Thinking with Strangers

I joined SFMOMA in early 2014, while we were “On The Go,” and although most of the conversations I had upon my arrival were, by necessity, about where we were going as an institution, I also wanted to understand as much as I could about where we had been. I read the official history in the 75th Anniversary catalogue, as well as the transcripts of the SFMOMA Oral History Project, and spent time in the archives, looking for traces — for micro-histories within the museum itself — that could be reanimated and questioned as we looked toward our next incarnation. I was in search of inspiration, too, for the work I was now supposed to do under the rubric of “Public Dialogue”: commissioning participatory forms of public engagement that are discursive, durational, and that reach beyond art and beyond the institution, enabling a dialogue about the role of the arts in the fabric of civic life.

I conceive of this work as creating opportunities for thinking together with friends and with strangers, after Michael Warner’s idea of a public as a convening of strangers and William Isaacs’ idea of dialogue as the art of thinking together. It is also a process of connecting dots. I work with artists whose practice involves archival and/or collaborative research with publics, as well as those whose work creates space for multiple perspectives. Very often our collaborations combine these approaches, and explore the constituting of collective histories as a form of community dialogue. This involves listening, raising questions, looking for affinities, and identifying tensions. Often the ultimate topic is memory: its retrieval, presentation, and activation in this place at this time.

Having spent the previous five years working outside the US with non-Western artists, largely for a new institution that aimed to reincorporate the history of modern and contemporary art of the Arab world into wider art historical narratives, I arrived at SFMOMA looking for evidence of the ways in which the museum has involved underrepresented communities, both artists and publics, especially those of color. How had it approached questions of difference, of inclusion, and how and when did it seek to expand representation, at different moments in time? When did it escape its own official narratives about itself? I was also curious about its broader reach. When an institution is primarily about preservation, what is its role in social change?

What legacy can we choose to inherit, and what legacy do we want to leave behind?

—Gray Brechin, geographer and author of Imperial San Francisco

From my early reading I learn how SFMOMA’s founding director Grace McCann Morley kept the museum (then the San Francisco Museum of Art, SFMA) open late in the 1930s for the working people of San Francisco, about her productive friendship with Diego Rivera and her work with the burgeoning UNESCO. Digging further I learn she championed underrepresented artists in the 1940s and 1950s, including women artists, as well as those from marginalized backgrounds in the United States. I learn about her presentations of solo shows of artists from overseas, especially Latin America, but even Iraq (the first solo exhibition of an Iraqi artist in the US is likely Madiha Umar’s solo exhibition at SFMA in 1950). Morley supported and promoted local women artists of color, such as Thelma Johnson Streat and Mine Okubo, as part of her larger mission to expand the reach of the museum as much as possible, even as she brought the most prestigious names in modern art to San Francisco from across the country and around the world. In conversation with national thought leaders as well as local architects, designers, artists, and thinkers, Morley encouraged a public dialogue around art — not just about the museum’s contents, but also involving activity beyond its walls.

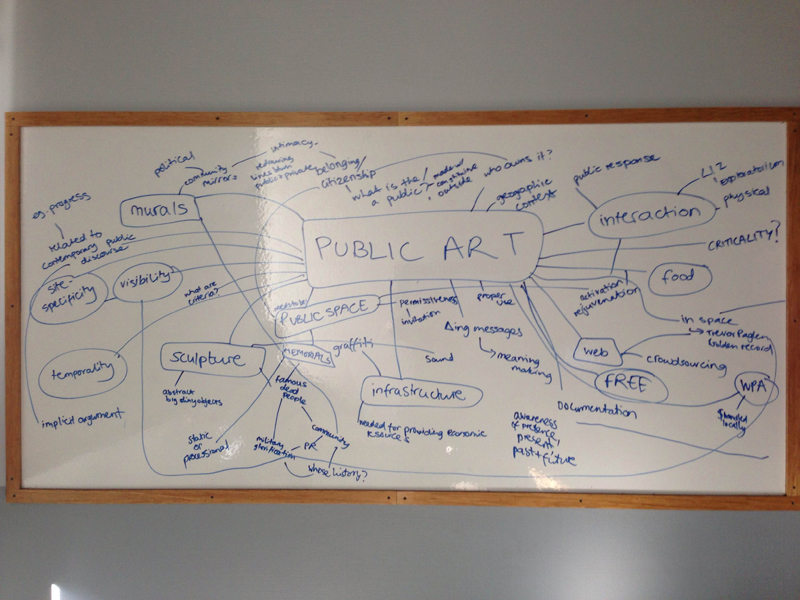

I looked for allies and collaborators interested in supporting an investigation into some related aspects of this legacy: the early years of San Francisco’s arts infrastructure, what public art has meant in SF and how it has been read and might be read today. I chose the Rincon Center as one of the sites to explore, given that its main mural by Anton Refregier contains an important if contested history of the city as well as a connection back to the museum.

