several reasons. First of all, and literally speaking, there was very little to hold onto; performances, by definition, were durational in nature. Further, works were self-documented, if documented at all. The ephemeral nature of the project was compounded by Palley’s eventual abandonment of the art world (and the land-based world, for that matter). Gooding, who stayed in the Bay Area, went on to make a robust career in political consulting. Shortly after the closure of the gallery, Lindsley moved to Baltimore, where she taught at Goucher College and developed a painting practice, which she continues to this day.

The varied practices fostered by Lindlsey were conceived well before video and performance works had their place in national and international exhibition programs, let alone art history books. Although active for a scant three years, the Reese Palley Gallery’s brilliant, unconventional, and innovative program provided a model for countless venues that followed, in the Bay Area and beyond.

•

A list of the Conceptual exhibitions that took place at Reese Palley Gallery in San Francisco:

Maiden Lane

Wayne Campbell, September, 1969

Bruce Nauman, December 9, 1960–January 10, 1970

Joel Glassman, February 10–March 7, 1970

Stephen Kaltenbach, March 13–April 14, 1970

Liz Phillips, March 4, 1970

Terry Fox, May 19–June 13, 1970

Howard Fried, June 16–July 11, 1970

John C. Fernie, July 15–August 8, 1970

Dennis Oppenheim, October 27–November 21, 1970

Bob Kinmont, March 17–April 10, 1971

Paul Kos, April 14–May 7, 1971

Linda Trauth, June 7, 1971

Peter d’Agostino, January 26, 1971

•

Sutter Street

Nancy Graves, September 11–October 16, 1971

Terry Fox, October 23–November 6, 1971

Mabou Mines, November 23, 1971

Stephen Kaltenbach, January 10–January 29, 1972

John C. Fernie, February 1–March 4,1972

Howard Fried, March 11–April 8, 1972

Klaus Rinke, April 15–May 13, 1972

Tom Marioni, April 16–May 13, 1972

James Melchert, May–June, 1972

John Woodall, June 28–July 29, 1972

Gallery Closed, August 17, 1972

Comments (3)

wow. Thank you.

This is a terrific history. Thank you both so much I feel like it’s just a testimony to the fact that one person or a small space can really have an outsize impact. Eugenia Butler is another individual who put great artists together at her gallery from 1968 to 1971 (including a show at SFAI in 1969). Similarly the Ferus Gallery had a huge impact during a turbulent decade 1957 – 1966. All these smaller operations and the people behind them like Reese Palley paved the way for a whole branch of intellectual art & developed the audience for it. The world would be a much less interesting place without all that they did.

A few additional illustrations of Reese Palley Gallery exhibition ephemera from the SFMOMA Library: https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2012/09/receipt-of-delivery15/