Chasing Medusa’s Ghosts

The music I make now has become a platform for my rituals, for exorcising the lurking shadows of Medusa. The tears…

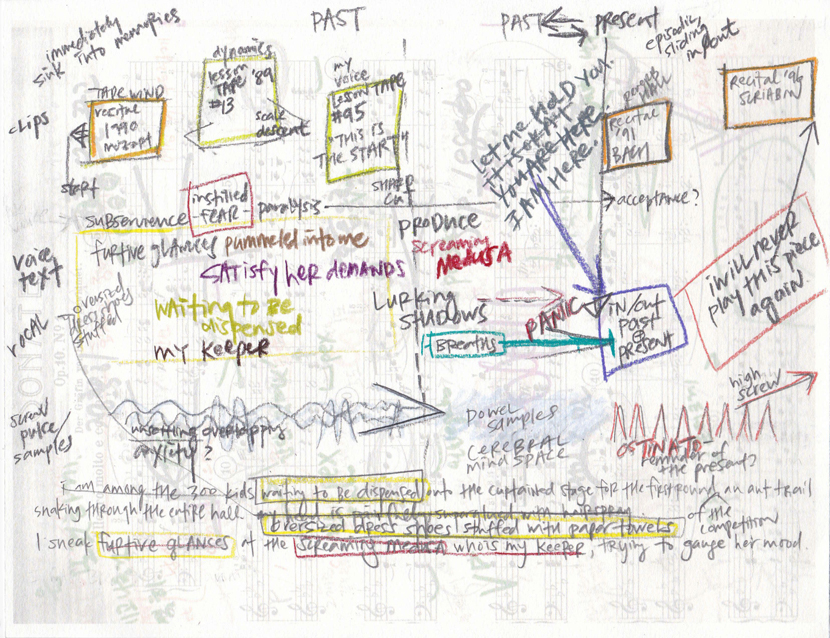

I am among the 300 kids waiting to be dispensed onto the curtained stage for the first round of the competition, part of an ant trail snaking down the long hall. I’m wearing headphones with a cassette recording, custom-made the night before with last-minute advisories dubbed over my best take. My head is painfully superglued with hairspray and I’m wearing my father’s ski gloves; I double-up with the hot pack between my six-year-old palms and scrunch my toes in their oversized dress shoes stuffed with paper towels. For the next four-and-a-half hours, the same sonatina will be churned out, and I bask in the comfort of one single thought: I will never play this piece again.

Nine-hour shifts in a Plexiglas chamber with an upright piano (and a fifteen-minute food break). I’m showing my fellow cellmate, Bach, the Baroque articulation pummeled into me over the weekend, while Chopin and Liszt play gin in the corner. A paperback is tucked between my legs and I sneak furtive glances at the screaming Medusa who is my keeper, trying to gauge her mood to prepare myself for tonight’s offering. According to her usual insults, I am later to become an invalid, along with parts of female and male genitalia, but escape the death threat by a hair.

도리도리, 도리도리! 1

This was why I live and this was how I died.

Naturally, I quit. I decided to become a computer programmer, then a psychologist (of course, I could treat myself); it didn’t work out. It took me a decade or so to embrace music-making again, to begin to believe I could have it on my own terms. This work, of believing, continues today.

My life as an artist is not a glamorous life, not a bigger one, but deeper. I have a voice.