Amanda Eicher developed Can We Talk About Art, a unique project designed to galvanize communities and conversation, while geographer Gray Brechin, art historian Berit Potter, cultural journalist Caille Millner and local historian Chris Carlsson shared local stories reflected in the artwork that still resonate today.

Refregier had won a commission organized by the Federal Art Project in the late 1940s to create a mural about “The History of California” for the post office on Spear Street near the Embarcadero. The twenty-seven-panel mural was completed in 1949, and emphasized labor struggles as well as the role of ethnic groups (Native Americans, Chinese Americans) often written out of official early narratives; it culminated in the signing of the UN Charter in San Francisco in 1945 (an historic moment now often forgotten).

In 1953, Congressmen in the House Committee of Public Works looked to destroy the murals on the grounds they were “designed to slander the state’s pioneers and convert patrons at San Francisco’s main post office to communism.” The SFMOMA archives contain the numerous letters that Grace McCann Morley wrote in passionate defense of the murals and Refregier. Morley went further, organizing a committee to protect them, and championing the value of public art and free expression, locally and nationally.

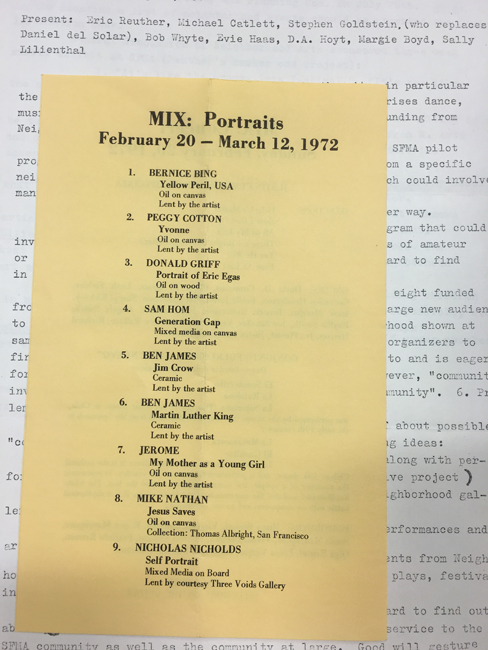

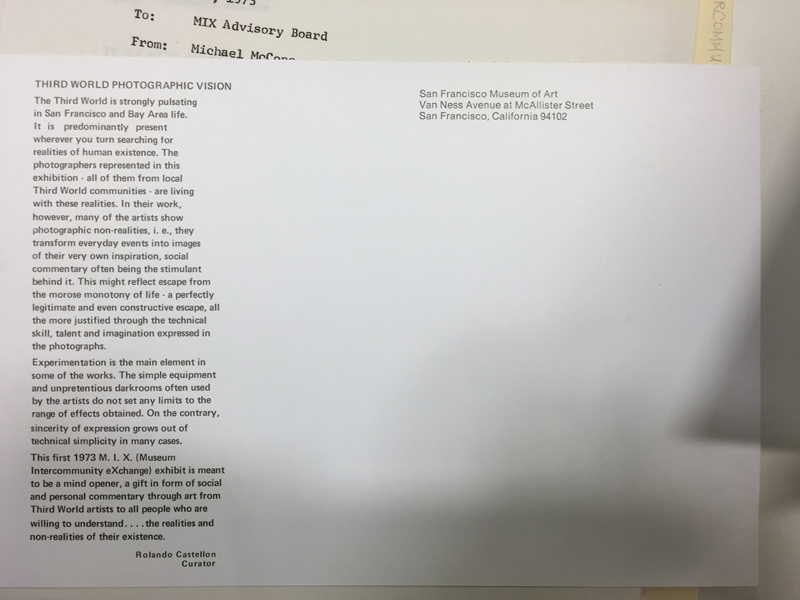

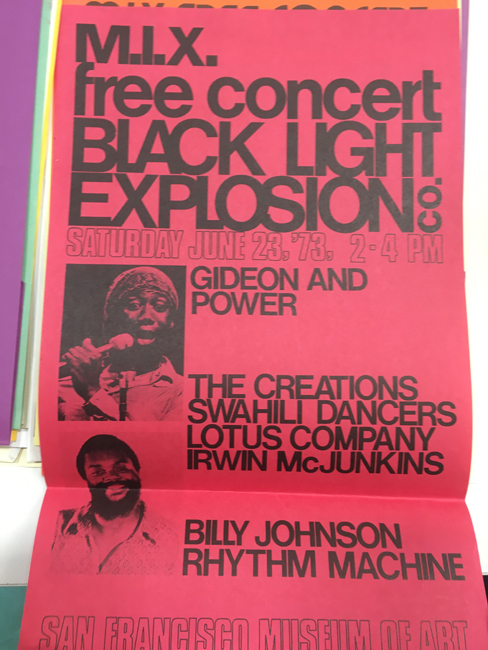

1972: SFMA establishes the Museum Intercommunity Exchange (MIX) to engage a broader cross-section of the cultures of San Francisco and expand the museum’s audience. Rolando Castellón signs on as program coordinator of MIX and produces exhibitions and events such as free concerts and dance performances.

•

1976: Castellón brings attention to the tradition of outdoor murals in the Bay Area, particularly in San Francisco’s Mission district, with the exhibition People’s Murals: Some Events in History (July 8–August 8). The museum commissions eight portable, large-scale murals with political themes such as “The Struggle of Native People for Sovereignty” and “Low-Income Housing.” After the show, the murals circulate to community organizations.

—from the Chronology in SFMOMA’s 75th Anniversary catalogue

I go back to the archives to understand more about Museum Intercommunity Exchange, since it seems in some ways to be a precursor to the kind of work my department does today. The name strikes me as awkward, temporally foreign. I find early letters establishing the program, posters of early public concerts, grant reports detailing a range of exhibitions, symposia and lectures in addition to the performances described in the official chronology.

