Liberty and Luxury

Thus tangential subjects come into view. The thoughts, however, can, I believe, be traced to the event of a thread.

— Anni Albers

A few months ago, I wandered into Britex, San Francisco’s iconic cathedral of textiles. I’d never been to the new location on Post Street, and I gasped, mesmotized (as my mother would say) at the sight of the bolts of cotton, silk, wool, linen, fleece and fake fur, lace and satin, tartans, stripes, millesfleurs, and paisleys stacked from floor to ceiling, in every shade of every color.

Like a great library, bookstore, or formal garden, the place was tranquil yet buzzing with desire and possibility — Baudelaire’s luxe, calme et volupté.

An elegant man with a handlebar mustache was standing at the front of the store, folding yards of cashmere. He wore tailored pants, a vest, sparkling aquamarine stud earrings, and latex gloves. He welcomed me and asked how he could help.

I was too awed to talk. I’d once visited the old Britex location on Geary Street (easy to find because of the iconic red sign, which is still there). I’d spent a November afternoon in that tall, narrow building, haunting its four floors, learning about history and lace and suiting and tailoring from staff who seemed to have all the time in the world to share a wealth of practical and aesthetic knowledge.

This new store on Post is only two floors, but perhaps it’s even more inspiring because of the very high ceiling that reminds you this place is a kind of church, a pilgrimage, for many.

•

The man who greeted me is named Douglas, I now know; and no, he had not made his own clothes (I asked).

Was I looking for anything special, he wondered?

I glanced at the price tag for the ivory cashmere — $145.00 a yard — and felt the need to confess:

“I’m a writer . . .”

“Oh,” he said, “our store manager is a writer too.”

“And I don’t actually know how to sew . . .”

He smiled tolerantly.

“But I can hem and mend.”

“We have many visitors who don’t sew,” he said. “People who just come in to look or buy buttons or notions.”

Haltingly I tried to sketch out what I wanted to do: hang around the store, learn, write, and make art.

“Oh, that sounds like a great idea. Let me introduce you to our manager!”

Now, a few months later, I know that Douglas (like Ina and other staff members) has worked at Britex for years and has a loyal following among the store’s customers, and an archive of projects he has inspired and fostered for local clientele and visitors from all over the world.

And the gloves he had on that day? I’d worked in archives with rare books and fragile items, so I thought he was wearing them to protect the fabric. But now I know it’s the other way around: The sizing and other chemicals in textiles take a toll on the hands and cuticles. A hazard of the trade.

Standing in the middle of the store is like being in a Pantone womb. But I’m here for the language as well as the tactility and the eye candy. I ask questions, I eavesdrop. I look at the price and provenance tags tucked into the ends of bolts of fabric; I take pictures and scribble captions and vocabulary in my notebook.

“Sizing, “indigo,” “passementerie,” “selvedge,” “sharps.” This is what I want — to find the fossil poetry (Emerson’s phrase) in the language of textiles and, indeed, in things themselves. I’m fascinated by fabric and garments and their history (around the globe, and in my life) the way the poet James Schuyler loved (and wrote about) flowers though he was not a gardener.

•

“Galore,” an Irish word — more, more, more! — reminds me of ways to do more with less —

My mother’s mother, a Sicilian immigrant, went to work as a seamstress in a garment factory (a union shop) on Washington Street in Boston’s South End when my mother was six years old, and remained until she retired. She brought home piles of remnants from the fabric that they used to make uniforms for police and guards and firefighters — tough grays and browns and blues — and skeins of black thread as tough as twine.

For us, her grandchildren, she crocheted doll dresses as she had as a girl in Sicily (no child labor laws then and there), and made patchwork quilts from the uniform remnants and scraps of flowered cotton, polyester, and rayon.

Marjory Collins, Irish-American policeman in Central Park on Sunday, 1942. Courtesy Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2017836691/.

I didn’t like those quilts. I wanted something soft and pastel, less ethnic and makeshift. But now I find that my practice as a writer and collagist is not dissimilar to my grandmother’s as a cook, seamstress, maker of rag rugs: sampling and juxtaposition as commentary on the age of excess.

