From Digital to Dust

Kanye West, “Through the Wire”, from The College Dropout (2003).

There’s no accounting for the habits of the collector. Some spend their lives focused on a single niche, others hop around specialties and formats, playing hopscotch with the cultural artifacts that define their obsessions and fill their apartments. As a lifelong collector of recorded music I find myself broadening my focus with each passing decade. The defining objects from the past I once took for granted start to disappear from the landscape and I get the compulsion to start accumulating with a more specific purpose. In the mid-’90s I chased down the vinyl LPs that had been ubiquitous in my early youth but were actively being phased out by record labels; in the ’00s I moved on to cassette tapes at a time when everyone but truck drivers and inmates had given up on them.

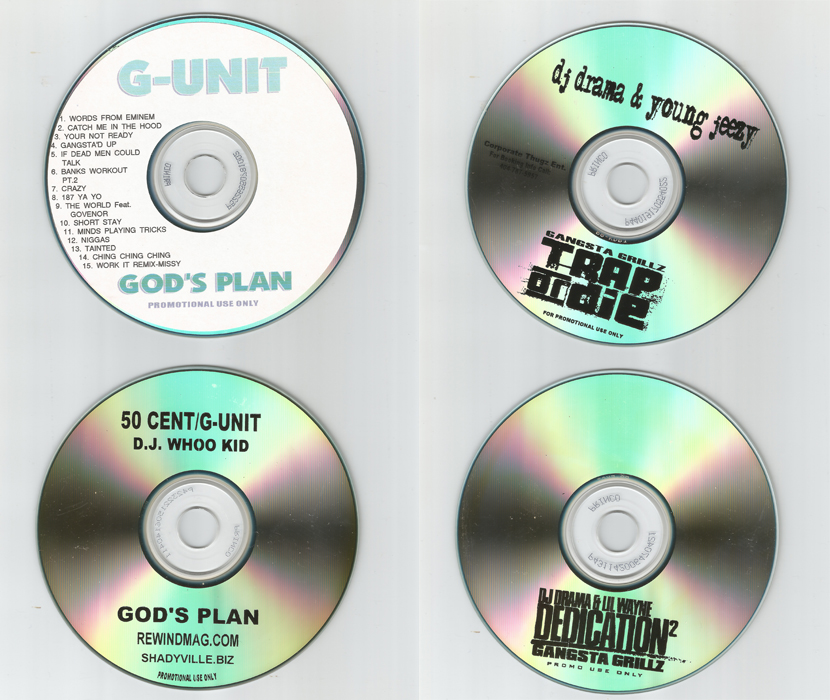

Lately (and predictably), my interests have shifted once again, this time to a particularly volatile format: the CD-R mixtape. (The name is a confusing holdover from the cassette era — by the turn of the century mixtapes were rarely tapes and only occasionally mixed.) For in-the-know rap listeners these releases were the essential medium at the turn of the century — low-budget products on the grey market these underground albums were sold at flea markets, gas stations, or on street corners, and were comprised of non-album tracks and loose freestyles to other artist’s hits. Many formative works by the most important rappers of this era — Lil Wayne, 50 Cent, Kanye West, Gucci Mane, Cam’ron, Young Jeezy — only ever saw release via mixtapes. And while these projects were usually uploaded simultaneously to online archives like Dat Piff and, later, Live Mixtapes, many of those uploads were shoddily compressed mp3s with awkward gaps between tracks. Today loose tracks or even entire tapes have been lost to copyright claims from a confused record industry that was never quite sure of how to handle the format. (This is to say nothing of the thousands of possibly-great-but-probably-not CD-Rs produced by lesser known artists that never hit these sites at all, many of which are now likely completely lost to time.)

Excerpt from The Diplomats’ Diplomats Volume 4 (2003).

Sometimes these mixes were manufactured in small promotional quantities by the artists, labels or DJs themselves. More often they were burnt off by a third party, sometimes from high-quality official masters, sometimes from a download of ill-repute by a teenager in his bedroom. In the moment I never got too caught up in the physicality of these mixtapes. The digital age was upon us and I was computer-savvy enough to have most of the tapes before the street vendors. And besides why would I pay $5 for a copy someone else burned when I can burn it off myself? This was fair reasoning in the moment, but a few years ago my impulse as a collector who lives to own and owns to live kicked in, and I began to try and track down copies of all the classic CD-Rs that I never bothered to buy or burn in the first place. It is the music of my youth and if I can just hold it in my hands — the way we used to hold music in our hands, dammit — surely it will help slow the aging process. So here I am, once again mining flea markets and eBay auctions for yesterday’s garbage.