Originally from Nicaragua and now living in Costa Rica, Castellón found himself referred to as SFMOMA’s “Third World” curator. He organized a series of exhibitions at SFMOMA around the rubric of the “Third World,” each based on a different medium, all featuring Bay Area artists of color. The stakes of wider liberation struggles were brought to bear on the museum, with the goal of visibility and representation. A photography exhibition traveled to the recently founded Kearny St. Workshop in Chinatown and then to the Bayview branch of the SFPL. The painting and sculpture show included Robert Colescott (although it would be longer before Colescott’s work entered the collection), Manuel Neri, and Carlos Villa. There are photographs from the exhibitions that present a diverse San Francisco but at his request there are no photographs that officially depict Castellón. Press coverage in the archive for several shows is positive, if bemused.

An artist himself, Castellón lived in San Francisco for decades and in the early 1970s was one of the co-founders of Galería de la Raza, the Mission-based organization devoted to Chicano and Latino art with which my department at SFMOMA has partnered several times in the last few years. The current exhibition in the Koret Education Center, Remezcla Graphica/Graphic Remix, is one of the latest collaborations.

While I am researching the relationship between the organizations for the exhibition with Dominic Willsdon and Ani Rivera, we come across pamphlets and posters of exhibitions from 1972, when works from the SFMOMA collection by Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozsco were shown at Galería. Photographs in the SFMOMA archive show members of Galería reviewing the museum’s Latin American collection.

Despite these early connections, I find little else that explores the museum’s relationship over time to artistic communities of color in the Bay Area. As I look further afield, thinking about how knowledge is produced and how history is written, I am interested to learn about (and sorry to have missed) an exhibition at the Luggage Store curated by artist Carlos Villa in 2010 that represented a concerted effort to incorporate women artists and artists of color in the local history of abstract expressionism. As far as I could tell, SFMOMA was not involved.

Shared a feeling with my people. Looked into their faces and saw mine. Language was not a barrier. Each smile warmly communicated, welcome home my brother, welcome home my sister, welcome home.

—Lige Dailey

My first large-scale project at SFMOMA piloted our ongoing partnership with the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) and highlighted its role as an accessible archive, a community resource, and a space for critical intervention. Chimurenga Library was a multi-faceted research project and installation conceived by the collective Chimurenga from Cape Town, South Africa. Described by the collective as “an exploded history book,” the installation comprised multimedia elements over several floors of the SFPL Main Library branch at Civic Center, creating thematic pathways through the library’s content. The project’s subject was FESTAC ’77, a massive, largely forgotten pan-African cultural festival that took place in Nigeria in 1977 and included participants from all over the world in a month-long program consisting of dance and music performances, a visual art exhibition and a heavy-hitting conference with leading intellectuals.

