José Esteban Muñoz, in Memory and Futurity

On December 26, 2013, D-L Alvarez sat down with theater maker Jorge Ignacio Cortiñas to talk about the death and lasting influence of noted critic José Esteban Muñoz (1967–2013).

D-L: I’m not sure I can conjure up my first meeting with José. It must have been in 1996, and Nao Bustamante would have handled introductions. Was it in a gallery? Probably, though when I picture it, I see it in his apartment, which was always the place we would later go to recharge our batteries, after an opening or performance but before the after-party: him, Nao, and I. It was central, and that was a fitting metaphor for José as well, his position in the midst of various art world crossroads. He was supportive of my work from the get go, and I’ve come to understand this was also typical. If José liked what you were doing, he had confidence in your undertakings, often even before you did. My first university gig was speaking to his class on performance art. At the time I felt undeserving, like a snake oil peddler trying to pass, but he invested so much belief in what I was doing that I started seeing my work through his eyes, which was a much better view.

On December 26, 2013, D-L Alvarez sat down with theater maker Jorge Ignacio Cortiñas to talk about the death and lasting influence of noted critic José Esteban Muñoz (1967–2013). They met at D-L’s studio at the ISCP in Brooklyn. For links to bios for most of the people mentioned in this conversation, scroll to the bottom of the page.

D-L: I’m not sure I can conjure up my first meeting with José. It must have been in 1996, and Nao Bustamante would have handled introductions. Was it in a gallery? Probably, though when I picture it, I see it in his apartment, which was always the place we would later go to recharge our batteries, after an opening or performance but before the after-party: him, Nao, and I. It was central, and that was a fitting metaphor for José as well, his position in the midst of various art world crossroads. He was supportive of my work from the get go, and I’ve come to understand this was also typical. If José liked what you were doing, he had confidence in your undertakings, often even before you did. My first university gig was speaking to his class on performance art. At the time I felt undeserving, like a snake oil peddler trying to pass, but he invested so much belief in what I was doing that I started seeing my work through his eyes, which was a much better view.

Jorge: I met him at a queer CUNY conference in the mid ′90s, I think. I delivered the sort of polemic I was prone to at that age. (Robert Vazquez said listening to me deliver that speech was like listening to a machine gun.) When I was done, José came up and introduced himself. His demeanor seemed to communicate: Look, it’s inevitable that you and I are going to know each other — we might as well hurry up and become friends. And we did. Soon afterwards (within the year?) he flew to San Francisco to see the production of my first play. I shudder when I think about the obvious choices I made in that script. But José called me when he got back to New York to thank me and say how watching the play was “all about pleasure” for him — a gesture I was to learn was typical of his generosity.

D-L: As time went on, my interactions with José were seldom but beloved. Always Nao was present, and always there was the apartment, for takeout food and wine, or a disco nap. His capacity to extend himself in late-late-night adventures frightened me a bit at first, not for myself, but for Nao’s equal capacity. I couldn’t help but feel there was a dangerous combination happening there. In the past, Nao surrounded herself with grounding individuals, which is how I like to think of myself (instead of “boring”). But at the same time I was in awe of them both, and curious as to what could happen if two generously social creatures with boundless (read: often fortified) energy were unleashed on the world. What might happen to Nao’s creative production? I had to trust that it would be for the best, though I wrote her now and then to check in, doing my grounding long distance.

Jorge: When I think of this part of José, his endless stamina for socializing, I think of his sofa. That filthy sofa in his apartment that was always hosting an impromptu salon, a gathering. José had this incredible appetite for socializing. Talking. Parrying quips. And, yeah, partying. I couldn’t keep up. Looking back, at its best moments, it was a wonderfully seamless way of engaging with art and with artists. He wrote about my work, he introduced me to other artists, he let me sleep on his sofa, he bought me drinks and he gave me dating advice — it was all part of the same conversation to him; he showed me how it was all connected. The venue didn’t matter. The hour didn’t matter. He didn’t stand on formalities. At its worst, though, the partying gave me many occasions to worry about him.

D-L: We both use this word “generous,” which by memorial standards is cliché. But anyone who knew José probably has that word at the top or near the top of their list. Every time I saw him he engaged me about my work in ways that showed he was putting at least as much thought into what I was doing as I was. Multiply that by the huge number of people José took under his intellectual and caring wing and it starts to feel almost inhuman: all that humanity! He would always talk about the essay he was “going to” write about me. I’m the one who inserted those quote marks. It wasn’t that I thought he was making it up, but that I assumed that while he meant to write something, he’d probably never get round to it. After all, he had such a long list of artists he rallied behind. Then one day he sent me what he called “the rough notes” for that essay, and these notes already had so much thought and careful observation going on in them, I could scarcely believe he considered it only a draft. He said, “Can you give me some feedback and I’ll work on the more comprehensive piece.” I told him I’d see him in New York this winter, and we could talk over a nice meal. I was so overwhelmed by how deeply he considered the work, and how well he captured it in words. What feedback could I give him but, thank you SO MUCH?

