A Queer Time and Place

June is National GLBTQ PRIDE month and my next couple of posts will respond to art events sponsored by the National Queer Arts Festival. Despite being late in the month, I hope these posts generate some discussion about the notion of queer arts and PRIDE month, more generally.

Last week I joined a sold-out, yet intimate gathering of people at The Garage for the film screening, Across Queer Time. Curated by artist, Jason Hanasik, Across Queer Time was part of the 12th Annual National Queer Arts Festival and featured thirteen artists including Rudy Lemcke, Curt McDowell, Marc Adelman, Tammy Rae Carland, Jesse Finely Reed, Barbara Hammer, Kristina Willemse, Tina Takemoto, Jennifer Parker, Cheryl Dunye, Julian Vargas, Margaret Tedesco, and Killer Banshee. Hanasik introduced the films describing them as oscillating around tension—fantasy, the world in which we wish we existed, and nightmare (which is, perhaps, part of our reality, as well). Indeed, the films cascaded through themes of illness, the fear and reality of AIDS, the intersections of racial identity, religion, and sexual desire, private spaces of homes and intimate relationships, and public interventions and demonstrations. Throughout the evening and over the past few days the title of the film screening continues to echo in my mind—across queer time. This title is especially thought provoking within the designation of June as National GLBTQ PRIDE month, a sanctified 30 day time period in which people throughout the country celebrate and pay homage to GLBTQ history—many of whom flock to San Francisco to participate in the overwhelming number of events, parties, parades and marches.

What exactly constitutes queer time? How is time, and consequently space, understood through queer identities? How do the films featured in Across Queer Time represent this experience? In my own thinking, experience, and more formal research (influenced mostly by Judith Halberstam’s recent publication, the title of which I borrow for this blog post) queer time can be defined as a way of being that exists beyond the linear and conventional notions of familial institutions and biological reproduction. It allows for a reinterpretation of family and a radical reformulation of kinship. Queer time also emerges in the context of struggles that are inherently political and personal, such as the AIDS epidemic and the communities formed through collective action and protest. Yet, the films chosen by Hanasik refuse to be directly defined by any formalized theories of queer time and I think their success lies within this refusal. Hanasik made a point to include an intergenerational perspective in Across Queer Time with films ranging from 1974 to 2009. More than this obvious relationship to time, the films featured non-linear narratives and film sequences, and made visible queer spaces, the slippages in identities, relationships, while questioning the time and space in which these experiences exist. The very designation of the term “queer” attempts to dislodge itself from a gay/straight dichotomy to exist within a liminal space of non-definition.

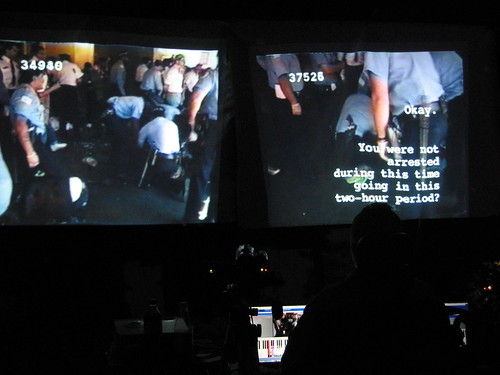

The notion of queer time as it relates to political struggles was present in the live video “Unleashed Power” performed by Killer Banshee during Across Queer Time. “Unleashed Power” consisted of footage from an Act-Up protest in Chicago from 1991. The two channel video followed the story of one incident of police brutality and arrest, jumping from still images of the protest and a mug-shot, to looped footage of the violent attack. The images were combined with written and spoken transcripts of the deposition given by one of the survivors. The repetition of the footage and attempt to connect the image, sound, and written word spoke to the reconstruction of memory, both for one individual and those present at the protest, as well as the recollection of a specific moment in the history of the AIDS epidemic and the history of civil disobedience that has all but ended for the individuals featured in the film footage and for us as a society. More than any other point throughout the evening, the intensity of “Unleashed Power” made me extremely aware of my body as well as the trajectory of time from the prominence of political organizations like Act-Up to our current political moment and back again.

