Flânerie and the Making of Place: Janet Delaney in Conversation with Robin Abad Ocubillo

Janet Delaney started photographing South of Market in 1978; she has been chronicling the transformation of the urban landscape and its inhabitants over several decades. I arrived in San Francisco exactly twenty years later, so there is a neat kind of symmetry with this interview happening in 2020. In the last two decades I’ve accumulated my own perspectives on how and why our beloved city has changed.

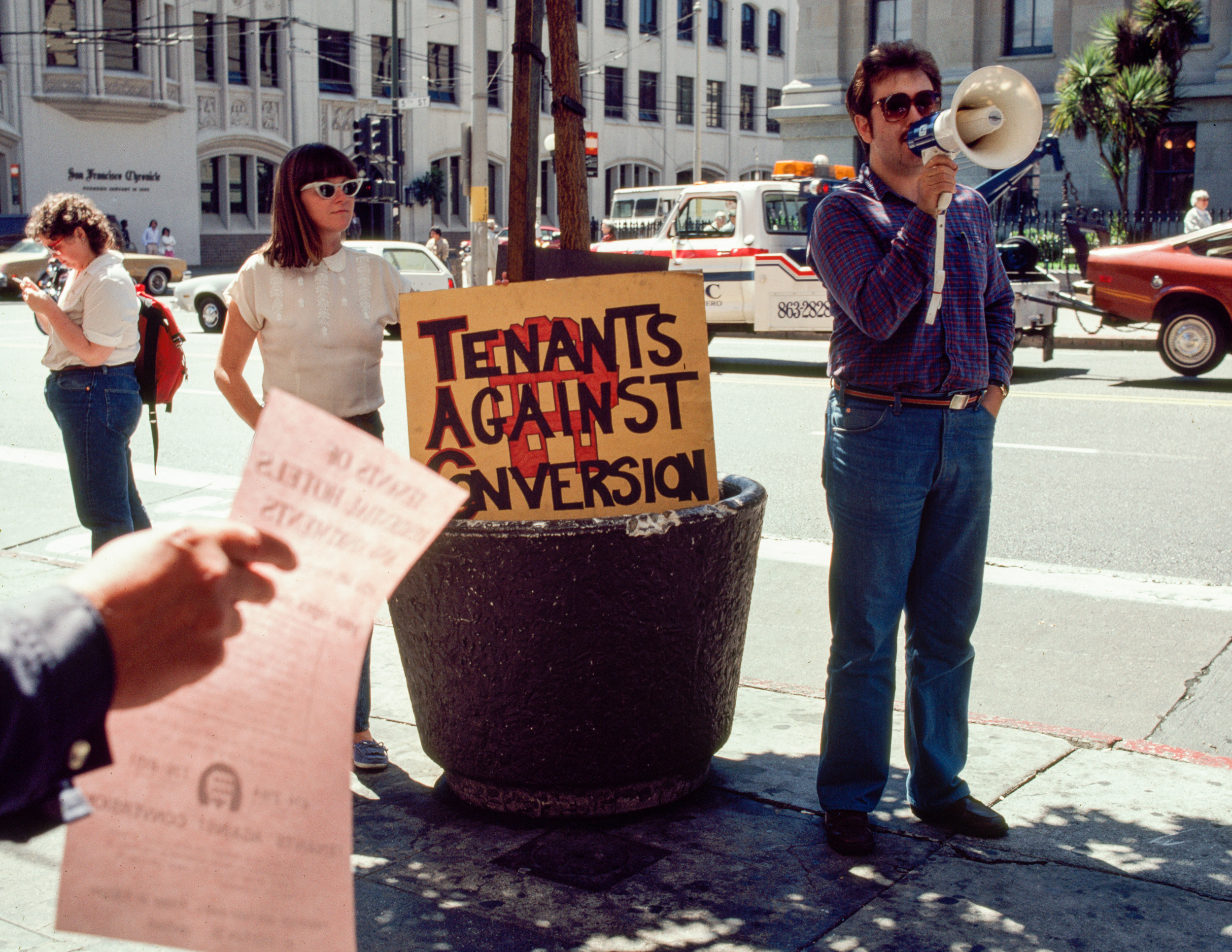

In this conversation I wanted to explore the sympathies between the photographer and urban planner, the relationship between an artist and her subject (in this case, place), and how social upheaval is reflected in the evolving values of arts institutions. Most importantly, Janet and I reflected on how she as a photographer participates in urbanism — as documentarian, community organizer (as with her neighborhood installations in the 1980s on Langton Street and in 2016 on 6th Street), and place-advocate. Throughout the conversation, Janet and I are also in dialogue with works from her series South of Market (1978-1986) and SoMa Now (2010-ongoing).

This is the first of three conversations for this issue of Open Space magazine exploring participatory urbanism through the lenses of artists, community organizers, and advocates. –RAO

All photographs by Janet Delaney; images are courtesy of the artist and Euqinom Gallery.

-

Bobbie Washington and her daughter Ayana, 28 Langton Street, 1982 -

Jill Scott and Perry Lancaster in their studio at 71 Langton Street, 1981

Robin Abad Ocubillo: In 1978 you moved to Langton Street, in South of Market. This wasn’t very far from a huge construction site that was being redeveloped through urban renewal; the site fascinated you for a number of reasons.