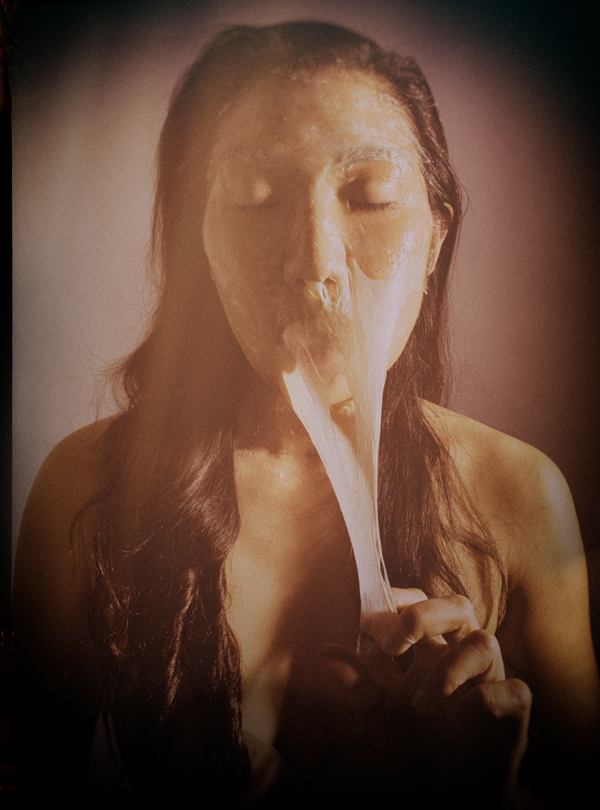

The music I make now has become a platform for my rituals, for exorcising the lurking shadows of Medusa. The tears…

With each performance and work, with each student I bring my heart to, the tape gets a little older and less relevant, and this is how I step into my present.

Armed with hot packs and extra layers, I clumsily maneuver an eighty-pound keyboard between alleys to prepare for a different kind of concert, deliriously happy to have traveled across oceans to lug a keyboard onto the streets so I could play my music in the numbing winter cold, stripped of the amenities: venue, piano, electricity, audience. The sense of whom this is all for shifts in front of me.

I move through the constellation of gatherers. My last utterance — “I am here” — has never been above a whisper in concert halls. But on this night, over the din of traffic and street noise, the words come out of me bellowing at the buildings and Korean skies. It is January 2015, and I am standing on the streets of Gwangju with two Korean-American colleagues from Mills College. I have come full circle back to this country: as a girl I lost myself among the concert halls with assigned seating, everything perfectly in order. Now I find myself in the amazing disarray of noisy cars and street lights. I am fueled by… what? Certitude? Power? Strength? Something I can’t describe.

Medusa had it wrong. I occasionally extend an invitation to take her to tea and listen to what she has to say. Her story is tragic, it’s compelling. I lock the door behind her.

