“Take hold the crackling power”

Lynn Lonidier’s author photo for A Lesbian Estate. Photo: Fred Lonidier.

Few readers of poetry these days — even if they’re poets or artists themselves — likely recognize the name Lynn Lonidier. A fascinating figure from the San Francisco arts scenes of the 1970s and ’80s, Lonidier’s gender-bending experimental poetry serves as exciting precedent to the pioneering work of writers such as kari edwards and Eileen Myles, along with younger poets celebrated in Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics. For Lonidier, it is writing that makes living possible; as she declares in her 1979 book Woman Explorer: “It is for the risk of living, I call myself a poet — to survive.” Her work is the record of her struggle to exist in her body apart from the reductive impositions of the cloistered society of her time; as a result, it is ever in conflict with the heteronormative world surrounding.

Archived at the Gay and Lesbian Center in the San Francisco Public Library, Lonidier’s papers span 1958 to 1993 and hold several unpublished manuscripts, including poetry, essays, and a number of novels. Here is the short version of the biographical note appended to the Finding Aid:

Lynn Lonidier was born in Lakeview, Oregon on April 22, 1937. Often describing herself as a “card-carrying anarchafeminist,” Lonidier was a teacher, author and multimedia and theater performance artist. As a West Coast writer, she was active in the San Francisco literary scene, especially within the lesbian/feminist community, during the 1970s until the time of her death in 1993. Also a musician, she studied composition and collaborated with Pauline Oliveros at the University of California at San Diego. She also attended San Francisco State University where, as a cellist, she majored in performance. She also received a M.A. in Media/Education in 1975 from the University of Washington at Seattle.

It’s odd that she is not directly identified as a poet: this is, after all, an individual who’s been called “perhaps the first true avant-garde lesbian poet after Gertrude Stein” by no less a revered commentator on innovative poetry than Ron Silliman. Her work, however, resists easy categorization, as her own thoughts regarding Stein demonstrate:

“Influences / Lorca / Rilke / Emily Dickinson / Hart Crane / These are the ones / I try to write like / NOT / Jack Spicer — never heard / of him / Gertrude Stein — I didn’t / want to wade through / that stuff”

And also:

“I am a Gertrude Stein without money / How does she write without money / She owns her own house / How does she keep her home without money / that accounts for the difference / in styles to the last word” Handwritten notes by Lonidier, The Lynn Lonidier Papers (GLC 1, Carton 1, folder 37), Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library. Special thanks to librarian Penelope Houston.

Full of surprising oddities and ever-shifting styles, Lonidier’s work investigates concerns immediate to her own affairs. The obscuration is both deliberate and necessary.

Not that she didn’t at first attempt more conventional forms. Among her earliest published poems, possibly her very first is “Sow,” which appeared in the Spring 1962 issue of The Massachusetts Review. It is a portrait poem, straightforwardly describing a mother pig “from the ground / motionless, but constant / as a potato” appearing with her young who “seep into / her core, her white earth.” One imagines Lonidier witnessing this scene firsthand. Demonstrating a fine working knowledge of such MFA millhouse ideals of “craft,” it’s a poem easily passed over and forgotten.

By 1967, Lonidier had shifted focus. Her first published book P O T R E E (Berkeley Free Press) embraces juxtaposition of words with images in a collage of visual stimuli reminiscent of Dadaist publications from a half century before. Lonidier’s own “illustrations,” as noted on the title page, are complemented by original drawings from sisters Betty and Shirley Wong. The book is wonky and fun. One page offers a series of images detailing the farm-to-table saga of many a pig: there’s a child feeding a pig followed by a butcher’s diagram of varying cuts of meat on the animal’s body, which is labelled “USA,” and at bottom a strip of bacon bearing uncanny resemblance to the state of California, labeled “California.” Floating over all of this are eleven incongruous lines, including “JET POET CORPSE LOOK OPEN FIELD,” “FASHIONABLE NUTBOWLS,” and “STARSPANGLED LEVER LEAP.” This near-sonnet could also be described as a cut-up poem; whatever else it may be, it definitely mocks the earnest and distinctly American air of self-importance.

From P O T R E E (Berkeley Free Press, 1967).

Lonidier was brought to my attention just a year ago by poet Richard Tagett. Over dinner at our house, Rich spoke so strongly of Lonidier’s work that I became immediately interested. He specifically mentioned A Lesbian Estate, published by Manroot in 1977 and featuring cover art by Jess. Sure enough, later that evening when I took a second look in Siglio Press’s Jessoterica book, there it was, a gorgeously intricate paste-up.

Measuring 10” x 7” with warmly inviting purple endpapers and interior pages printed on heavy paper stock, A Lesbian Estate gathers the majority of Lonidier’s work from the 1970s. I believe it to be her strongest collection. Here are her poetic expositions on the hermaphrodite:

From A Lesbian Estate.

“Light” is one of Lonidier’s central motifs, a natural extension of her filmmaking and experimental multimedia work. In her unpublished essay “The Facts Are, The Poem Is” she announces: “What is the difference between making a poem and making a film. None. […] I only recently determined almost every poem I ever wrote makes reference to light or has the sun in it. […] It is in the cold light of truth I would like to face my life’s circumstances.” This gritty determination to measure her work against her own personal experiences “in the cold light of truth” is what makes reading Lonidier’s poetry, at its most compelling and convincing moments, so riveting.

