Three Julys

I was content to set out in a different direction each day. Teddy was a strong eight-month-old that first year I took care of him, and he tended to drag me at a pace that rarely let up. By the second year he was accustomed to the leash, and we found a more balanced and compatible way of meandering around the city.

My three consecutive Julys in San Francisco began with a lunch in New York City, at a West Village restaurant called Moustache. It was March of 2017. My friend was in town to work at one of the annual art fairs, and we were pleased to reconnect over a good meal. I talked about the possibility of relocating for full-time employment as a teacher; he suggested I take care of his house and dog while he and his family were on vacation. It was a generous offer — unexpected, exciting, and viable at once. I think his invitation was in part motivated by him sensing that I could use a break from New York. Those summers proved to be life changing.

That first year everything was new to me. Even when facing the inevitably tiring hilly terrain with an inexhaustible and slightly aggressive puppy pulling me along, I was open-eyed and observant. I was spending hundreds of hours alone, and Teddy and I went for very long walks. The sidewalks and parks were generally quite empty; Teddy sniffed the air for illusive coyotes. Being on foot allowed me to notice levels of grit, character, glamour, hardship, and history as I passed through each neighborhood, a temporary inhabitant of the city. Everything I observed was from an arm’s distance. I rarely rode the train or buses. I used the dining room table as a place to draw.

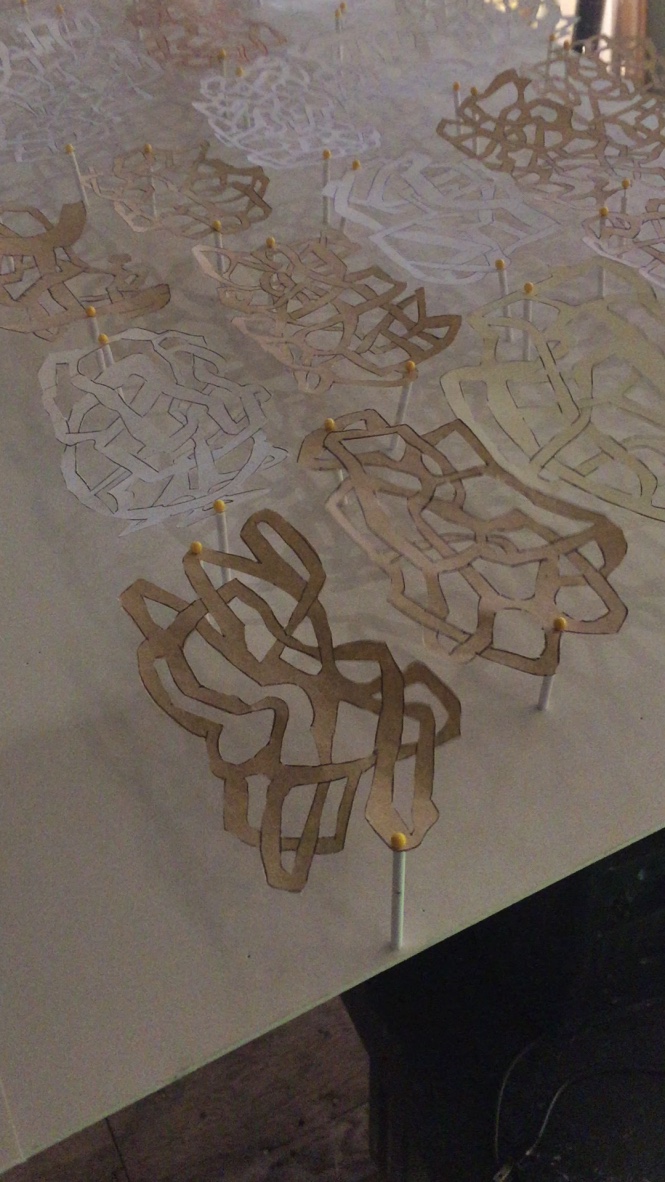

The physical act of continually forming and shaping language on a piece of paper makes me notice how words are composed of visual and choreographic variants such as hard or soft lines, careful or rushed lines, and lines that turn into doodles or scribbles used to negate a word. Although the drawings sometimes look like filigree (or complex patterned pathways associated with a semi-regimented dog walking routine), that was not my intention. Rather, as an evolving exercise, the ability to re-draw visual forms that are roughly similar allowed me to work in inexhaustible sequences with no arrival point, without finality. In some ways, the drawings reflect the transitional nature of being an aging dancer whose body is an instrument in flux.