Jorge: Barbara Browning said that José was good at seeing beauty. He had a way of showing me back my own work, in ways that opened the work up and made it larger and allowed me to keep going. José wasn’t somebody who shut artists down with a withering put-down, and he wasn’t somebody who used the work of artists as the raw material to try and demonstrate his own cleverness. On the contrary, engaging with José always made me want to create more and made what I did create better. Rare ability in a critic. I thought of him as my ideal audience member, the first person I invited to anything. Having a drink with him afterwards and checking in about the work became part of my artistic process. I just presented the rough draft of something at Dixon Place. This was just two weeks after his death. I considered canceling but knew José would have been against that. I thought of him the whole time I was writing the piece because I knew he was going to like it a lot. But then “was going to like it” turned into “would have liked it.” It was tough to get through the reading. I imagined his responses, his nods or grunts of approval, as I was reading. His absence that night was so felt.

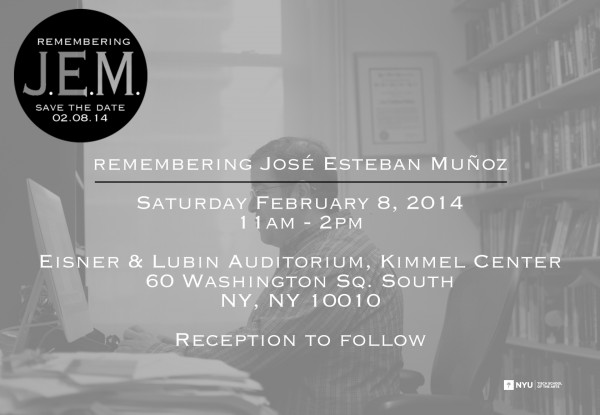

D-L: I’d just arrived in New York (Dec. 4, 2013) when I got the news of José’s passing. It came in the form of a text message. The sender assumed I knew already and wanted to make sure Nao was okay. It took a moment to set in. José and I had a date, how could he not be alive? I turned on Facebook and EVERY entry on my feed was about him. I was taken aback; I had no idea all these people knew José. He must have been everywhere. Former students, friends, colleagues, people who had read his books and based part of their own philosophies on the worlds he opened up for them. Finally I contacted Nao, who was in Troy, packing to come down to Manhattan. There was a small service for José that Saturday, and I would see her there. The service was described as being “just a few friends.” In fact the invite asked people to not invite anyone else, due to limited space. It was at a bar. I expected twelve people huddled there, getting drunk and catching up. Instead, the room was packed with about seventy people, a microphone in the middle. When inspired, anyone could get up and share. The relatively large number of folks at a gathering for just the closer friends was a testament to José’s social skills. An even lovelier testament were the faces gathered: amazing performers, visual artists, writers, and scholars. People traveled across time zones to be there, for what was not even the official funeral. Many of them spoke from the heart quite eloquently on the life and contributions of José, primarily on his impact on them personally. This man built fires under so many talents. He gave permission and encouragement. He created content for approaching a bunch of campy misfits, an intelligent and political content full of generous love. Quite a few of the speakers confessed their daddy issues (Jibz uses that exact phrase) and revealed the pet names José gave them. I stood near the back with my sister, Justin Bond. Family all around us. I saved my tears for the last speaker, José’s brother, who resembles José and even shares some of the same mannerisms. Then many there went to Ricardo’s place for whiskey and fried chicken. Nao and I did too, of course, but first we stopped off at José’s apartment to gather ourselves. The tree under his window — and only that tree in the whole neighborhood — had been tricked by the unusual warm weather into blossoming early. Nao said the night before a band of Cuban musicians stopped at the base of the tree at three in the morning — there directly under José’s balcony — and sang Gauntanamera four times in a row.

“Yo soy un hombre sincero

De donde crece la palma

Y antes de morirme quiero

Echar mis versos del alma”

(I am a truehearted man,

who comes from where the palm trees grow.

Before I lay down my life,

I long to coin the verses of my soul.)

Songs for José by his friend and colleague Barbara Browning

***

Comments (3)

Such a loss — Thank you for posting.

Thank you D-L and Jorge for this beautiful conversation,

which is a ritual

and a gift.

xoxo

very sorry for your and everybody’s loss.

Many thanks D-L and to Jorge for your thoughtful conversation…

and to Nao….

LOVE,