The cento, a poem made from lines taken from other writing (Yelp reviews of California prisons, for example, or knitting and sewing manuals), is my favorite form — a kind of quilt.

•

Last week on the ferry back to Oakland, passing the Port of Oakland and freighters stacked with shipping containers filled with goods from around the world, I wondered about that factory where my grandmother worked. By now most of those businesses are long gone — production off-shored — and so is that generation of Jewish, Sicilian, and other immigrants, the “garmentos” who owned the factories and worked in them.

At home, though, when I Google the name of the company where my grandmother worked, I find, incredibly, that it remains in business. Blauer, founded in 1936 by an immigrant from the Ukraine, still makes uniforms and tactical gear including bulletproof clothing. In this land where law enforcement and border control are growth industries, this “iconic provider of American military and special forces garments” is thriving. There’s even a fashion arm of the business now, designed for customers who want to look like militia.

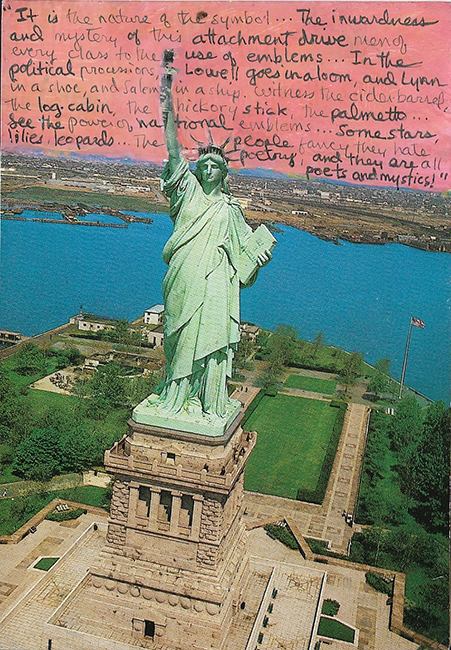

I still have an industrial-sized spool of khaki thread my grandmother got from that factory in the South End of Boston. I keep it next to my collection of pictures and replicas of the Statue of Liberty (I love its patina). That’s how I started out as a collagist when I worked on 42nd Street, doctoring cheap postcards of Liberty with Wite-Out and markers and photos from a pile at the flea market on the other side of the garment district.

Many of the most beautiful fabrics at Britex are designed and milled in Europe, particularly in Italy and France. According to a US State Department report about France’s textile production, other countries are far ahead in terms of technology, except for one of the leading new subsectors there: “Textiles with electronic devices and communication systems incorporated in the garments for either the security or sporting industries.”

•

What to wear to Britex on my first unofficial day of work as artist-writer-ethnographer-historian in residence? I put on my usual uniform: black cotton V-neck and leggings. But shouldn’t I wear something better today? There’s that Liberty of London print shirt in the bag of stuff to go to Goodwill. Re-re-cycled, since I bought it at Crossroads. It’s pretty but the neckline’s too low.

I try in on backwards. Perfect. Then I put on my black Isda jacket, bought on sale twenty years ago in New York, the nicest article of clothing I own, tailored in a black wool fabric so fine I can wash it by hand and hang dry it in an afternoon, no ironing necessary.

I wore it a few years ago to a panel discussion at CCA after Trump was elected. I made my way down the auditorium stairs after the presentation, passing Ishmael Reed as he talked with students. Without missing a beat, he glanced at me and said, gruffly, “Nice jacket.” Then he went back to talking about the 53% of white women who voted for Trump.

I bet they can find fabric like that for me at Britex. What would it cost, I wonder, to hire a seamstress and make a matching skirt at $125.00 or more a yard?

•

I am introduced to the staff at Britex, and almost to a person they comment on the fabric of my shirt:

“Is that Liberty?”

“Liberty?”

“Very nice Liberty!”

“Of London. Yes,” I say. (Fighting an urge to add, “But I’m no Anglophile, and I bought this second-hand.”)