Janet Delaney: Yes, I was thrilled to find a site so close to home; I had been driving out to Petaluma and beyond to photograph construction sites. In my initial approach to photographing these places I was searching for abstract content; I was concerned with formal issues — until one day I had an epiphany as I was down in the pit on Folsom and 4th Street, trying to organize the rebar and the nakedness of a construction site into something meaningful. There was a moment when I looked up over the edge and realized that there had been thousands of people who had lived and worked at this exact location before it was bulldozed; this idea washed over me in a way that epiphanies do, opening up my mind to a more public and integrated concept for my own artwork. I sensed that if I looked around the edge of the construction site, at the blocks of homes and businesses that still existed, I might be able to make photographs about what and who had been displaced by the forces of urban renewal and the concurrent market forces of increased housing costs.

I poured over as many old photographs as I could find, to try to visualize what had been erased. The work of Ira Nowinski in No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly was really pivotal in terms of my understanding about the SROs, the single resident occupancy hotels that had been demolished and the people who had been moved out in that process. I attended planning meetings held by the city to get community input. I read Yerba Buena: Land Grab and Community Resistance by Chester Hartman. His book carefully outlined the narrative of political struggles that happened as a result of redevelopment and their long-term effects. This book really influenced the way I approached photographing my neighborhood.

RAO: Who were you photographing and were you making intentional choices about who to seek out, certain situations or certain types of communities?

JD: I was photographing my immediate neighbors on Langton Street: artists, Filipino families, Black families, my gay landlord. I would wander the main streets and side alleys looking for businesses where I could walk in and introduce myself. I photographed in auto shops, print shops, a bakery, a casket factory, cafes, barbershops, any place where I could call out from the doorway and say hello. I made the decision to use a large format camera, which really shaped how the work was produced and experienced. In this way I took up more space, which was my intention. There was a kind of camaraderie that came from me working with my big camera while the people I was photographing were also working behind the counter or wielding their arc welder.

Making a social documentary project with a view camera and color film was an unusual choice in 1980; people still associated documentary work with grainy black-and-white images made with a 35mm camera. My choice to use this large-format camera and color was motivated by my need to give a sense of importance to this place. I wanted to honor the residents, workers, and business owners with my art. I wanted to draw attention to a neighborhood that had been so maligned that the center of it could be demolished to build a convention center.

South of Market wasn’t an obvious iconic neighborhood, like Chinatown or the Mission. It was a place that came to life on the weekdays as a commercial center and sort of disappeared on the weekends, with the exception of the gay bars that light up late into the night. It had been developed as a light industrial warehouse zone with housing for the workers woven into the space between the factories. On Saturday and Sunday the streets were very quiet. There were no parks or other amenities, no grocery stores, there was just one school that was struggling to stay alive.