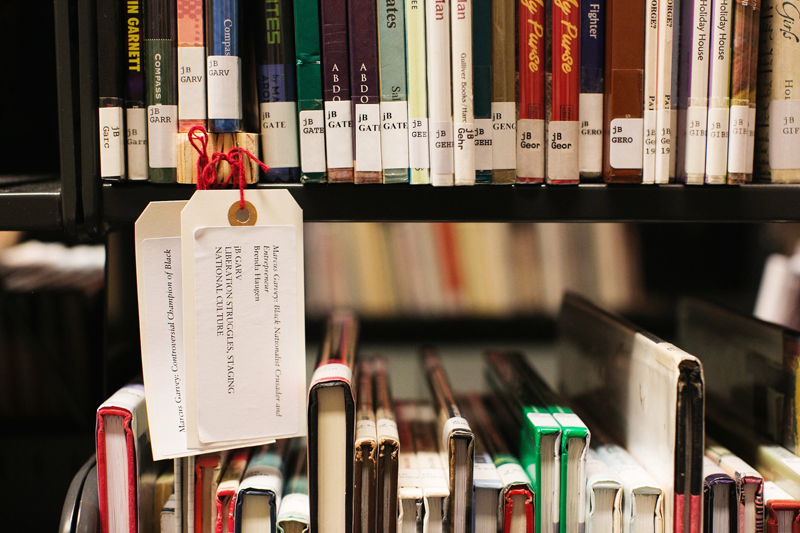

Through keywords associated with festival themes (liberation struggles, the post-colony, music), and participants (Louis Farrakhan, Miriam Makeba, Stevie Wonder, Audre Lorde, Wole Soyinka), the installation explored the ideas animating pan-Africanism from the 1970s to the present, as well as the role of the African diaspora in the Bay Area, both historically and in the present. Chimurenga’s stated goal for audiences was “to find ourselves on the shelves.” Thanks to an intrepid team of local researchers working alongside the collective, we discovered 600 keyword-related items in the SFPL collection, including books, periodicals, posters, and music.

We discovered in the SFPL special collections, for example, that many of the important pan-African literary magazines of the 1960s and 1970s had been published in the Bay Area: Soulbook, Kitabu Cha Jua, Black Dialogue, Journal of Black Poetry, Hambone. Only Hambone is still published today, albeit as a different journal. We learned that several artists in the SFMOMA collection had exhibited work at FESTAC, including Mel Edwards and Robert Colescott. Late in the research we also learned that 400 Bay Area residents had attended FESTAC as performers and participants, and I knew immediately how much richer the project would have been had we found them at the beginning.

With limited time I was able to track down only a few local FESTAC participants, but I invited those who expressed interest to participate in the public program at SFPL to launch Chimurenga Library. Dr. Lige Dailey, a psychologist from Alameda, described his experience attending FESTAC with Albert Walker as the Soledad Prison Poets. The festival changed the course of his life, and this was the message we heard from everyone from who attended, as well as the message we gleaned from several biographies.

The Chimurenga Library project had asked an important question: how could a cultural event so large in scale and reach as FESTAC ’77 have such a small place in history and in broad popular consciousness? The answer, it turns out, is because it didn’t register in the wider (white) cultural sphere at the time or afterwards. As Alexis De Veaux puts it: “Only a handful of the black Americans who went to FESTAC ’77 wrote about what it was like to be there, and most of those were affiliated with the black press. Much of the white American press ignored FESTAC. None of the black American writers published a major piece on the events in Nigeria, despite the fact that FESTAC was life-altering and shaped lasting personal and artistic bonds between artists who participated in it. Its magnitude became nearly impossible to delineate beyond themselves.”

It is deeply unfortunate that the historic lack of visibility for African diasporic culture nationally is still reflected in the contemporary local African-American experience. During a recent SFMOMA On The Go exhibition collaboration with MoAD, my MoAD colleague Elizabeth Gessel and I invited the 3.9 Collective to organize a series of gallery talks by local artists reflecting on works by artists of the African diaspora. Unsurprisingly, many of those discussions turned to forgotten histories of San Francisco neighborhoods and communities. In front of a David Huffman “traumanaut” painting, for example, Rodney Ewing discussed the concept of home and his current work on the history of cultural disappearance in the Fillmore.

The changing demographics of San Francisco and its increasing levels of inequality continue to provide a challenging context within which to talk about identity and representation, whether of Bay Area residents, communities, institutions, or of individuals. I intend to create projects with an emphasis on political and cultural engagement, to provide resources for audiences to ask questions about representation. Through the archive I’ve seen glimpses of different ways in which similar questions have animated the institution at different moments in its history. There are rarely fully satisfying answers.