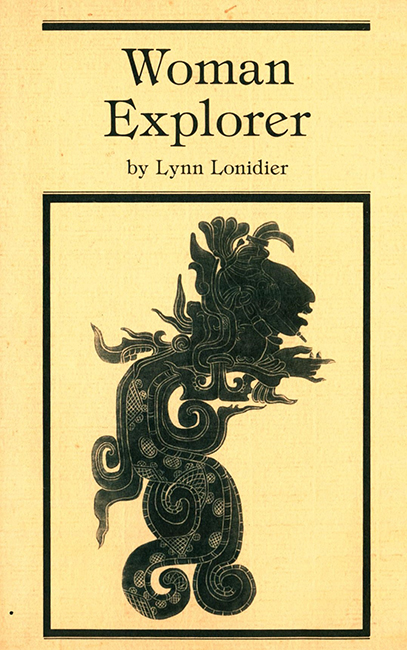

This determination, coupled with a “restless” intellect, are on full display in Woman Explorer, which poetically documents her trip to Mexican archaeological sites, as well as reflections of the continued pull of hermaphroditism:

I once told Robert and Jess to go to the University of California medical library and ask to see the case histories on hermaphroditism. Now I would tell them: Go to Mexico and see the pyramids. Jerome Rothenberg suggested I develop the subject of hermaphroditism in my poetry into a totality — what he’s done with his poetry synthesizing Jewish tradition. I read several books on the hermaphrodite phenomenon. It is present in all cultures. Wherever people are, it is. Even so, the variability of its imagery begins to repeat itself. I could have drawn from alchemy and androgyny forever; but, I concluded, I would be writing the same poem over and over. Nothing wrong with Modigliani, but I’m the restless sort. Not since hermaphroditism, has any subject absorbed me more than pre-Columbian history. Started with sun carry-over from alchemy and ended with returning my heart to San Francisco.

Robert and Jess are of course poet Robert Duncan and his life-partner, the aforementioned artist Jess. When I first picked up A Lesbian Estate I felt immediately drawn to it by what I perceived as a correspondence between Lonidier’s and Duncan’s poetry. I soon discovered that indeed Lonidier enjoyed a decades-long friendship with the couple. The more I looked into it, the more I found endlessly fascinating how significant a figure Duncan is to Lonidier.

Reflecting upon Lonidier’s engagement with pre-Columbian Mexico, I recently noticed what I believe to be her presence in Jess’ major work, Narkissos. Over on the lower left-hand side of the massive paste-up ode to Eros appears a small drawing of a Mayan glyph. Jess worked on Narkissos from 1976–1991, and during the earlier years he arranged images on a pin board in the locations where they appear in the finished work. No source image for the Mayan glyph is on that board. I suspect he added it to the work after Lonidier’s trip to Mexico, a nod to their friendship. He may even have added it after Duncan’s passing in 1988, recalling Lonidier’s visits with him to see Duncan in the hospital during his final days. The tripe soup they delivered appears in Lonidier’s tribute to Duncan, “Doggerel for Duncan,” which she read at his public memorial.

Jess — brought tripe soup under hospital room’s hunkering TV set, and the nurse asks, “What’s tripe?” Jess — gentled appeals and Robert — endearing rumblings, they enduring describe jarred contents. The nurse is not sure she can intercom sustenance of the last batch of previous tripe. How so really Robert with tubes and bags and heating vats, so optimistically proceed in Time?

From P O T R E E (Berkeley Free Press, 1967).

Although she spent time outside of the city, Lonidier always thought of San Francisco as her home. She lived in the Mission and was an original founder of the Women’s Building; she also taught in local elementary schools. Included among her papers are several letters written by former students after her death, addressed to her brother Fred Lonidier, an artist, photographer, and UCSD faculty emeriti. Nearly all share remembrances of her dressing up for Halloween as either a Mexican wrestler or as Amelia Earhart (signs of a less culturally sensitive time — and maybe a fitting metaphor for her inner hermaphrodite?). Her energetic work imparts a sense of her enthusiasm for the amusing and colorful, as poet Jack Foley recalls: “Oh, the hats she wore!”

Yet Lonidier’s life ended in sorrow. Janine Canan, editor of Lonidier’s last book, The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariness, recounts in her introduction how after being laid off and bearing “the accumulated disappointments she had experienced in love as well as in work,” Lonidier fell into a deep depression. After her last hospitalization, she “was later found dead from an apparently intentional fall from a cliff onto a San Francisco beach.”

In Woman Explorer Lonidier asserts: “My ambition in life is to be a happy Hart Crane.” While she may have failed to realize that goal, her work, much like Crane’s, invites us to rediscover the world as she envisioned it, in language utterly her own. In her poem “Lesbian Heaven,” she rather jokingly envisions “All the girl friends you ever went with / are together now, and they’re all / getting along. They’re lovers of each other, / and you’re in the middle playing the lyre / with Greek attire.” It’s easy to imagine her there; happily surrounded, all there is to do, as she puts it, is “Pluck the chord, / pour the wine.” But would Lonidier want us to end on such an unambiguous note? Let’s also keep in mind the image of the poet in “For Sale: Girl Poet Cheap”: “O to be an Egyptologist with a child coming out my head with snakes inching my biceps and a beetle in my belly.”

In June, I’ll be presenting “‘O for some high blown language release’: Lynn Lonidier’s Robert Duncan” at the Duncan centennial conference in Paris. What I’ve shared here is an outgrowth of materials I gathered for the Duncan paper. The shards, as it were, that I was unable to squeeze in there. Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, edited by Julie R. Enszer, is expected from Nightboat Books in 2020.

Comments (2)

Totally wonderful, Patrick! And it should be mentioned that Rich Tagett is not only an admirer of Lynn’s work, but also published “A Lesbian Estate.”

Nice piece, Patrick! The Poetry Center’s 1965 recording, much from A Lesbian Estate (yet to appear) is here: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/poetrycenter/bundles/222886

A couple thousand listens, so somebody is out there.