-

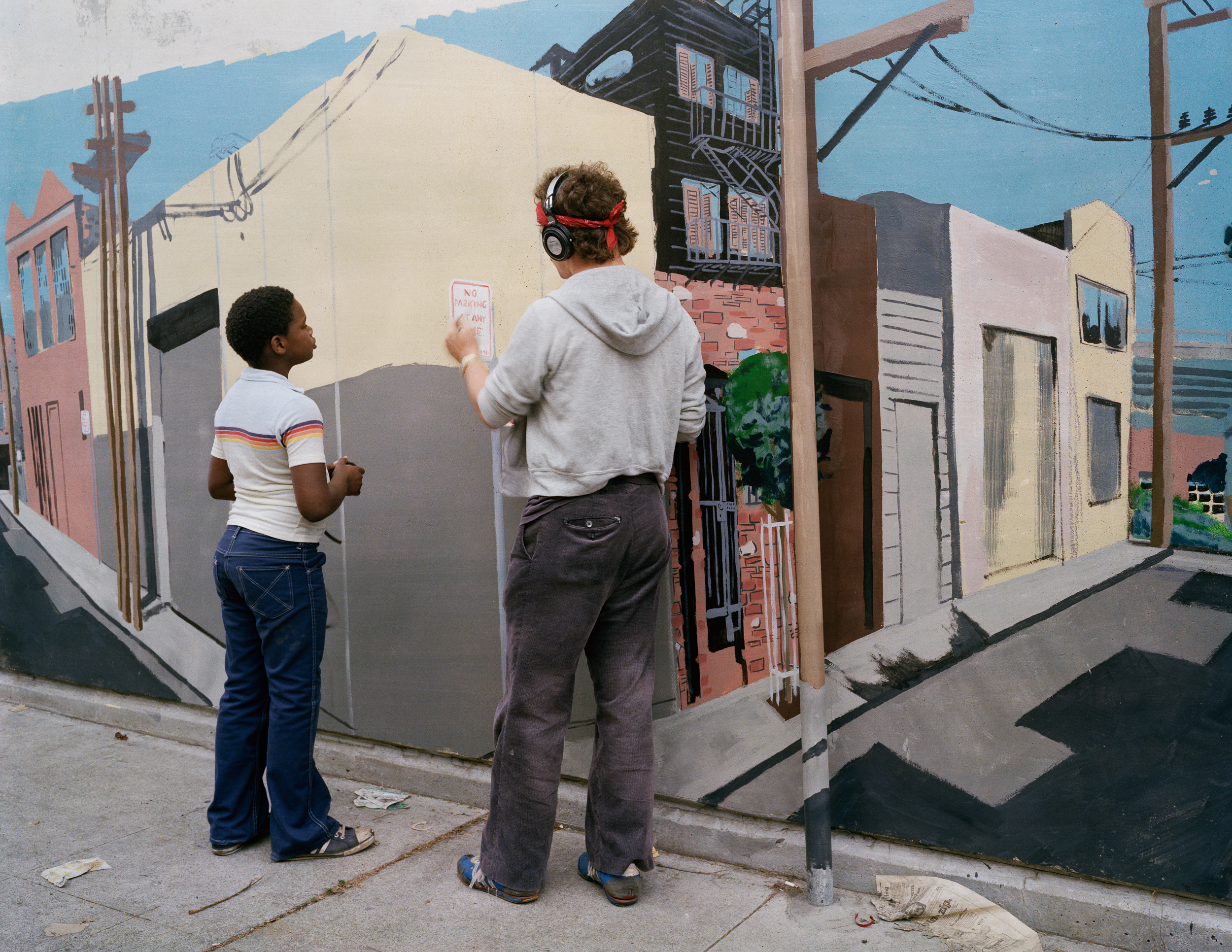

Community Activists, 5th at Mission Street, 1979 -

Demonstrators, Democratic State Convention, Moscone Center, 2019

RAO: You were photographing residents in their apartments and artists in these converted warehouses. You knew there was a displacement effect or an eminent displacement washing over the neighborhood, the city. There was also a newly arrived gay community in South of Market that was gaining prominence and political power.

JD: Even back then there was a lot of pressure throughout San Francisco on housing because of the rising cost of rent. People were moving back into the city in the 1980s, disappointed by the blandness of the suburbs. You may recall there was that term, Yuppies: Young Urban Professionals. Women were joining the professional workforce in increasing numbers. I never felt like a Yuppie because I certainly did not have a professional job, I was working as a union bartender and then as a printer in a color lab — but I was white, and I was an artist and I was paying twice what the people before me were paying in rent.

South of Market was the least expensive part of town so there was a lot of interest in it from those who wanted to live a less traditional life. In my conversations with long-term residents, I could hear how anxious everyone was about the changing demographics. My neighbors were noticing the artists who were converting empty warehouses into studios and the gay men who were buying small apartment houses and transforming working class bars into gay night clubs.

The tow truck in the background is so perfect. [Laughter] It’s just like, things aren’t going well. We got problems. Nothing like a tow truck to symbolize a bad day, right? This is in front of that hotel, Pickwick’s, I think. It’s been there forever and I guess they were in the process of trying to convert it to condominiums. It was a challenge to picture gentrification in the 1980s, it was not yet very visible.

RAO: So, Langton Street, 1978. What was it like?

JD: There were warehouses at the end of the street and it was a marvelous little street. One of the things that happens when you have a narrow street is that you have a lot more interaction with people. As the streets get wider, there’s more physical distance, which creates social distance. So because of the kind of closeness, we were able to chat up our neighbors. But the street was pretty bare, very utilitarian, and full of trucks during the weekdays. There was a constant backup of traffic; the UPS truck was always making deliveries. Because my studio/darkroom was in my apartment I didn’t feel alone during the day; I knew I was surrounded by other people working. And that’s always been really important to me. The children would play amongst the trucks. I have a couple of great photos of them with hula hoops and bicycles and delivery men out with their carts all mixed together. No trees to speak of and a detox center a block away.

RAO: What is the story of the cherry trees that have since been planted on Langton Street?

JD: When I returned to photograph in the South of Market, now called SoMa, I noticed there were all these blooming cherry trees on Langton and I kind of rolled my eyes. “Oh, the ultimate gentrification.” And then I spoke to my former landlord, Tom, who was still living there. A great guy — he and his partner, Ted, had moved out from Saint Paul-Minneapolis in ’79 and bought the apartment house I was in. Tom told me that a young man, Ryan Hensley, was living in the first-floor apartment, the same one I’d lived in so long ago. He was in the terminal phase of AIDS and was to die within the year. This was 1992. He wanted to leave behind trees for the neighborhood, a legacy of sorts, though Tom said Ryan would not have thought in those terms; he was just wanting to make the world a better place. So the trees took on a passionate connection to urban life, they were there in honor of someone who lost their life to this horrible epidemic that came through San Francisco with such fury. I like getting to know a place so that the stories crack open the assumptions and allow a more complicated reading of the street.

RAO: In the ’70s and ’80s, you photographed pretty monumental changes in the neighborhood. For example, the building of the convention center. You were present as they were excavating this massive pit in the ground and you documented what that looked like; at the time it was this huge scar in the urban fabric. But you’ve also photographed intimate and quiet situations. One example that comes to mind is a kitchen in an apartment building that was ravaged in 1981 by a five-alarm fire: the burnt-out kitchen helped to tell a story about disinvestment in South of Market.

-

Remains of the July 10th five-alarm fire, Hallam Street, 1981 -

Workers leaving the Salesforce Lobby, 2016

JD: The urban planning strategy of the 1940s and ‘50s was to create areas of the city that would only have a certain kind of function. Rather than encourage mixed use it was decided that South of Market would be the industrial section, North of Market would be the financial district, out there would be the suburban homes, and over here would be the entertainment. And we’d have this magic thing called a freeway that would connect everybody — while cutting through and demolishing poor neighborhoods. Because of this master plan approach, investment in schools in the South of Market slowed, there were few grocery stores. Then the fire department was closed not far from where I lived. When this fire happened, it took a long time for the fire engines to show up from across town. It was said to be one of the biggest fires since the 1906 earthquake. The fire raged out of control and a hundred people lost their homes. I photographed it while it was burning. The next morning I managed to walk up the stairs of this burned out apartment with my view camera and I just started making pictures. The fire was another turning point for me, it made me think about the personal consequences of urban planning, perhaps unintended consequences, but consequences nonetheless.

