In Search of Christopher Maclaine 10: Stan Brakhage Interviewed, 1986

This is the tenth in a multipart series unofficially conjoined to the publication of Radical Light: Alternative Film & Video in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–2000, and the accompanying film series currently being presented by the Pacific Film Archive and San Francisco Cinematheque (in partnership with SFMOMA).

In my intro to this series, I described my initial encounter with Stan Brakhage in 1986, and the brief interview about Maclaine my collaborators in what would become the Austin Film Society and I were able to do with him then. Subsequent to this interview, Brakhage published Film at Wit’s End, with a chapter on Maclaine, including Brakhage’s personal reminiscences. The interview I was able to conduct with him in ’99 (recently published in Radical Light) added yet more to the picture, and provided the impression of a Brakhage deeply convinced, late in life, of Maclaine’s contribution to cinema — “I think what Maclaine’s done in film is just GIANT …” These later accounts, however, do not supersede the one from ’86, which contains further details regarding Maclaine, and Brakhage’s thoughts on the cultural milieu in which the poet/filmmaker developed, and it is therefore provided for you here now:

“Christopher was considered the Antonin Artaud of North Beach, which was a fiercer place, I’d fancy, than Paris was in Artaud’s time. North Beach was a place of great despair, World War II despair. So many veterans came back and found the nation they had gone to defend had eroded from their idealist viewpoints into the drive for the almighty dollar — (in) the “booming” postwar period … This was a great disillusionment. Many of them pitched into this despair — the driving back and forth across the country, the drinking, or if they had no money, just drinking and sitting in the gutter. Chris was one of the first to read his poetry, often to jazz music, in bars to get his drinks for the evening, or a meal. He had a few books of poetry in print, one of which I’m fortunate to still have a copy of … I don’t know how in the world he decided to make film because the lifestyle he led wouldn’t usually enable him to do so. It wasn’t that he was that much of an oddball — he was just the king of an accepted form of insanity … So Maclaine made these four films (THE END, THE MAN WHO INVENTED GOLD, BEAT, and SCOTCH HOP) in a burst of energy in the early ’50s, culminating in THE END, which had its world premiere at Frank Stauffacher’s Art in Cinema, where it precipitated a riot — not as violent as some of the French riots, but there were certainly chairs thrown, and people storming out or screaming for their money back … For whatever reasons, certainly of which drugs were the primary one, Maclaine ceased functioning as a public poet or filmmaker.

“It was a decade later when I came back to live in Frisco, now with Jane and our first children, when I started looking for the film I remembered from this vibrant earlier period. I was told I could find Chris if I went through this real estate office and paid no attention to the fat old man that would demand to know what I wanted, and just kept on going through the back and out into the courtyard and climb up these steps to the left, and then after six steps stop, stand still and call out for Chris Maclaine, and if he was home I might find him … I heard this voice: “Wadda ya want?!” He told me later the only reason he let me in his window — the only access to his apartment, a strange, walled-off situation where you could only climb out a window to get onto a fire escape to get out — was that I happened to be wearing green pants. He thought anyone walking down the street in Frisco with green pants on must be OK. So he let me in. He often came over to our house, but that became more and more difficult because of the intrinsic violence in him, the knife throwing, the threats to take drugs despite our rule of no drugs in the house. Finally, he insisted on taking something right in front of us and our children, so that was it. I still, however, felt a great need to save his films, and (therefore) set up an appointment with a distributor, which he honored — very rare of him. He showed up with his originals in hand, and signed a contract — also very uncharacteristic of him — thus getting his films into circulation, and more or less preserving them … The next time I came to town I hardly recognized him. They would let him out of the nursing home around noon. He would shuffle around the block in North Beach in his bedroom slippers. He looked twenty years older than he was. His mind was essentially gone — burnt out. He didn’t recognize me at all. Within a year, Chris was dead.

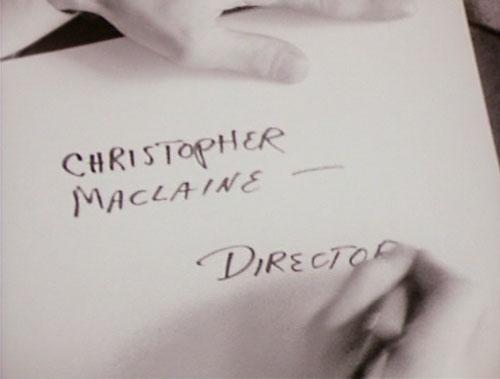

Stan Brakhage in his film THE EXTRAORDINARY CHILD (1954), made the year after he came under the influence of Christopher Maclaine’s THE END

“Though his life may sound tragic by some standards, it is not as tragic as the millions who die in similar circumstances and leave nothing behind. Christopher always knew he was an artist. He knew it well enough that even when he was pitching completely off the cliff, he went to that meeting I’d arranged and signed over his films to be preserved …

“I had heard a story, both from a woman Chris had lived with for a while and from Jordan Belson, who had photographed his (first) films, that he had suffered a severe blow to the head when he was young. He had fallen out of a tree and had brain damage. It certainly didn’t show up in terms of his brilliance of conversation or poetics. This may have effected a very magic retardation, in that he never really passed beyond the teens. All of his works speak in one way or another of a real time loop you could say he remained trapped in.”

—March, 1986

Comments (2)

Yeah, his language is definitely a poet’s, and his voice really gets into you…

i love his narration in ‘the end.’

you can almost hear him stifling a giggle now and then.

http://www.ubu.com/film/maclaine_end.html