“Without the public these works are nothing,” participating with Felix Gonzalez-Torres

For the past seven months, a copy of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s black and white print of a bird soaring through a cloud streaked sky has hung on the wall above my desk. This wall is opposite my bed which means that the print is usually one of the first things I see when I wake up in the morning. I took two copies of Gonzalez-Torres’s print from SFMOMA’s The Art of Participation exhibition last January, carefully rolling them and tucking them in my bag as I biked home. I tacked one above the various photographs, postcards, and notes that have gathered on the wall above my desk and the other I gave to a friend who had just moved into a new house.

During The Art of Participation these prints, known as Untitled 1992/1993, were placed one ontop of another in a stack placed on the floor of one of the galleries. The description of the print lists the printing method, offset lithograph on paper, and then includes this important detail in paranthesis: (endless copies). Visitors were encouraged to take a print home with them and as they did this sculptural stack of paper-thin prints would decrease in size and then would be replenished after hours, probably by a museum staff member, a ritual that will happen endlessly whenever this piece is on view.

The story of Gonzalez-Torres is well known. He immigrated to New York City from Cuba, gaining recognition as an artist in the late 1980s through his minimalist sculptures and installations that often referenced issues of public and private, accumulation and loss. The foundation on which the majority of his work was grounded was his relationship with his long-time partner, Ross Laycock. In 1989 he started exhibiting these stack pieces at MOMA, the Guggenheim and Andrea Rosen Gallery. It was during this time that Ross was dying of AIDS, and the stack pieces represented this process of letting go—they disappeared, yet unlike the inevitability of Ross’s death, the prints would return in their endless cycle of presence and absence. The prints themselves often depicted ephemeral moments; a bird flying or the texture of the surface of the water. These transient moments were captured on film and then in a sincere gesture, extended to others as a gift. Four years after Ross’s death, in an interview with Robert Storr for ArtPress, Gonzalez-Torres said, “When people say, ‘Who is your public?’ I honestly say, without skipping a beat, ‘Ross.’ The public was Ross. The rest of the people just come to the work.”

While Gonzalez-Torres’s stacks function as homages to his most cherished relationship, they operate on another level altogether. The endless prints designed to be taken from the museum dislodge the institution from its role as a sanctified space in which visitors view art and don’t interact with it. They challenge the authorship assumed by individual artists within this space. Sure, the prints exist within the galleries, the stacks functioning as sculptures as much as they are a practical means of disseminating the prints, yet, the participants in Gonzalez-Torres’s piece are given the power to recontextualize the work through their own personal environments and interpretations. After The Art of Participation exhibition I started to notice these prints covering the walls of many of my friend’s homes. Their homes became informal exhibition spaces; the residents who inhabit the homes and guests who visit become impromptu viewers taking in the work or acknowledging it as background decor. While the work was made for Ross, the greater public is an integral component. Gonzalez-Torres said, “Without the public these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in.” And it is true, without our participation, the stack pieces wouldn’t function according to their intentions. Yet, this is about more than just participating in the function of a work, it is about sharing in Gonzalez-Torres’s grief and the lesson of letting go. Gonzalez-Torres makes the work for Ross and then disseminates it to the broader public as an endless gift given without restricting its interpretation or use.

Once it leaves the museum the contextualization and interpretation of the print is open—horizontal versus vertical, the bird ascending or plunging downwards. I am always a little bit surprised to find the Untitled 1992/1993 print hanging in a direction different than what I interpreted as its most natural orientation (horizontal with the bird ascending). In the photograph of the print sent to me by Paola Santoscoy there is an interesting relationship between the image and the environment of her bedroom. Her bed makes its way into the bottom left frame of the photograph. Its messiness and the white sheets and pillow is reminiscent of the bed featured in Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled billboard piece from 1992. Gonzalez-Torres’s billboard features a photograph of an unmade bed with two white pillows that preserve the imprints of two bodies—deep indentations in the white fabric where two heads rested. This photograph was made the year after Ross’s death. It speaks to the loss endured by Gonzalez-Torres and the attempt to preserve the ephemerality of their relationship in the face of Ross’s illness. Displayed on 24 different billboards, Gonzalez Torres’s loss became part of the New York City landscape, yet another public acknowledgment of his personal grief. While Santoscoy’s photograph lacks the intentionality of Gonzalez-Torres’s billboard, as an informal snapshot of the print taken by my request, I find something comforting about the Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled 1992/1993 print returning to the private context of a bedroom and photographed in such a way that the lineage of his work is suggested through the visiblity of the bed, the site of intimacy for Gonzalez-Torres and also a symbol of loss.

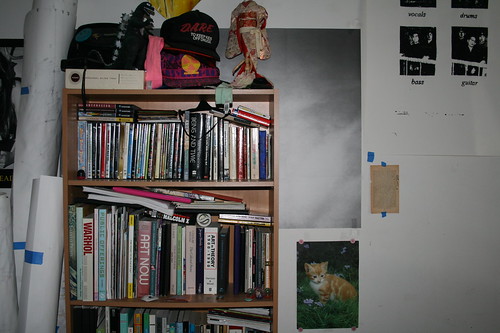

In James Bradley’s bedroom Untitled 1992/1993 fades to the background, one third of the print peeks out behind a crowded bookcase. Here, the work is one of many room decorations, receiving even less attention than a highly saturated color image of an orange tabby cat posing among flowers and grass. The print from MOMA functions as wallpaper, some layer of a past decor that has since been deemed undesirable or forgotten. There is something incredibly un-precious about the give-away aspect of this work. Gonzalez-Torres relinquishes control over the display of the prints beyond the museum. For as many prints as there are that were carefully carried home from the museum and hung in just the right location, there are prints that never made it, that were bent, or later discarded, have faded to the background, or are glanced at once or twice and appear unremarkable without the story of Gonzalez-Torres that is imbedded within them. In a sense, the importance of this work has more to do with the act of taking them away than it does the recontextualization that occurs through the various locations that the prints end up in.

I love imagining the invisible web of homes across the Bay Area that now hold this Gonzalez-Torres print. These homes contribute to a potentially endless network of informal exhibition spaces that grow over the years as Untitled, 1992/1993 and other prints continue to be shown in national and international exhibitions. The participants have the opportunity to form their own relationship with the piece, as the photographs here have shown. While the endless prints quickly outlived Gonzalez-Torres, his own death from AIDS complications was in 1996, seventeen years after they were first displayed, they continue to be a gift given from him, for Ross, and for the public that Gonzalez-Torres relied on.

Thanks to Paola, James, Eric, and Nicole for the photos.

Comments (4)

Currently looking up at mine while I read this article in my place in Madison. Though I picked it up from the stack years ago for some reason I just now looked up the artist. I love knowing the story behind it. Love knowing the artist is also gay and that this art came from love and grief. It’s always comforted me immensely but I feel even more connected to it now. It’s wrinkled and will just get more and more as I take it to each new place I live.

I’m looking at mine right now, in the Hudson valley area of NY. It’s traveled far and wide with me, moving on average every 6 months since 2009 has left the print bent, warped, and wrinkled and edges taped to continue to be able to tack it to the wall or ceiling of wherever I go. I think I don’t really feel at home until it’s somewhere over my bed.

Such a great and beautiful idea and that double meaning to this “distribution”, something I would have liked to share..

(I love what you have on your Mac’s screen by the way, a desktop image? I want the same! please 🙂

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l7_Zu2AQyQ&feature=related VIVA FELIX! VIVA!