In true music collector fashion I’ve been prioritizing original pressings in my search for this garbage. Since there is no guidebook or Antique Roadshow for these things, I’ve invented my own half-baked verification standards — gauging the quality of the front insert’s card stock or the print on the disc itself, checking for the presence of a manager’s contact information or an official endorsement from a record label or clothing line — but it’s all proven mostly pointless. The sonic and physical differences between a sanctioned release and the bootleg of a bootleg is almost completely imperceptible to humans. Maybe 50 Cent’s in-house DJ really did print up the insert to his seminal 50 Cent Is The Future tape on an inkjet printer. (It’s billed as a “Collector’s Edition”, after all.) And maybe he didn’t. Either way, perceived authenticity rarely has any bearing on the actual sound quality usually close to horrible to begin with.

Worse still there’s an increasingly high likelihood that a CD-R from this era will simply not play. While LPs and even cassettes will last for decades if properly taken care of, CD-Rs often begin to degrade in just a matter of years and there is nothing you can do about it. (When the format was launched manufacturers boasted of lifespans of up to 100 years.) Sometimes you can see the telltale speckling of tiny needlepoint holes on the back of a dead CD-R, other times the disc’s failure only becomes apparent when the audio fills up with clipping and crackling white noise or your CD player starts to whir and sputter. Frequently only the first few tracks are playable. Many CD players will refuse the disc entirely. Sometimes a disc that didn’t work yesterday might play fine tomorrow. The worst of them have been reduced to sheets of raw digital noise. I’d estimate about one in three of the CD-Rs I find from the early to mid-’00s — even the most official-looking ones — is functionally damaged in some fashion, and I assume that the rest have already begun to decay in ways my ears can’t yet comprehend. My best option is to rip some janky distorted mp3s (if possible), then file away a dead or dying disc as a symbolic placeholder on my CD racks. Realistically, I’m just going to just hit Dat Piff the next time I choose to listen to the tape anyway.

Young Jeezy, “Intro”, from Trap or Die (2005).

And yet there’s something almost freeing in knowing definitively that the objects I’m chasing are probably fake and certainly destined to self-destruct. As a format the CD-R relieves the collector of our two most cherished rituals – authentication and preservation. These are the acts that give collectibles their value, be that monetary or the less easily quantifiable “historical” value, and which by extension lend a sort of implied nobility to our compulsions. Theoretically those valuations are what separate us from mere hoarders and pack rats. The decaying CD-R leaves all the cracks in this facade. Infinitely duplicable but rapidly decaying, they demand the presence of an active archivist who can continually daisy chain back-up hard drives or stack clouds on top of clouds. And one day that collector will die, and without a worthy successor so goes their precious archive. Of course this always has been true of media, from vinyl LPs to stone tablets. Permanence is an illusion, ownership is temporary.

Comments (4)

P.S. I always liked the disclaimers or randon notes on the covers like “FEE BANKS FUCK YOU PAY ME” in the format of the parental advisory warning label or “DO NOT SPEND A DAMN DIME ON THIS!!! I’M GIVING IT TO YOU FREE!!!” on the covers of LIl wayne mixtapes.

I have a tablet and flash drive full of mixtapes I downloaded off of Datpiff and Livemixtapes. However, I always end up listening to CDs. If I want I want to find something to listen to, I always go to my CDs. Therefore, I always buy physical copies of mixtapes if I can. To be honest, I haven’t even listened to a lot of mixtapes I’ve downloaded. It is nice to know that some did support the artist/dj etc.

I guess it is the lack of the preservation ritual that you mentioned. It never feels complete just downloading music.

But I was late to the game of buying the physical mixtapes. I started off with the lil wayne mixtapes back when Amoeba’s Lil Wayne section was always overflowing with his mixtapes. I got the Dedication 2, Da Drought 3, Carter 3 mixtape, Best Rapper Alive 4, Lil Weezy Ana Volume 1, and Before the Carter to name a few.

Great, great read on an object that became a culture that you truly had to be there to experience.

i cherish my circa 2002 cd-r’s i burned of the random albums i checked out at the library that were scratched to shit