The firefighters had found an amyl nitrate “factory” and rooms that looked like they had been used for S&M in the burned warehouse, so the chief of the department leaped on the assumption that the fire was caused by “homosexual activities.” And that story went out on the AP wire. Meanwhile, there was a group of gay men who owned a hotel nearby on Folsom Street: they opened their doors and let people who were displaced move into their hotel, they did fundraising, they brought food and supplies together, they did a really extensive outreach to try to help their neighbors. Ultimately the investigation of the fire determined that a disgruntled house painter who’d lost his job had gone into the storage area of the painting company and set rags on fire, and that’s what had started the whole thing. So you start to question the news media, when you see how people jump to conclusions and then those ideas become “fact.” They wanted to jump to that conclusion, because the gay community was seen as being the “homosexual scourge on San Francisco.” This is in 1980. You can see how far the politics have come in San Francisco from that era. Many of the artists in the area had photographed this fire and within a month they had organized an exhibition at 80 Langton Street, a non-profit gallery space. I remember seeing the neighbors come in and the firefighters pull up in front of the gallery with their big engines left idling, to see the show. That was a great neighborhood moment.

-

Saturday afternoon, Howard between 3rd and 4th Streets, 1981 -

Oracle Convention, Moscone Center, 2016

RAO: These narratives — or you might say, this fiction about blight or rundown conditions in the neighborhood — were used to justify urban renewal and the destruction of neighborhoods. Not only in South of Market, but in the Fillmore and in other parts of our city and cities across the country. The fire department on 7th Street in South of Market as well as other city services being closed contributed obviously to an overall sense and reality of hardship in the neighborhood; it sadly reinforced this justification that the neighborhood was less valuable, or the building stock less important and less valuable, so that you could turn over this part of the urban environment to a brand new use, to the detriment of those who actually already lived and worked there.

JD: The goal was to decimate the community so that they could create something that brings in this huge amount of money to the city in the form of the convention center, hotels, and museums. The intention was to build a cordon sanitaire around the site to keep out the local, low-income residents. This plan benefited the wealthy investors who purchased the land adjacent to this new development, and you see how the city’s been — well, made ready for globalization, I guess you could say. I’ve told you the story about the man from China who was walking next to me on the street just a couple years ago. I had something in my hand that said, “South of Market”; he asked me about it, and I told him how I’d lived there a long time and photographed the area, and he said, “Ah, boy, I love the convention center. That’s where my company was conceived one year, and it was born the next year at that same convention center.” The Moscone Center is this incredible place where people come from all over the world to meet and talk in person. So as much as I disdained it on a certain level, I also began to see its function and purpose. To the outside world, this center is a hub of interaction and commerce; to those who were displaced to make way for its construction, it was a death knell. To those who remained but are not part of this professional class, it has been a source of conflict. As San Francisco has expanded its global reach it has become a more affluent city for some. But it is very clear that that affluence is not benefiting everyone who lives in the neighborhood.

RAO: What about this narrative that artists contribute to dynamics of displacement, especially of those who are economically, politically, and socially disadvantaged; and maybe have less agency over where they can be, where they can work, how they earn their livings? What is the role of the artist and the arts institution in reifying and replicating capitalism? What is the relationship between the artist or the arts institution, and social, economic, and demographic transformation in a neighborhood?

JD: That is a complex question. There is a big difference between the actions of the individual artist and the presence of arts institutions. I don’t support this narrative of the artist-as-gentrifier, because in my mind it isn’t the artist who’s the gentrifier, it is the economic forces of developers that cause gentrification. Artists have flexibility and creativity and I’m not going to ascribe those things as negatives. Most of the artists that I ever interacted with were on the street, getting to know their community, working politically as well as doing their own artwork. Their presence may make an area seem more accessible to outsiders. But developers are gentrifiers, government zoning laws have aided gentrification, people with money who can manipulate the market, are the ones who create and benefit from gentrification.

RAO: I think there’s a couple ways that we could think of the figure of the artist: very typically someone without a lot of capital, who isn’t equipped with all of the things that developers, in this macroeconomic system that pushes things and people around, have. That’s one, you might say, defense of the artist. But then there’s also a very germane critique of the arts institution — whether that’s a physical place, or an idea. A museum or gallery exerts as a presence and a force, not only when it shows up, but continually over time. How does it sit within the context of a neighborhood? How does a museum or a gallery or an art center perpetuate the capitalistic system that is oppressive and effects displacement and gentrification? What kinds of ideas are brought up there, and reified within the institution or network of institutions, as perhaps we’ve seen in the “museum district,” which is sometimes how we describe a part of South of Market.

JD: Galleries and museums could be, obviously, tagged as gentrifying forces, if you look at them only in the context of vessels for making wealthy people wealthier and don’t look at them as places that hold culture or create experience for people in their own community. The wealth-making aspect of museums is being called into question, and rightly so. Who they serve needs to be made more inclusive, and those demands are coming from the bottom up. This idea has to be a part of every conversation with the funders and leaders of arts institutions. It’s a slow and difficult process, but the conversations are beginning to happen, in no small part because of the Black Lives Matter movement.

