Party of One

Eliana, 2018, watercolor, 22”x15”; by Michelle Thomas

The art history I studied in early twenty-first century North America was largely devoid of faces like mine. Historical images appeared in a National Geographic sense, in an ethnographic context — making only the occasional cameo, usually in a documentarian’s catalogue of conquered peoples and places. Artists with faces like mine were presented as artisans, lacking individual whim or whimsy, marching to the tune of a cultural collective consciousness. Conjure up a reality in which text after text represents the art of Europe in a single chapter, introduced with a Fragonard, labelled with a shrug: Eighteenth century, Central Europe, painting on fabric.

I rallied against the exclusion of people of color from the canon, taking Asian art history classes, studying current art of the African diaspora and architectural commissions of the Mughal emperors, begging instructors for independent-study courses on subjects not offered, making pilgrimages to design districts in Hong Kong, Singapore, Mumbai, Dubai. More, more, more, a hungry clawing for all that had been withheld.

I made lots of art, culminating in a senior project: a huge self-portrait in the style of Diego Rivera, carrying on my back a legion of Indian stereotypes. Indiahibition: A billion chips on my shoulder.

Indiahibition: A billion chips on my shoulder, 2005, wax and pigment on wood, 78”x41”x3”; by Michelle Thomas

I have always lived in the United States. I have no geographic reason for my compulsive attachment to India and have greater expertise on Chicago, the Midwest, the Northern Hemisphere (I did grow up watching Bollywood music programs on rainy Saturday mornings, convinced that if only my parents had raised me in India my life would have been fine, better than fine — spectacular! Eventful! Full of dancing and coquetry; dancing and coquetry on roller skates at snazzy Marine Drive rooftop parties, dancing and song and coquetry in the snowy Himalayan foothills.). On what authority could I speak on India? By the authority conferred on me by strangers demanding authentic recipes, shopping tips, exotic tall tales of my presumed past; they noted my “foreign accent,” commended my “surprising” command of the English language. The strangers obviously and consistently drew from two expectations: as Robyn Wiegman writes in “Race, Ethnicity and Film,” “For non-white females, the stereotype oscillates between a nurturing, de-sexualized, loyal figure and a woman of exotic, loose, and dangerous sexuality.” To Wiegman’s examples, which include Mammy in Gone With the Wind and Epiphany Proudfoot in Angel Heart, I would add more current figures, portrayed by the likes of Mindy Kaling and Sofía Vergara. I succumbed to these artificial personae, enduring an eating-me-alive bitterness and shuttling for much of my life between anxiety and melancholy. Defined in youth by racial marginality, my identity became tied up first in being an other, dissecting this status constantly, and then devoting myself to advocacy as an artist and a teacher, ever so hoping to alleviate the discomfort of those othered — myself included.

My portfolio remains overwhelmingly figurative, the urge to present coming from an urge to physically represent those obscured by the historical narrative imposed on me, those rendered invisible by the social and media messages imposed on me. I have aimed to illustrate my reality (full of multifaceted people of every color) and to establish a system on my own terms and according to my logic, making up for lost centuries by painting my face again and again and again.

Meneka, 2019, watercolor, 30”x22”; by Michelle Thomas

This work is not complete. When, for example, I seek representation of my racial demographic in the collection of SFMOMA, the largest museum of modern and contemporary art on the West Coast, my chosen place of work in my chosen home city, I come away disappointed. As of 2019, Asians living in Asia alone account for sixty percent of the world’s population, and in San Francisco, thirty-five percent of the population reported their race as Asian. I spent a recent weekend scouring the SFMOMA database, inputting myriad search term permutations to locate artists of my demographic (in the broadest sense, including artists of West Asian heritage and artists of the Asian diaspora): according to my research, of the six thousand artists in the collection, 109 (1.8 percent) are identified as Asian or of the diaspora; from this group, nine (.15 percent) as Indian or of the diaspora. So I continue to make representations of those underrepresented I know and love so well: a family sitting at an airport, site of our joyous reunions and our aching departures; a series of paintings reflecting the identity crisis, crises, of the immigrant’s child; a master’s thesis on how to read the production of artists who are minorities in the US (in short: with the same lens one would use to assess any artist of the Western canon — artist as independent creator rather than ethnographic object); portraits upon portraits of girls like my sister, bold, fiercely resilient, never the victim. I leave nothing to viewer interpretation. I am ever centering, ever documenting, ever chronicling. I am ever representing.

From left to right: Noor, 2018, watercolor, 30”x22”; Aelius, 2018, watercolor, 30”x22”; Helene, 2017, watercolor, 30”x22”; all by Michelle Thomas

Enough. It is such hard, emotionally taxing work providing didactic context for the mainstream viewer (ever) looming over my consciousness, trying so desperately to explain a multifaceted upbringing and identity to a firmly alien audience. It is as if I have chosen a love lacking in natural awareness and empathy; he needs me to spell out what I am feeling, explain my reactions to offense, over and over again. I see in his face, he does not completely grasp me. He will never feel that he can read me, my motivations, what happens next. He tells me, after the novelty has worn off, after lots of crying and failed attempts at communication, that I remain elusive, that he doesn’t know me.

I never gave myself the chance to simply mark my existence — without representing people of color or Indians, or Indian Americans, or women, or early millennials, or artists, or educators, or Chicagoans, or Christians with roots in Kerala, countless millions of us with the incongruous surname Thomas. Yet I can’t carry everyone anymore. And I’m fed up explaining myself to strangers — But where are you really from? — labelling myself for easy categorization, digestion, discrimination.