Liberty print.

Founded by Polish immigrant Martin Spector and his wife Lucy in 1952, and now owned by their daughter Sharman Spector, Britex sells high-quality and luxury fabrics with an emphasis on fine European textiles. It is possible to believe that those who craft such things work in decent conditions — think “fair trade,” carefully sourced — unlike the majority of textile and garment workers in a world of fast fashion, planned obsolescence, and roving capital.

The story of textiles is the story of colonialism, capitalism, slavery and cotton, industry and invention, clock time and labor. Marx wrote about silk spun from the blood of little children working ten hours a day because the production of delicate fabric required delicate fingers. Now much of what we wear is made far away, in places with no child-labor laws, no unions.

Last week at the store I found a bolt of fabric reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty, a verdigris shot silk, sculptural when twisted. I also found an impossibly deep, fine indigo wool the color of water in New York harbor at night. And a bolt of sequined fabric, blue and green — that’s what Liberty would wear if she could escape from her pedestal and become a mermaid.

From these I can make a floor-to-ceiling quilt. For scraps of police uniforms, the rough blue stuff, I will have to look elsewhere.

Indigo has a cruel history as the first profitable crop harvested by enslaved people in the Carolinas. Blue-black indigo pigment, they say, has a lasting, fruity scent that is released when garments dyed with it are steamed or ironed. The Levi-Strauss company of San Francisco used indigo to dye its iconic American invention, blue jeans, made in the USA. These days blue jeans are milled and manufactured in maquiladoras and in Bangladesh, Vietnam, wherever labor is cheap, and organic pigments are rarely used in production. But there is a move to return to non-synthetic dyes instead of dyes derived from petroleum. Britex offers a range of beautiful denim printed in Japan, where there is a noble indigo tradition.

•

What about the bolts of fabric on the first floor at Britex, up near the ceiling, the ones that can be reached only on the upper rungs of the library ladders? What’s up there? Someone knows (which amazes me — how can the people who work here know so much?).

Does the staff need to visit the fabric up there to rotate the bolts or dust them every so often? I think of the farthest rafters of the great cathedrals, where workers carved lewd graffiti, knowing that pilgrims and priests would never see it.

•

The torsos and dressmakers’ dummies, the curves and drapery implicit in a bolt of fabric —arabesques of ribbon, rigor of zippers, folly of notions, and sample buttons like nipples stapled to small white boxes, inaccessible and tantalizing behind the counter —

And on the first floor, near the register, miniature pillows in every shade and type of velvet — plush pink, royal reds and blues and purples, toffee and butterscotch and chocolate — these you can touch — must touch.

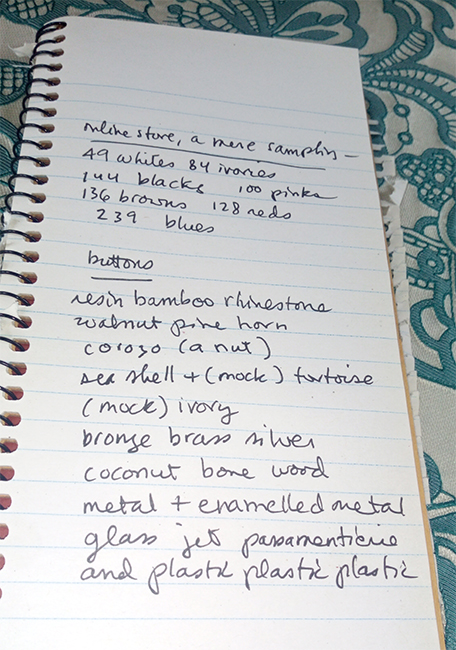

From the online store, just a small sampling of what’s available to bricks-and-mortar customers: 49 whites; 84 ivories; 144 blacks; 100 pinks; 136 browns; 128 reds; 239 blues. A list poem.