RAO: Well it’s true that executive leadership, governance boards, the portfolio of funders of these massive museums haven’t historically been inclusive or diverse in their representation. And so for me, the question is not about whether or not we need to dismantle the institution, but how we restructure leadership that shapes the vision and sets the agenda for the institution. And that’s where we see, especially at this moment, a lot of institutions struggling; organizations of every size and every stripe of social mission. There’s a real reckoning with the larger systems that have given rise to governance boards and leadership; money and capital are too often in the hands of a small brace of people who are not representative of the communities these very organizations are purported to serve and educate, enlighten, and inspire. And so, I think it does come from the bottom up, but it also needs to come from the top down.

JD: I would agree that there’s work that needs to be done to make our cultural institutions more responsive to the people who live around them. Indeed, their presence has altered the fabric of the neighborhood.

But the more important question would be where is government support for housing? Where is the middle-income housing? When will we realize housing is a right, not a privilege? There was a huge organizing effort by TODCO [Tenants and Owners Development Corporation] to replace the housing that was demolished to make room for the Moscone Center; five thousand people were displaced. But it was not nearly enough. Scarcity is at the root of the problem. We should be able to have both art and housing. Would that lessen the impact of gentrification?

RAO: The displacement is part of a much larger set of macroeconomic, tidal dynamics. How comes it that working-class Filipino families in the South of Market and elder Filipino men from a generation before were pushed out and pushed around? Indeed, the reason they were in the South of Market in the first place is because macroeconomic, global forces carried people around the world, creating the Filipino diaspora that we see today, and that I’m a part of.

I think there’s still an opportunity for us to think critically within this larger context about what the institution exhibits, whose work it exhibits, for whom it exhibits. And how the art museum reifies or challenges that larger system. There’s this narrative that the art institution has an explicit relationship with displacement in the neighborhoods that they are in, be it cultural dislocation, or literal displacement. Certainly, the image of South of Market urban renewal, with acres and acres of what were former houses and tenements and workplaces eliminated and replaced with this big civic, institutional use, are very much in line with the narrative of displacement in South of Market. How are the arts institutions, and the artists themselves, positioned within or outside of our capitalist economy? Part of the systems that channel those dynamics of displacement and rearrangement in cities?

JD: Back when I was doing the first project, I was well aware of the evidence that “the neighborhood was changing,” as my longtime neighbors would say. There was a divestment of factory work and the warehouses that supported those kinds of factories were no longer needed in the South of Market area, and artists began to take up residency in old factories. In the ’70s artists were moving into the neighborhood because it was an opportunity to have big space at a low cost. Were longtime community members being displaced by artists coming into warehouse space? Well, these were young and predominately white kids that were now walking around on the streets that hadn’t been there before; could they potentially make that neighborhood seem safer in the eyes of developers looking to gentrify? I just find that, at least in the way in which I experienced San Francisco, most of the artists came, lived in the warehouses for awhile, then couldn’t afford to stay or aged out of that lifestyle, and moved someplace else. And I think of it as just one of many migrations that came through the city.

The man who made my frames did buy an apartment house with money from his parents in the East Coast, and he did displace a number of Filipino workers from the apartment so he could renovate it. He told me he would welcome them to move back in, but by then the rent would have doubled. Money is the currency. If you have it, you get to do what you want. If you don’t, you don’t. And you can blame the individual players on a chessboard, but it’s the rules of the game that really need to be addressed. And you can say, “Artists shouldn’t have moved into those places.” So where should they have gone? It is all about housing shortage in the end.

RAO: Well, thinking in terms of systems rather than the individuals who inhabit and reify those systems — is there a way that the artist can show up in a place and interact with that neighborhood against the systemic pattern?

JD: You can either come in and become part of the community, partake in the local stores, bring yourself to the meetings, talk to your community, help to make the street a little nicer, be a good neighbor, and do your artwork; or you can come and you can seal yourself off and you can call the police if you see anything that seems dangerous, and you can complain about the noise and the factory around the corner, even though it was there before you got there.

That’s how it played out when developers started to renovate warehouse spaces into artists’ live-work lofts in the 1990s. The zoning laws that allowed this were trying to address the lack of options for artists housing. But the rent/cost on these newly developed “units” was so high that artists could not afford those spaces. We called them “lawyer lofts,” because those were the only people at the time who could afford them. They eventually became homes for the young tech entrepreneurs. That was not an answer for where artists are supposed to live.

-

Longtime neighbors, Langton at Folsom Street, 1981 -

Art Academy students waiting for van, New Montgomery Street, 2016

Many artists have migrated out of the city. So then they’re not around to really comment on the day-to-day essence of city living.

RAO: In the 1980s you collaborated with Laura Graham, your filmmaker roommate, to make a two-projector slideshow of images of your neighbors and included audio of their conversations around gentrification. With this exhibit you invited your neighbors into 80 Langton Street, an art space on their street that they had most likely rarely entered. And there was the exhibition of photos of local families and workers that you installed in the Ambush Bar, a gay bar where the walls usually had images of a more sexual nature. These events challenged conventional exhibition formats. More recently you installed large photos of the business owners on 6th Street in the windows of the CVS pharmacy on Market at 6th. You included interviews to introduce them to the public. To me, that says that’s Janet leaving her imprint on the neighborhood, in the same way that the neighborhood and the city imprints on your soul and your psyche.

JD: Yes, so true. I am obsessed with this neighborhood. Curious, since I have not lived here since about 1982.