Perhaps more than the films themselves, the consecutive ordering of certain films challenged the notion of queer time and left the audience to do some of their own work in defining what exactly that means. For example, Barbara Hammer’s 1974 film “Dyketactics” featured a small group of women together, nude and in the woods, and culminated in aerial and close-up scenes of two women having sex. Hammer’s film was followed by Willemse’s “Little Sheep,” a film that begins with two young girls whispering, playing and grooming one another. These seemingly benign scenes are interrupted by images of a hand moving dolls throughout a dollhouse, close up shots of texture, color fields, and what appears as blood moving slowly through water. Without giving us too much information, the shifts in imagery of “Little Sheep” communicate a sense that some violence has occurred, interrupting the innocent and sweet rapport between the adolescent girls—perhaps something lost in moving from adolescence to adulthood. In moving from an intimate scene of lesbian sex from the 70’s to a recent film featuring adolescent girls the site of queer identity formation is questioned. For Hanasik, “Little Sheep” challenges the assumption that we don’t join a queer community until later in life. Indeed, the common narrative of “coming out” implies an action that occurs in one specific time and place, an experience which I think many people would agree does not take into account the fluidity of identity, nor the constant negotiation of one’s identity within different contexts. In other words, the time (and space) of “coming out” is not static, but rather continues to evolve.

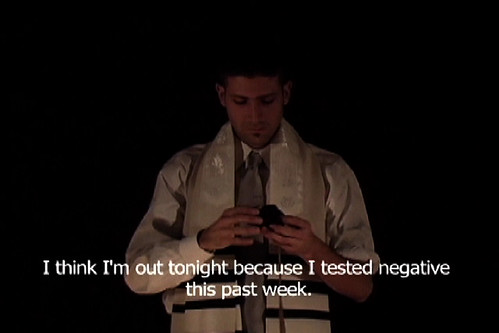

Another example of this movement occurs between McDowell’s documentary-esque film “Ronnie” from the 1970s and Adelman’s recent “Samstag Abend im Eagle (Saturday Night at the Eagle).” “Ronnie” features a monologue of a man who attempts to keep his identity as straight stable while describing his experience having sex with another man for pay. The narrative is surprisingly casual and almost flippant. Following this confession, is “Samstag Abend im Eagle (Saturday Night at the Eagle)” a film in which we observe a more contemporary, albiet no less complicated negotiation of sex and identity through religion and illness. “Samstag Abend im Eagle (Saturday Night at the Eagle)” invites viewers to witness the artist as he participates in tefillin, the Jewish ritual of wrapping one’s arms and head in leather scrolls before reciting morning prayers. However, rather than wrapping his head, Adelman wraps his penis in the leather scroll while a monologue in German describes his encounter with another man at the San Francisco gay bar, The Eagle Tavern. The narrative describes the negotiation and conflict that arises in learning that this man is HIV positive. In moving from the very matter-of-fact description of sex between two men in “Ronnie” to Adelman’s film which takes on a serious and confessional tone, the viewers are reminded of the weight of the AIDS epidemic, which was not a concern during the time that “Ronnie” was filmed. “Samstag Abend im Eagle (Saturday Night at the Eagle)” also challenges the specific time and space of such an experience; we listen to a man’s story that takes place in a gay bar while witnessing his enactment of a sacred religious ritual. Through these careful pairings, time expands and contracts. Where we may have settled in one film, we are uprooted in the next.

As San Francisco prepares itself for the approaching PRIDE weekend, the question of queer time and space is highly visible and palpable. Yet, the rainbow flags donning the lightposts along Market Street and throughout the city represent a very specific queer time and space—one sanctified and let us not forget, sponsored. While the historical lineage of this celebration is important to recognize, I hope it comes with some criticality, as well. And the acknowledgement that beyond the designation of the month of June as GLBTQ PRIDE month, queer time exists—in moments that are transitory, both private and public, political and personal, and that, much like the experience of traveling through the films, represent an experience of time that does not settle.