I feel alone at my intersection. As a result, I expend great energy on every interaction, identifying common ground, usually no more than an iota, clutching it, cultivating this point of entry with hopes for mutual empathy and love. I do everything possible to make others comfortable in my foreign-seeming presence, urgently emphasizing our shared humanity: I overshare and expose my vulnerabilities, I laugh constantly. I dole out bountiful dollops of interest and encouragement for every little victory of colleagues, friends, even when I myself am crushingly depressed. I listen to stories about spouses, children, pets. I do not have a spouse, a child, a pet.

I long held a fantasy: might I shut out the world, make art that can take off its bra and relax, that is quiet and simple, that doesn’t have to code switch? And then — the world shut down.

Even before we were sheltering in place, I had been quietly detaching from draining social obligations. Now, in extended seclusion, I feel my time has finally come. I am alone at last, released from the burden of representation, at ease and without obligation. I feel like my truest self, the self I was as a prepubescent ten-year-old, watching Bollywood MTV in fascination, humming along while understanding not a lick of Hindi, snacking on Life cereal from the box. In extended physical solitude, I’m not performing the deference expected of me as a feminine, mild-mannered, ethnically ambiguous woman. Removed from the daily presence of the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker telling me who they think I am all day long, I have clarity on who I am and what I can tolerate and how I want to spend my days. I’m gardening, spoiling my plants with attention. I’m stretching and activating my full length in the morning, taking long walks in the afternoon. I’m finally getting a handle on piano pieces I’ve been poking at for years. I’m studying ancient prophecies and devouring the latest how-to bestsellers. I am spending long hours on the phone interviewing my oldest relatives and reading into the night, researching our history. I am chronicling the journeys of my parents, their parents and grandparents, with an intended audience of one: my sister. Articulation for or validation from anyone beyond is secondary, even irrelevant. It is enough that someone who sees and knows and must love me keeps the record that we were here, I was here.

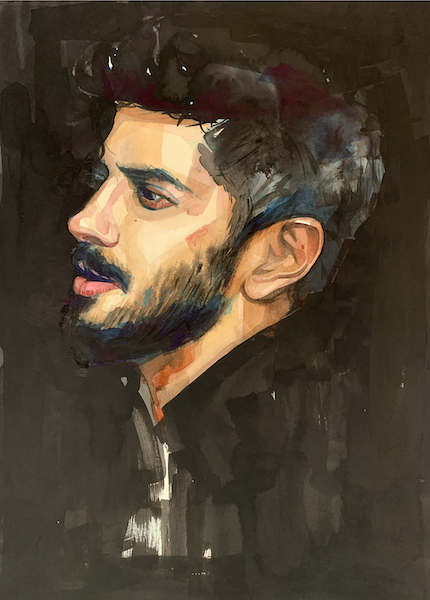

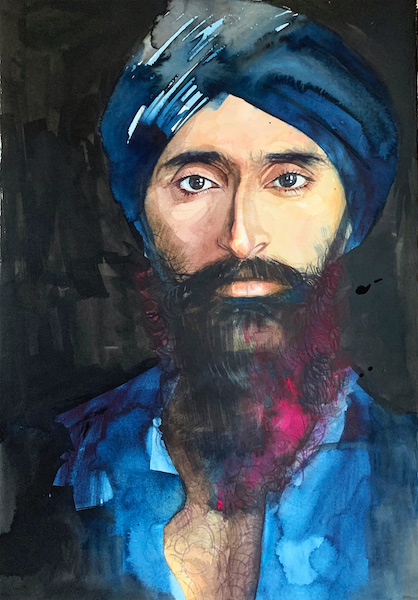

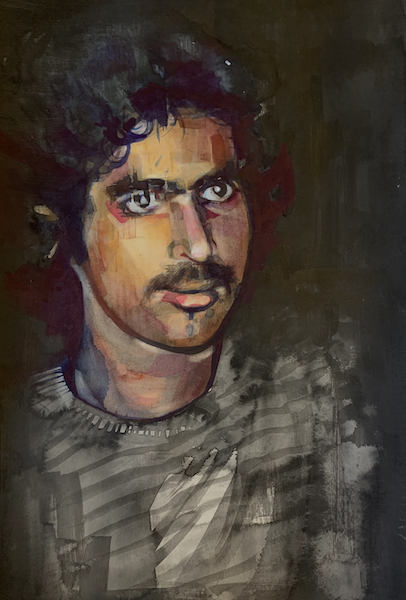

I’m painting a whole new gang, perfect companions. They are gentle, they do not argue with me about where I’m really from. They have no discernible past, offering few clues as to their background, time, place, future. They give no explanation for their attitude, the texture of their hair, their accent, their religion, their height, their weight, their taste in music, their education, their expectations, their handwriting, their racial ambiguity, the contents of their suitcase, their resting face. My subjects are former ethnographic objects, at rest. They are alone, deliciously alone, as I am when I close the door, take off my shoes, find a sunlit spot, sit in perfect silence. In the world, my existence is political. When I close the door to a political conversation, my existence is my existence.

From left to right: Translations: Habakkuk, 2020, watercolor, 22”x15”; Translations: Danyal, 2020, watercolor, 22”x15”; Translations: Yohannan, 2020, watercolor, 22”x15”; all by Michelle Thomas

I give myself permission to be. I am not the representative of the BIPOC portion of a racial binary supposedly unified along a party line. When I weigh in on current issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion at SFMOMA, I preemptively state that I am offering an opinion rooted in a nuanced individual experience. This time of social crisis has moved the museum to reckon with the past, refreshing policy and systems and reconsidering accessions. Of course, I say, the museum must collect more work by artists from underrepresented groups — but we should not strive merely to hit representational quotas. How much better to reflect on and redefine biased notions of excellence, prizing aesthetic and ideological variety. I am not the voice of a demographic. I do not claim to speak for anyone more than myself: my perspective, party of one, matters. I am at the table, not to help hit a metric, but to help figure out ways each one of us might better thrive.