RAO: What about art museums being machines within the larger machine of generating wealth?

JD: When they were doing the master plan for the convention center and the Yerba Buena Park, they were pretty explicit that they wanted to have hotels, restaurants, and museums around the perimeter so that the conventioneers would have amenities. Now we have the Contemporary Jewish Museum, the Museum of the African Diaspora, the Mexican Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art all in that museum corridor. Of all the things that happened there, that to me is the least negative, because they’re all working to foreground culture and to give a place for people to experience visual art. But it increases land value, there’s no question. One could critique whether or not the museums are doing a good job of being active in creating a successful representation of the community, and making their work accessible. The SFMOMA’s admission fee seems high. When that museum was first established on Van Ness in the Veteran’s Building, it was free. It was open late in the evenings, so that the workers could go after work to the museum. Now it closes at five o’clock, except one night a week. This flies in the face of the idea of it being a publicly accessible, cultural holding place for our thoughts and dreams. So there are many things you could critique. Is it helping the local populace? Is it a detriment or is it an asset? I’m going with, it’s an asset that needs to be significantly critiqued. I don’t want a world without visual art. And I want to see work from a wide demographic, from around the world and from right here.

RAO: And institutions of art and culture can help us explore complex issues of politics and identity, through having an experience of art. So they’re necessary, in my mind. There is currently a reckoning within these organizations, or any other kind of organization: they’re reconsidering how their leadership is structured and how representative it is; from the governance board up and down and across staff. That’s an important watershed moment for us. Sadly it had to take lots of tragedy as a forcing mechanism for our society to apply that critique more broadly and more deeply to all of our human institutions. We’ve started to see change and it’s accelerating even more.

RAO: There is this open question about the relationship between art and urban studies and planning. From your experience photographing this place in San Francisco that’s been heavily planned — over-planned, you might even say — developed and re-developed through many phases, what are your thoughts on how art might influence paradigms of planning or vice-versa? I bring this up thinking about this long tradition of photographers documenting the urban scene, the urban milieu, the vernacular, the quotidian conditions of the street. Eugène Atget is someone who you have studied and admired and has influenced you; Atget, as a flâneur, went out with an explicit agenda to document people in his urban surroundings. And then there are later figures in this lineage, like Ed Ruscha, based in Los Angeles, who was obsessed with the vernacular of this new urban physical environment that we were constructing rapidly. For example, his typological studies of apartment buildings and parking lots and gas stations. Over time, Ruscha also captured transition and change. I think of his big project THEN & NOW, where he literally photographs every single inch of both sides of Hollywood Boulevard; once decades ago and then again decades later he reprises that experiment. Surely there was some analysis that happened there, even if it was just purely visual analysis. If he wasn’t connecting it to the economics of housing or parking and transportation, he was still very much exploring relationships and revealing patterns of urban development.

JD: I’d like to know, as an urban planner, how do you experience these documents done by artists? How do you incorporate this information? As the photographer, my question is: what happens when my photographs enter the public conversation? For example: How did my South of Market work influence your understanding of that place?

RAO: When I look at your work, especially the photographs from the ’70s, the ’80s, what stands out to me as an urbanist is the sheer magnitude of physical transformation that South of Market underwent. You photographed the earth scraped clean of all that had been there before. All the buildings, all the lives, all of the relationships, all of the social fabric as well as the physical fabric, had been decimated and erased by that scar. The magnitude of transformation and erasure really stands out. Urban planners these days are very conscious of the destructive impacts of urban renewal on neighborhoods, in particular the social fabric of neighborhoods.

JD: Urban planning has evolved to be more aware of the existing community, rather than demolish and override what was there. The struggles around the building of the Moscone Center had a part to play in this evolution.

RAO: Absolutely. Contemporary urban planning philosophy and practice is nothing like it was in the mid-century, with its modernist figure in the ivory tower, exemplified by personalities like Robert Moses in New York. We understand the problematics of the modernist thesis that decimated neighborhoods by putting in freeways that would bring people from one part of the metropolis to another, with industry in one place and entertainment in another, and people living — if you were affluent enough — in some kind of bucolic suburbia. We’ve utterly dispensed with that philosophy, because there’s a lot of information that affirms how destructive it is. For me, some of the most influential documents of the destructive impact are works like yours.

JD: Even though I wasn’t operating as a social scientist with specific data-gathering strategies, the representation of a place and a people done from the point of view of an artist has its function outside of just being part of the language of fine art. I am reminded that records of cities have always been subjective. Early paintings and maps were certainly not literal representations of cities and now photographs have the appearance of fact but they too need to be framed with a subjective lens and seen in the context of their era. So the South of Market project and the work from SoMa Now are authored efforts that offer my view of a moment in the life of San Francisco.

Making a personal record has always been my intention. To have this conversation with you may be the apex of what I embarked upon in 1980. I know I wasn’t specifically instrumental in it, but my work does try to inform how we think about place. How do we describe a sense of place, and how do we make it live on beyond its own time? What are the salient moments you don’t want to miss? It’s like a time capsule. But I wouldn’t want it only to exist in the future. It should be part of the contemporary conversation.