The summer of 1991, two friends and I drove across the country. San Francisco was our final West Coast stop, and we could only stay for a couple of days; we had to get back to New York City where we all lived. When I think back to that first visit, I remember the scale of the iconic theater marquee in The Castro, and the quality of bright sunlight on the washed-out, pastel-colored clapboard houses lining the streets. I noted that the architecture was predominately three-to-six stories tall and that it was made of somewhat unstable materials such as wood, as opposed to concrete (an architect told me that the pliability and relative impermanence of wood as a construction material was favorable in boomtown cities like SF). I was unaccustomed to seeing an urban center replete with fantastic plants. Flowers and potted gardens appeared to spill out of peoples’ homes. The commingling relationships between the scenic views, light pedestrian traffic, large bodies of water, and swift blankets of fog were atmospheric and inviting. I imagined what it would’ve felt like to see Harvey Milk on the sidewalk. I pictured his confident composure, his handsome and charismatic smile, his casual yet forthright and intelligent manner.

Dancers in Moscow made me a t-shirt as a parting gift. The writing on the shirt appeared to be a riff on my frequent verbal prompts: all we need … just a little adjustment. Through an interpreter, I urged them to examine small gradations of movement. At times, they appeared overly concerned with comportment. The gift seemed like an affectionate and symbolic sendup of John Lennon’s song, “Give Peace a Chance” (“all we are saying … is give peace a chance”); is it a reach to think that my students made a deliberate connection between the sentiment of Lennon’s lyric and my instructions? I’ll never know. Teaching at the festival gave me a tiny cultural window on Russia. Similarly, I gleaned new information about the dance ecosystem in San Francisco. Jennifer Perfilio invited me to create a dance for Shareen DeRyan and Leyna Swoboda. The duet was performed in a studio at ODC for a small group of invited guests. I also participated in group improvisations at CounterPulse and the Center for New Music.

As a gay teen in New York in the charged 1980s, San Francisco loomed large in my imagination. The reality of finally being on its city streets, given these years of anticipation, was enlivening — to put it mildly. Safety in numbers, the quest for emancipation, being alive, and noting which cities had a concentration of gay people: all of these held a different, weightier meaning than they do now in 2021. As an alienated fifteen-year-old, I used to take the subway from Brooklyn into the city, seeking to connect. Being in lower Manhattan was the only way to take in a life I sought, one to which I had no access. In some respects you can be gay anywhere now. You can even campaign to be the president of the United States.

By my third July taking care of Teddy, in 2019, I had greatly expanded my understanding of what living in the San Francisco Bay Area for a month could mean. I rarely tired of being tethered to my state of pit bull ownership, which grounded me in a way that I hadn’t expected. The metro allowed me to feel less isolated. I went to Z & Y Restaurant for dan dan noodles, and the David Ireland House for respite from pounding the pavement. As I passed countless facades, I became more aware of my limited curbside view of city life; I wanted to connect with people in their homes. My visit to the elegant and moody Ireland House transported me to a very particular and personal kind of interior home life. It excited me to see the way Ireland used extant materials such as wood flooring, window casements, and plumbing to transform his dwelling into an enterprising sculptural entity. I was also spending time at Telematic Gallery, where I had been given a performance residency. I occupied a long rectangular white room with a concrete floor, wall-mounted monitor, and ceiling-mounted projector; in one corner, a glass door provided indirect sunlight and opened onto a concrete backyard. The backyard was spacious, and a little neglected. I very much enjoyed the creaking of the tall leafy trees gently bending in the breeze. I wondered what the former tenants of the building (a leather shop) would do in the backyard. They left behind inspired-looking graphic signage. The signs were handmade and had the quality of an artifact, something to be saved.