•

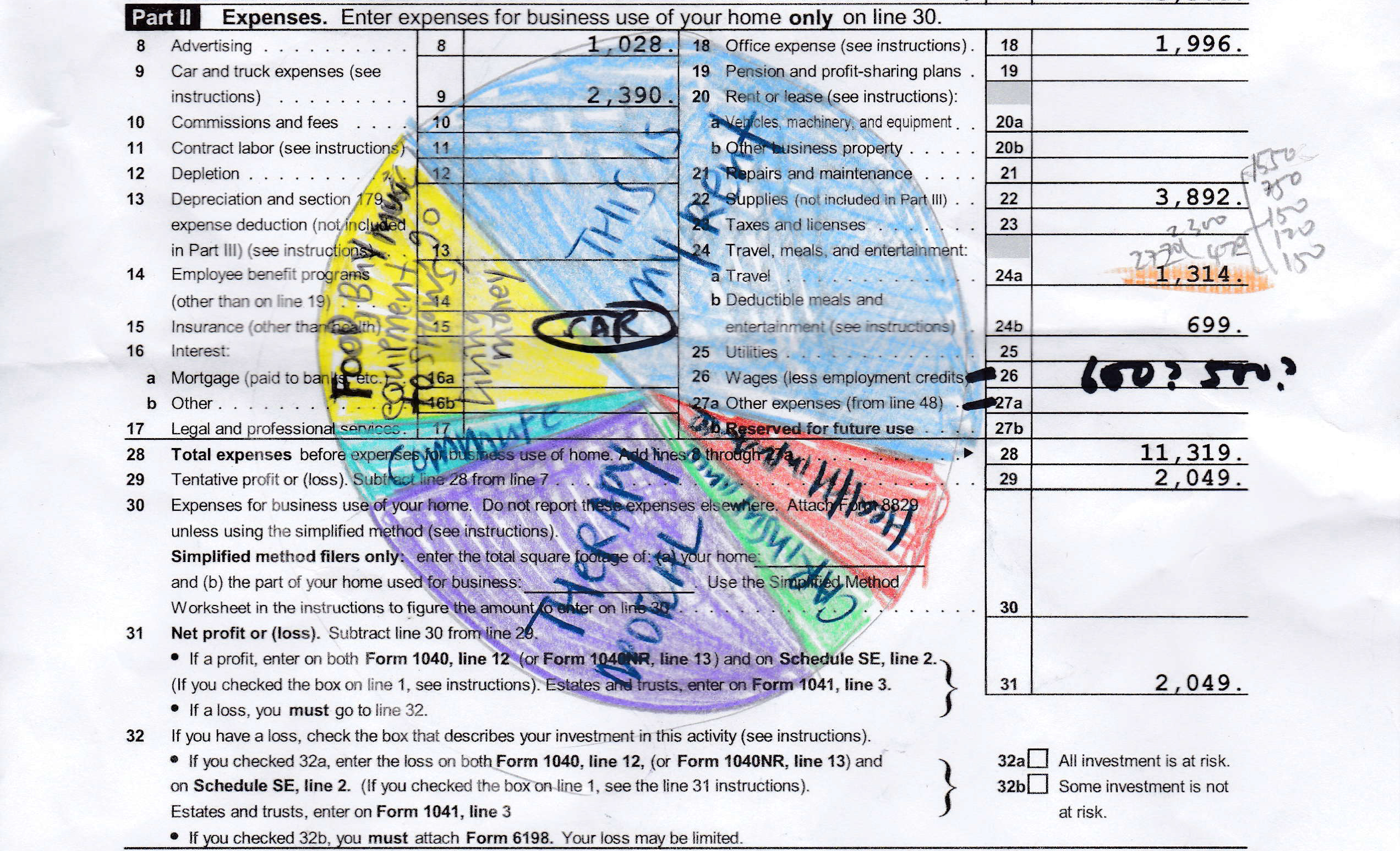

I see my forty students over the course of my week, sell a piano or two, devote my energy to recovering and healing, make music with the members of my community, scurry to work on my own music, squeeze in performances wherever I can, pay my bills and keep that appointment with the dentist, take that extra moment or two to appreciate the life I get to live as a freer woman. The hustle is often exhausting, the financial security vague at best, the career path unknown.

If I don’t work, I don’t get paid. In the world as a piano teacher, I don’t have sick pay or health benefits — my job goes unprotected. I can’t tell the three-year-old kid for whom that honeymoon period of initial interest in piano has ended that my rent hangs in the balance. Somewhere out there, there are (and I must find) other parents who will pay for their child to have piano lessons.

The majority of my skill set lies with this immobile instrument. I am completely dependent on any given venue at hand for its condition, maintenance, and tuning — never mind its actual existence. This is a one-night-stand venture most of the time — hello and nice to meet you, I’ll take whatever I can get. Pianists need not only make time to practice, but also find a place to practice. We are constantly on the prowl for places with a lonesome piano, becoming proficient in asking (begging) nicely and bribing with pastries (recently, I adopted a throwaway piano and paid more to mend its broken keys than to move it).

I’d like to think my music-making could someday be a business, that is, an entity I could consider in terms of monetary profit and financial sustenance. At this moment, it remains in a would be nice stage, shelved among things like owning a home or the Steinway with that pearly touch.

Perhaps I will someday consider matters differently (maybe when I get that Steinway). Perhaps I’ll look in the mirror and see a glorified piano teacher wasting herself to teach this five-year-old the complications of a dotted eighth note; I’ll take insult at a performance where the audience consists only in the other performers on the bill and decide something’s got to change. Perhaps then I’ll go back to school and spend (in loans) another two hundred thousand on an education (or better yet, say the three letters that will answer my family’s prayers for my chance at a successful life). But for now, I get to live this life. I get to somewhat afford to live in a community where I can learn to exist as myself. I get to do this:

Photo credit: Ian Montgomery

Comments (1)

You go girl! Chase your dreams 🎹