Comments (3)

Dear Adrienne,

Thank you for this fascinating post. Although I didn’t get a chance to see “Across Queer Time,” I am really interested in the provocative questions you raise here, especially around the possibility of viewing time and space as “queered.” Much of what I feel you are engaging with is the idea of telos or genealogy and this feels especially prescient during Gay Pride month in San Francisco. You mention the juxtaposition of both “Dyketactics” and “Little Sheep” and “Ronnie” and “Samstag Abend im Eagle (Saturday Night at the Eagle)” as revealing something about the legacy of the AIDS epidemic and our current moment of living queer in an (erroneous) “post-AIDS” queer landscape. Gay Pride month to me has always seemed a moment to critically reflect both on our current activism and historical legacies. How can we see queer time critically in these contexts? Have we moved from a place of death and disease to a place of safety, and if not, why do we feel this false sense of security?

I was also really interested in your discussion of “coming out” as no longer static or fixed but possibly mutable or fluid. In the 1970 the rallying cry during Gay Pride was always about coming out as an issue of safety, to make the queer community visible as a political force (and consumer class). Have we moved away from this? I agree that in our immediate social networks, it seems less and less important how individuals identify and our relationships are often organized with greater flexibility than in past queer configurations. But is coming out no longer necessary politically? How, then, can we reenvision our queer political allegiances and who holds the right to claim a queer politic? Could this be a call for a stronger and more complicated queer political community, one which sheds some investment in personal identity over collective unity?

I also see the utility of Gay Pride as an opportunity to actively critique the larger gay mainstream agenda which privileges capitalist doctrines of hetero-assimilation through marriage and the patriarchal family etc. etc. We have heard this one before, no? But what your essay brings up for me are more complicated questions of living simultaneously in the past and present, engendering investment in a queer critique that starts from a historical perspective like the arrest at an ACT-UP protest or even one we feel less compelled by (like 1970s lesbian wood sex). What would our activism look like emerging from this historical perspective, utilizing a kaleidoscopic gaze of queer moments?

I am not sure if that makes any sense at all.

Thank you for your work.

As I mentioned Hanasik made an intentional decision to incorporate films from since the 1970s to today by artists who represent a range of ages and experiences. In addition to “Dyketactics” by Hammer and “Ronnie” by McDowell, both made in the 1970s, was Cheryl Dunye’s 1994 film “Greetings From Africa” that follows Dunye negotiating the world of lesbian dating. None of the films in “Across Queer Time” struck me as confrontational in the sense that you described, even Killer Banshee’s video performance “Unleashed Power” that had the potential to be read in a purely activist tone retained a nuanced and personal sense. What I think is interesting is that the term “queer” is relatively recent in respect to today’s generation moving away from the distinctions of gay or lesbian to language that incorporates genderqueer people, transpeople, and a fluidity of gender and desire. Maybe not so pointedly, but I think the most recent and I believe the youngest filmmakers featured in “Across Queer Time” represent this nuance – Willemse’s “Little Sheep” and Vargas’s “Ka. Ka” a film in which the artist splits his body to play two brothers Augusto and Rosetta Guerrero. These films were all but aggressive – subtle, beautifully made, with thought provoking narratives.

I was reminded again this weekend of San Francisco’s role as an safe place for GLBTQ communities as thousands of people from out of town poured into the city for the PRIDE festivities. The gathering at Dolores Park on Saturday for the Dyke March was, indeed, multigenerational. I agree that the Bay Area is in its own league, however struggle still exists and however, I think because of this there is an incredible amount of activism and art practice that expands what we think of as queer or queer related. There are many more thoughts on this – I will leave it here for now and hope to continue the conversation in future posts and/or comments.

Adrienne, can you talk more about the intergenerational perspective you mentioned? I often feel that contemporary “queer” film and art remains lodged in a vernacular of the 1970s and 1980s activist generation, in which queer identity is a site of extreme tension and confrontation, necessarily presented with an aggressive posture. That seems worlds apart from the Bay Area queer experience of the present day. Yet for most of the world, queer life remains fraught with danger, ostracization, persecution. How were (or weren’t) these divergent perspectives and all the nebulousness between them presented?