I collected copies of The San Francisco Chronicle and used them to pad, warm, and soften the hard floor so that I could dance without bulky clothing or shoes in the sometimes-cold gallery. The act of partitioning the space with newsprint shaped my movement choices. I edited rehearsal footage that I had shot over the past many years, a process that allowed me to reconfigure passages of choreography and improvisation. Spliced scenes of dancers at work in a variety of locations (not on a stage) disclosed intimate corners of human experience, a cogent testament to life in the performing arts.

Performers featured on video: Omagbitse Omagbemi, EmmaGrace Skove-Epes, Simon Courchel, Nico Brown, Jodi Melnick, Jeremy Pheiffer, Jennifer Miller, Stuart Singer, and Jon Kinzel. Video and photographic documentation at Telematic by Christine Regan, and Jon Kinzel. Performance residency supported by Clark Buckner, Director of Telematic Media Arts.

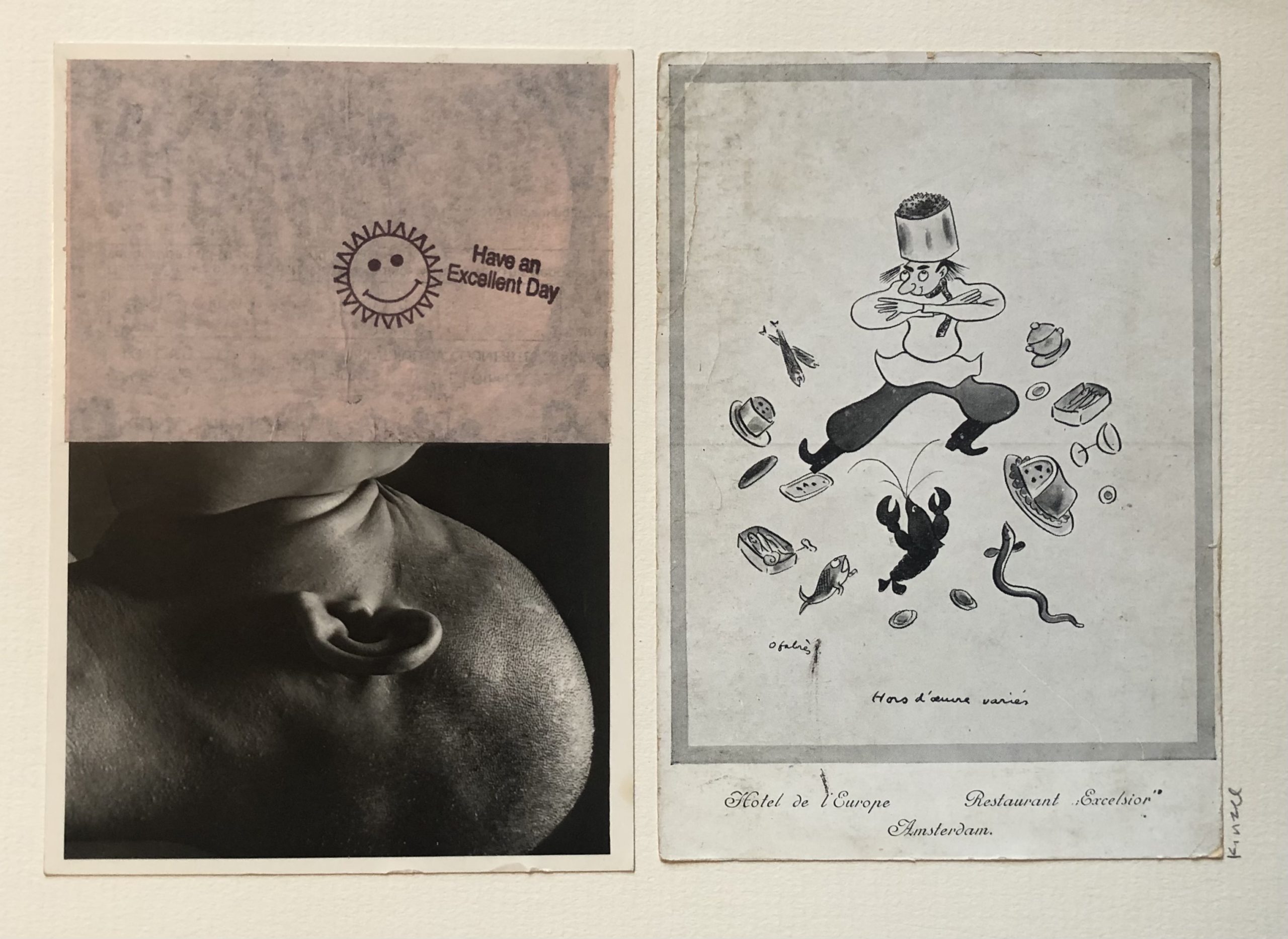

The video provided me with a way to bring other dancers and parts of New York into the gallery. Additionally, it created a frame of reference for people who came to my open studio days. I used the signage from the backyard, coupled with depictions of the body on video, to help bolster and define my weekly public performances — the artifice of fiction meets an experimental memoir of sorts. In the spirit of being on-the-road I wanted to find useable information/sufficient source material while on the ground, through observing my surroundings. I didn’t mail supplies from New York; I brought what I could carry. I conveyed the notion of “specificity inside informality,” as my friend, the choreographer Vicky Shick, has said. I didn’t have ambitions to greatly transform the space.

The performance residency gave me an opportunity to look back and look closely at an ongoing practice that I had initiated in a 2016 project called Atlantic Terminus, an installation at The Invisible Dog Art Center in Brooklyn. I used the title Pacific Terminus to frame my experiments and research while at Telematic. Working remotely in collaboration with conceptual artist Bob Ajar, I produced a loose collection of drawings and paintings, video, sculpture, and dance forms which variously address technology’s effects