RAO: We have in many other mediums that precede photography a dialectic between the image of the place and the actual thing. I think of Giambattista Piranesi in the eighteenth century; his picturesque approach to depicting the urban landscape and its organization and its monuments. Those works were tools that helped everyday people understand concepts about urban space and development and how human institutions exercise control over the shaping of that place and the allotment of land and therefore wealth. They were images with an agenda. Piranesi would take liberties, like making all the human figures in his pictures of Rome extra tiny, as to make the surviving ruins of Roman monuments seem that much more grandiose. But there isn’t that same literalness of what photography can capture. We expect a kind of literality about what we ingest and how we apply the information we’re receiving from a photographic image to our understanding of the world or how we fit in.

JD: Always with the caveat that nothing’s literal and there’s a choice of lens and an interpretation and it’s a medium that can be managed in many ways. But still, street photography is at the heart of what I’ve always practiced, whether I am indoors or out, I am a fairly silent observer.

I’m thinking, also, about Atget, and how he not only photographed the grand views and the elegant places of Paris, but he also went to the suburbs around the back side of the city, and he photographed people living in little tent carts; chimney sweeps and others who weren’t as well off. He really worked to create a full document of a city suffering from Haussmann’s major urban renewal project of the mid 1800s. I felt very committed to this idea of making a record with my photographs of South of Market in the 80s and now.

Conversations like the one we’re having allow for some kind of acknowledgment in the overlap between our professions. I’m on the street, just looking. And that is such a privileged position, to stand still when everyone’s rushing around, and observe how people are experiencing that place. Who’s sleeping on the sidewalk and who’s dropping their pricey car off with the valet.

RAO: Well certainly the figure of the flâneur, which I think we both identify with very much, is a part of what an urban planner is. One of our ultimate flâneurs, William H. Whyte, pioneered a methodology for observing and studying in a pretty rigorous manner the occupancy of our public places. He wanted to impact the way that we design and build planned public spaces. And of course he leveraged photography, alongside many other methodologies, as a way of documenting what was happening.

RAO: Does the visual language, the aesthetic construction of the photograph, have an impact on its function, and vice-versa? In a visual analysis of your photos, comparing one era to another in this place South of Market — you capture a lot of advertisements, which themselves are often pieces of photography or visual presentations of the future urban landscape, or the future office building, or the future high rise residential building.

Space and time get compressed; or the representation of them do, in the way renderings of future buildings are presented… the advertisement of the future building’s interior is so huge as you’re standing next to it on the sidewalk. You’re almost inside of it, occupying that future place that has yet to be built. We’re exploring time and your experience and relationship to the neighborhood over time.

JD: I have puzzled over how to make photographs of a city for a long time. It is a big undertaking and there is no one correct way to do it. I approach the image-making process with the idea to make specific photographs that help me to both describe and discover what I am seeing. I am working to connect the literal document that is so much a part of photography with the poetic sensibility, so that the viewer can enter the images from many different angles.

RAO: There’s a visual irony in photographing an advertisement at street level that depicts a sweeping city view from the top of a skyscraper. So you’re looking at the future cityscape while you’re standing on the sidewalk. That differential in scale — in time and space — is so striking to me. There’s a lot of layering, there’s a lot of peering into the past and peering into reimagined urban futures.

RAO: On the left we have a photograph from the 1970s, seen from the north looking south. In the foreground is the Aronson Building, in the background you can see the earth scraped clean in preparation for the construction of the gardens and the Convention Center. There’s this very interesting double, triple layering of urban space and function in these two photographs. The architectural features of the Aronson building are pretty unmistakable. From whatever angle in whatever era you’re looking, it’s the pivot around which all of this development has emerged.

JD: The Aronson building was under renovation and the photograph that I made of it in 2017 from the Yerba Buena Gardens included a depiction of the SFMOMA in the foreground. You could never actually see those two things from that same point of view in real time, geographically it wasn’t possible; I pushed those ideas together, that this renovation of this building is related to the museum, which is just next door. Space and time were being compressed — what was really happening versus what they were hoping to have happen. So there’s a kind of subtext to the fact that we think we’re living in three-dimensional space, but in fact we’re bombarded by all these other layers and perspectives that we constantly have to narrate, to translate, or incorporate into our understanding of that place. It’s a pretty complicated system that we bring with us when we pop into a city. How do you read the city? You have reflections, you have signs, you have construction; you have potential future, you have representation of the past, and they’re all happening at the same time. One of the things that’s so exciting about this photo is the fact that you’re standing in one place that has both this deep history and this incredible future, as yet not fully realized. The past is partly disintegrated and your present moment is all you’ve got.

-

Jean Decottignies, Jean’s Auto Body Specialists, 1264 Folsom Street, 1982 -

Anthony Heffernan, mechanic at Scoot, 1077 Howard Street, 2019

RAO: I love the posture of both subjects in these photographs. They’re at their jobs, doing important work.

A lot of what you photographed in South of Market over the last four decades are places of labor and production, from boutique office spaces to back room office spaces, to machine shops and maintenance facilities… from the early ’80s and again in the 2000s, you get a real peek into the way these places are inhabited. To the average person walking through, who doesn’t have too much connection to the neighborhood, a lot of industrial landscapes that were so much a part of South of Market can be illegible and mysterious: what happens in those office buildings and converted warehouses? Your work is a telescope, showing us who’s living and breathing and making and working in these places.

JD: When I went back in 2011, after having not really photographed this neighborhood seriously since ’86, I started by looking at it from street level. The first impression I recall was of doorbells and buzzers and locks and gates and I soon realized that I didn’t have access to much of anything; if I want to get in anywhere, I need to know somebody. For the past ten years I have been working on establishing connections with people who currently live and work in SoMa so that I can get inside and make photographs of the way people work and live here now.