Knowledge can be public, but undiscovered, if independently created fragments are logically related but never retrieved, brought together and interpreted.

So far each project I’ve embarked on at SFMOMA has assembled fragments from our archive and others’, opening up windows into micro-histories and communities. I question what it means to peer through them from where I’m standing. I make endless lists of things to read, to follow up on; even longer lists of people to meet for the first time. People to meet again; to follow up with.

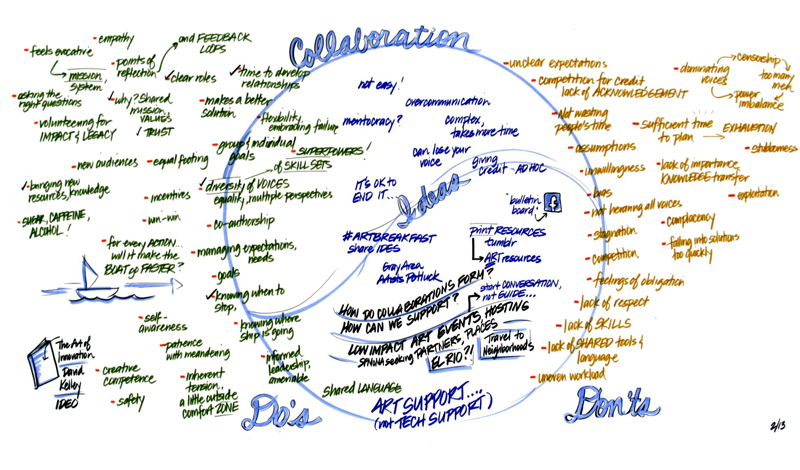

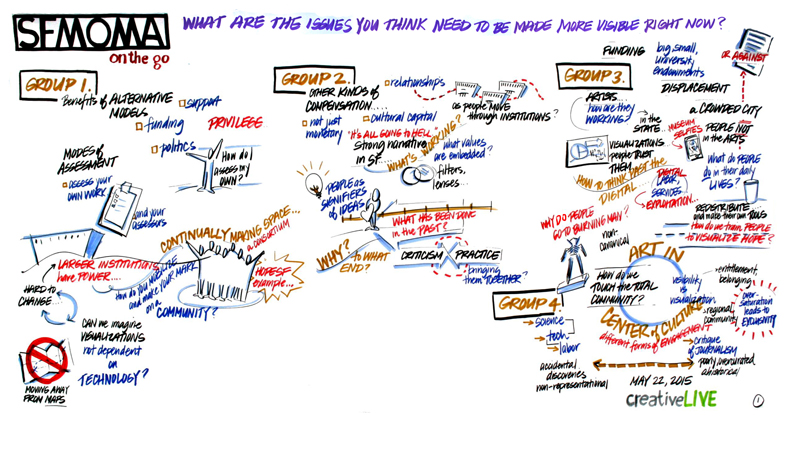

I work best with those who are invested in having intergenerational conversations, finding intercultural resonances, fusing disciplinary approaches, and I collect names of those who do the same. In the spring of 2015 we began convening a series of what we called creative research workshops to connect them to one another, collaborating with such organizations as Gray Area Foundation for the Arts, KQED, Creative Live, and SPUR as an experiment in collective thinking and relationship building. We invited local artists, writers, cultural historians, community activists, librarians, and researchers from many disciplines to exchange knowledge, skills, and perspectives around different themes, like “Reskilling,” “Resilience,” “Storytelling,” and “Visibility.” Each discussion was an opportunity to listen to one another, to learn about everyone’s practice and ideas, and to think critically about the museum’s role in the cultural landscape and how we might best share its resources. In essence, by bringing internal aspects of the museum outwards, and inviting external partners in, the goal was to ask ourselves: what do our efforts make possible and for whom? What kind of change would we like to see? And how do we work together? Conversations were often (inevitably) uncomfortable but invariably revealing.

I tried (and failed) to model what the legendary Berkeley publisher Malcolm Margolin has called “the art of deep hanging out”: spending time with others without agenda, just talking and listening and learning about “the fullness of each others’ lives.” For most of us it is hard to create that space, but Margolin made it a critical part of his work. Since he published East Bay Out in 1974, he has built a tight-knit community around his publishing house Heyday that focuses on hidden histories of California, in particular its Native American history and present.

From Morley and from Margolin, I imagine SFMOMA as well as the Bay Area at large as a palimpsest of cultural actions and at the same time as an ecology: a series of networks of people and ideas, continuously morphing over time and folding back on themselves. I begin to wonder whether everything will tie into everything else if we look for long enough.