on visual culture, social relationships, performance, and the presentation of the moving body. During open studio days, the public was invited to share the space with me while I explored relationships between improvisation and composition, and unforeseen ways of connecting dance, sound, and object-making within the temporal realm and the wider world. An important aspect of the residency involved organizing and recording three in-person interviews. I spoke with a writer, a poet, and a visual artist. A portion of each interview contained dialogue that took into consideration the time before and the time after the advent of the personal computer, the internet, and the smart phone.

Howard Junker and I discussed his book, Lord Jeff & The Closet. Both investigative and personal, his research reveals a detailed and historically significant account of repressive codes and homophobic culture. Junker attended the University of San Francisco and founded the literary journal ZYZZYVA. This audio file contains excerpts from our talk at Telematic in July, 2019.

The meditative, cozy artistic practice I was inhabiting was radically juxtaposed with the anything-but-cozy Dore Alley street fair happening just outside the gallery door. I wove through the teeming streets: thousands of partially dressed people in leather were celebrating in the blazing sun. Loud music, the smell of grilled sausages, and a handful of vendors was the only thing Dore Alley had in common with other street fairs. It was oddly comforting to gather in a public location with so many self-possessed sexual souls. A guy posing nude for pictures in an unapologetic stance — more ‘take it or leave it’ than mysterious or erotic — symbolized a palpable form of solidarity and acceptance that, to me, felt particular to San Francisco’s urban culture. People performed non-romanticized, time honored, and artful bondage practices followed by consensual flogging sessions. These were presented as educational demonstrations. It was as if I were watching a startlingly compelling yet benign cooking show designed to impart rare and helpful secrets of the trade.

Photography credits: Paula Court, Alex John Beck, Madeline Best, Julieta Cervantes, Scott Shaw, Erica Freudenstein, Richard Termine, Christine Regan, Antony Shipman