Buttons made of resin, bamboo, rhinestone, walnut, horn, corozo, (a nut), mother of pearl, mock tortoise, bronze, brass, silver, coconut, bone, wood, metal, glass, jet (a precursor to coal), mock ivory, and plastic, plastic, plastic.

•

At the front of the store on either side of the doors there are high-backed chairs for husbands. Not really, of course, but that’s who’s usually in them — men waiting while their companions shop for fabric.

At Britex, the people who’ve worked there for thirty years and the new staff are artists, ethicists, curators, merchants, and linguists selling in English, Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, Cantonese, French, and other languages.

Lance is an expert on couture and garment conservation and reconstruction. He says customers are surprised when they see him in jeans and flannel shirts, tattoos and boots and cap. He is an artist and couturier, went to Cooper Union and the Fashion Institute of Technology; knows the chemistry and structure of materials including old lace and satin; what fabric can do.

Dina, the store manager, demonstrates for me the sculptural properties of the dress she’s wearing. She tells me what happens to fabric when you put it in your mouth (saliva dissolves rayon, but strengthens linen). Says that if you’re cutting and sewing sequined fabric, be sure to wear goggles to protect your eyes. And never set polyester on fire.

Once, she says, a customer came into the store and asked for silk orgasma. You can see how that would happen here — this place inspires lust.

And Aleks — Aleks knows everything about upholstery fabric, and lots about lace. She simply won’t sell you black lace for a hem unless you bring the lace skirt you’re trying to lengthen. That wouldn’t be fair to you — or to the lace. There are hundreds of choices, a huge variety of blacks, whites, and ivories — sculptural lace, wiry lace, lace in dozens of patterns abstract or flowery, lace that stretches. Next time I’ll bring the skirt with me.

Sharman tells me about the challenges of selling the tactile in an increasingly digital world, and talks about slow fashion — a movement, like slow food? I think about how people in olden days used to have their dresses let out or taken in to accommodate pregnancy and weight loss or gain. Now, with spandex, our clothes have more give, and it’s cheaper to replace them than to take them to a tailor.

•

Directions on the San Francisco Zen Center’s web site for the making of rakusu: “These instructions are intended for those who have received permission from their teacher to sew Buddha’s Robe in preparation for a ceremony of receiving Bodhisattva Precepts, or for someone sewing a Robe as a gift for someone who has already received the Precepts. If you would like to sew but have not received permission, please discuss the matter with a Zen Center teacher.”

The materials and methods are strict and minimalist. I’m surprised when a friend tells me that some Zen teachers shop at Britex for the requisite (un-luxurious) fabrics.

Toward the end of her life, theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote about “making things, practicing emptiness”: sewing and weaving as relief from anxiety and craving.

•

Seamstresses and tailors, students and designers, legacy customers and first-timers and tourists come to Britex in search of textiles for Burning Man, the Renaissance Fair, the Dickens Fair, Halloween, Pride and drag, theatrical and dance productions, galas and home decorating, and, of course, weddings.

Behind the cash register, right near the little dog bed where you can find Kirby the pug, is the lace department. In this vast emporium of tweeds, wool, silk, cotton, and blends in every imaginable pattern and color, the vanishing point of all perspective is bridal lace, sometimes flowery, sometimes fragile to the nth degree; pure fantasy.

Since ancient Roman times, humans have printed textiles with vermicular (worm trail) patterns. You could think of worm trails as precursors to bridal lace.

On my way to this mecca for seamstresses and designers, I walk past human beings sprawled everywhere, hungry, begging, and I am careful to step around piles of human feces on the sidewalk. Nearby: Salesforce and Twitter headquarters, and “creatives” and “disrupters” who don’t let anything get in their way — the twenty-first-century Gold Rush.

And me, empapering what I see; anthropologist Michael Taussig considers writer-anthropologists (Jean Genet, Joan Didion, Walter Benjamin, W. G. Sebald) and their notebooks:

“There is something absurdly comforting in the existence of the trinity consisting of:

you

the event

the event notated as a notebook entry […]”

Writing as self-salvage, as mission: “Gather up the fragments that remain, that nothing be lost.”