-

Pat serving coffee at the Gordon Cafe, 7th at Mission Street, 1980 -

Chipotle Lunch Counter, New Montgomery Street, 2013

RAO: If you were to compare your current approach to photographing in South of Market versus earlier on, would you say there’s more intention these days in trying to seek out certain situations? My impression — and please correct me if I’m wrong — is that in the ’80s it might have been more exploring and wandering around the neighborhood without necessarily having this agenda to expose what’s happening.

JD: I’m a lot more knowledgeable now than I was then. The current work is better informed from a factual perspective and because of my long relationship with this place and because I have access to so much more information now. Teaching visual studies at the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley also widened my knowledge of city planning, just through osmosis!

But I want to clarify: in the 1980s I definitely had the intention of building a story about what was going on in the South of Market in relation to the new convention center and the impact it would have on the surrounding neighborhood. The first project is based on my intimate experience of the area, it is infused with first-hand knowledge as well as my understanding of the political forces at play in urban renewal and gentrification. My current work also grows from a certain amount of wandering around, observing the interactions on the street and the ways the built environment is changing. I am once more interviewing people and I think these interviews, along with my background research and photographs, will offer a way to see, not just how San Francisco has changed in thirty-plus years, but also how city life in general has evolved.

There’s a lot of power in the first project, South of Market (Mack, 2013), because of the fact that it is from another era; those photographs allow you to go places that no longer exist. Hopefully SoMa Now will eventually carry this same weight and be a point of reference for traveling back to 2020.

RAO: What a wonderful experience to set up for one’s self, to revisit the same physical place even though socially and economically a lot of the dimensions are different. You as an artist, as a human being, are different — what motivated you to come back?

JD: I was getting started on the production of my first book, South of Market. As I was going through my 4×5 negatives from the 1980s I thought, I’ll go back and just see what it looks like now. I took copies of the photographs and I stood where they had been made and thought, OK I’ll take that photograph again. But immediately I knew that wasn’t what it was about. In 2010 the new high-rises and apartment buildings had not yet been built. What was different was the culture and the economy. At that moment, SoMa was just on the edge of becoming what we think of now. The conversations I overheard while I was photographing on the streets were most likely to be among young male tech engineers/entrepreneurs from all over the world who were excitedly talking about their most recent projects. A few years later young, mostly female workers on lunch breaks were discussing social media marketing and issues around HR, or People Relations as this position is now titled. I could sense how the technology business was taking hold. I felt that people who were coming to San Francisco weren’t coming because they needed the progressive culture of San Francisco; they just came here because they knew this was where the technology job was or this was where the venture capital was. And then as soon as they got their money, they’d be gone. I’m not certain this is entirely the case because I do see that the ethos of San Francisco, its progressive nature, has had an impact on some aspects of the technology revolution.

RAO: We’re certainly at a huge point of inflection, a profound process of transformation in this city, in cities across the world. I often think about how we could take this opportunity to set intentions about what that future could and should look like for us, how we can leverage the moment to launch ourselves in that direction. Or we could find ourselves in a transformed future state that’s the consequence of reactionary, panicked decisions we make with a short-term mindset created by the many existential anxieties we’re all feeling around this global pandemic and what it means for public life and for civics and our economies and our families — that is one that I get really, really anxious about. It really is our chance to reboot and rewire all of these structural and historical inequalities that have led us to this present moment… our chance to rethink and undo those, rather than let this public health and this social, this psychological crisis that’s unfolding, amplify and deepen those inequalities.

JD: I bet it’s going to be some of both. If you look back, in so many ways things are so much better than they used to be. And then there are those areas in which we have failed miserably. But it’s important to recall the distance that we have come.

-

Janet Delaney in her darkroom at 62 Langton Street, 1981 -

Stephanie Delaney Sannazzaro, Avalon Apartments, 2015

JD: I have a strong feeling about the idea of continuity over time; when my niece became part of the story, well, that was a powerful moment for me. She is now the age I was when I lived in the South of Market. And here she is living in SoMa now. That image of me in my darkroom on Langton Street, a place I built for myself to fit what I wanted to do and to be, compared to this image of Stephanie with her laptop, which is her primary connection to her work and her world, sitting in a lounge space in a corporate apartment complex (complete with climbing wall ). It feels as if she is sitting in a staged environment, as opposed to being in a place that is her own. (I’ll add here that she and her husband have since moved to a more homey apartment in Berkeley.)

There is no one moment where everything in a city is finished. Cities grow, decay, begin again. Some aspects of city living change slowly and others rapidly. San Francisco was established at about the same time that photography was becoming widely used, the 1850s. So the city has a long photographic record. My first introduction to cities and to photography was through the photographs of Paris made by Atget at the turn of the twentieth century and through the images by Berenice Abbot of New York City in the 1920s and ‘30s. These clear observations have kept those places and that time alive. Hopefully my images of San Francisco will do something similar for our own sense of place and time.

RAO: Would it be fair to say that your photographs of SoMa and the Mission, which you also extensively photographed, are love letters to those neighborhoods and to San Francisco?

JD: If you’re in a relationship with a place, just like any relationship — love it unconditionally and critique it, you know, viciously. [Laughter] Because we’re always trying to get a little better, right? That doesn’t mean for any lack of love, it just means that I’m passionate about keeping an eye on it.