Reading, looking, and writing as a way of having without spending: “Years ago I read about a pillar of roses in an English garden and so I own it, I have the deed by heart.” — Gertrude Jekyll

•

When I was a girl, stevedores still unloaded bundles and bales from ships as they had been doing since the dawn of exports and imports by sea and river. Now on the ferry from Oakland to San Francisco I watch cranes lifting containers from freighters (including the Thomas Jefferson, sailing under the Maltese flag) and stacking them in the Port. According to the UN, the shipping industry is responsible for about 3% of all the carbon emissions in the world. What will future generations make of our excesses of beauty and degradation? Will they read about us and find the stuff of our lives unbelievable, enviable and appalling? I write in my notebook: I swear I saw this.

Comments (9)

-

Barbara Falconer Newhall says:

February 22, 2024 at 10:29 am

-

Suzanne says:

January 5, 2020 at 11:28 am

-

Linda Norton says:

September 5, 2019 at 12:52 pm

-

Lynne Weiss says:

July 15, 2019 at 8:57 am

-

Linda Norton says:

June 1, 2019 at 1:35 pm

-

Constance James says:

May 31, 2019 at 1:39 pm

-

Amy-lynn says:

May 31, 2019 at 7:33 am

-

Jackson Braider says:

May 29, 2019 at 8:13 pm

-

Sue Moon says:

May 28, 2019 at 7:45 pm

See all responses (9)Britex! Wonderful store. Way back in the 1970s, I bought calico (I think it was calico) for a quilt to give my brother as a wedding present. I underestimated my skills and patience and 42 years later the quilt was still unfinished. With the help of a pro, my inept beginnings were turned into mini-quilts for the grandchildren who were now showing up in my brother’s and my life. It was Britex that made me want to make that quilt, and I treasure those vintage fabrics to this day. You can see them at:

https://barbarafalconernewhall.com/2015/02/05/the-quilt-from-hell-forty-two-years-later-its-still-not-finished/

Lovely piece, thank you

Sometimes I find an epigraph for a piece long after I’ve finished writing it. This is from Dick Lourie’s “Pinteleh Yid,” a poem about the bygone Jewish world of Clarksdale, Mississippi:

at its height it must have been like

the Lower East Side (one woman we’re told

would pull you into her store grab a dress

and hold it under your nose “This here is

imported” she’d say “can’t you smell the ocean?”

You have captured beautifully what I have sometimes felt on entering a really good yarn store. The colors and the textures! But you’ve added as well so much in the way of history, sociology, and back story. It did make me think of the old Windsor Button shop in downtown Boston where I used to like to browse (it closed a few years ago). I’m glad Britex still exists in San Francisco. But I wondered–I’ve sometimes had the experience of entering a store of beautiful things with a desire to buy and then left empty-handed because there was too much, and I realized that part of the beauty was the quantity and the arrangement. But at Windsor, I loved digging through piles of buttons and choosing one or two. Perhaps shops in which the goods are too well arranged end up doing themselves a disservice. (Doesn’t sound like Britex is one of them.)

Ride the ferry, visit Britex, and resist. Thanks for reading this piece and sharing this with others.

Linda, I LOVE this!!! In my mind’s eye, I saw the wonderful things you described. A fellow shop-owner friend and I used to take an annual trip to San Francisco in the Spring and Fall to get sweaters ideas. We always made a stop in Britex. I remember our drooling over the Liberty wool challis and then trying not to scream when we saw the $125/ yard price tag. You have made me put a trip to the “new” store on my bucket list. Thank you!!!

Beautiful piece, visceral. Some delicious words about amazing fabrics. Thank you!

What a whirligig of an entrance! “Empapering” — a short-term memory aid that is even less ephemeral than the paper it’s printed on. Great piece!

What a weaving of words and images. My mouth is watering—I’ll see what happens if I try to eat my rayon shirt.

I learned a lot, and now I can hardly wait to visit Britex. Thanks for empapering it for us.

Sue