A Memory, A Relic

The very elements that made Jackie Sibblies Drury’s We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Sudwestafrika, Between the Years 1884–1915 (henceforth referred to as We are Proud to Present…) amusing also made it troubling. The play, a play about the making of a play, shows six actors attempting to make sense of and present their presentation about the 1904–1908 Herero Genocide. The attempts to recall the timeline of the genocide and parse out what can and should be shared with the audience lead to a deterioration of the production and a traumatizing (for one of the Black actors in particular) end. The divergence in the actors’ creative priorities — do we focus on the German story or the Herero story? — is reminiscent of the messiness of collective remembrance and the way that who you are largely informs exactly what you are interested in remembering. Central to acknowledgement, after all, is legibility; and legibility, after all, is a kind of assimilation.

What does it mean to tell a people’s story, a story of genocide, via the humanized perpetrator? It’s the same cowardly act that compels remembrance and recompense through begrudging and self-flagellating guilt and penance (coupled often with absolution) as opposed to earnest and radical accounting 1 for wrongdoing. Consider how badly we fail at apologizing: the primacy of the recitation of “I’m sorry” supersedes behavioral change or potential for a harmed person to dictate terms of reparation. Emphasizing the interaction between a German man and his wife feels like an allusion to how recollections of phenomena favor an obsession with perpetrator profiling and psychology over interior processes and reactions of the harmed. “There might be some distant representation of African bodies … but the love is foregrounded” reads one italicized stage direction. Blacks occupy space, but they don’t have interiority.

A predictable trivialization of African pain comes from predictable white racism and unfortunate diasporic Black disconnect. It is telling how the performance of African subservience quickly becomes a reproduced caricature of American chattel enslavement — that’s the paradigmatic relationship of Blackness and subjugation, a “specialness [that] is a perversely strange outcome of being at the center of empire” as Rinaldo Walcott put it. I read this as deliberate on Sibblies Drury’s part; a Zimbabwean friend of mine was less convinced.

At one point, the actors attribute the difficulty in creating a Herero story to a lack of material evidence of the genocide committed: not a denial that there was a genocide, but an absence of letters and images and revealing documents beyond German ones. “I’m not saying the genocide was made up,” says Actor 1. “I’m just saying we don’t have physical evidence.” The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but how can one actually claim that there is no evidence? Why is there “no evidence”? Why is this horror not worth remembering? When I was in the National Archives in Namibia, there was a note on a number of genocide-era documents explaining that they had been destroyed, stolen, or sent back to Germany; perpetrators are often careful to ensure they leave little trace of criminal execution in their wake — save, of course, a trail of corpses.

The genocide of the Herero and Nama was not a rehearsal, as it is often described, but it was a structuring: a genocide that served as bureaucratic preparation, a turning of colonial necrotechnologies of control and population management onto Europe. The genocide is unnamed and relatively unacknowledged because it is meant to be forgotten and that is why the actors, too, struggled to remember. The Herero deaths are ones to be “elided as history is canonized.” Sibblies Drury writes:

That death is stripped of its humanity, which seems to be, if not a fate worse than death, perhaps a death worse than death. And perhaps, in turn, allowing that elided death to remain unimagined makes us a bit less human.

There is evidence of the genocide in South West Africa. There are photographs of the Shark Island concentration camp, casual postcards illustrating German complicity, a recently dismissed class action lawsuit in a New York federal court. There are not widely disseminated Indigenous testimonials of this twentieth century campaign because it is not ever essential for Africans to speak for themselves. But there are skulls. There are skulls in Germany, in the United States (the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan), South Africa, and in other places. When I went to Namibia last year, another group of skull remains was being returned as a part of a process that has been unsatisfactory to many Herero descendants of genocide survivors. The evidence of wrongdoing is present in scientific methods, epistemes, and discourses. The concentration camp was a means of bone collecting: the living were forced to scrape clean the skeletons of the dead for sale and circulation in Europe. They were for eugenicist study. The archive is evidence.

I was told that in traditional Nama culture, there is a pre-Christian supreme being called Tsui-//goab. Upon death, one returns to this being; as the human body emerges from the earth and soil, it must return to that place. The spirits of the deceased cannot rest without proper burial: some of these skulls were obtained through grave-robbing, an ostensible disruption of ancestralization processes. Orlando Patterson describes natal alienation as one of the three aspects of chattel slavery: it is a detachment of a person or people from their kin, “the loss of ties of birth in both ascending and descending generations.” 2 Cultural genocide — this social death, this repeated posthumous killing, the display and/or use of these bones for Western edification — is the evidence.

In War Primer, there’s a photograph of a German woman standing in the rubble of what used to be her home; it was destroyed in an air raid by the British Royal Air Force. About the image, Bertolt Brecht writes:

Stop searching woman: you will never find them.

But, woman, don’t accept that Fate is to blame.

Those murky forces, woman, that torment you

Have each of them a face, address, and name. 3

When dealing with intractable loss, we can and must name our killers and our dead, and we must treasure those who lived.

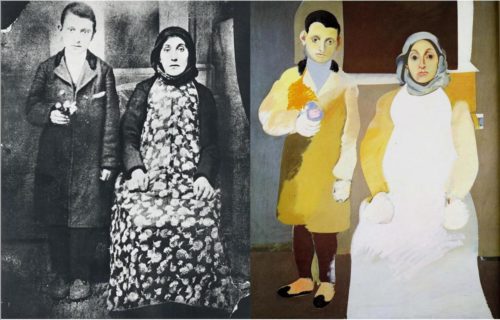

In the preface of Nazik Armenakyan’s Survivors (2015), philosopher Marc Nichanian describes the image, the survivor image, as a relic. The Catastrophe 4 5is immortalized in a particular way through Armenakyan’s portraits of survivorship. He writes that one “can narrate these things and bear witness for them. But that is not the way in which the Catastrophe will ever appear. This is not how it will be captured. Unless the picture shows the image as a relic. That is how the face of the survivor is seen as the face of a survivor.” If the re-conveying and re-articulating and re-litigating of trauma for purposes of acknowledgement and recognition is a trauma in itself, how do we craft Testimony from testimony? How would we immortalize a moment or a memory “except to show the picture as a relic and turn each face into its own image, thus transforming it into the face of a real survivor, rather than the face of just anybody…?” “Relic” in ancient Armenian is neshkar, he explains: stripped of contemporary theological connotations, it simply refers to a remnant. Nichanian invokes Armenian writer Hagop Oshagan and his own use of the word neshkareal in reference to himself and other Armenian intellectuals whose arrests and deportations marked the beginning of the genocide — they were “‘transformed into relics,’ but also ‘remain as relics in our memories.’” The survivor is a remnant, i.e. “what remains after the death of the witness, thus as a relic” (or, further, one “who had ‘returned from death'”).

This painting is in the genocide museum in Yerevan, Tsitsernakaberd. I regrettably forget the painter, but it is called “The Golgotha of Armenian Intellectuals.” “Golgotha” translates to “skull” in Latin and Aramaic, in Matthew and Mark’s gospels, “Κρανίου Τόπος Kraníou Tópos” translates to “place of the skull”; it refers to the hill just outside of Jerusalem where Jesus was crucified.

Nichanian describes an Armenian adaptation of the Roman word pictura or “picture”: kendanagir refers to a drawn portrait of a person, which was kept in the house and played the role of the relic. It reminds me of the sad paintings of Arshile Gorky, who painted over and over again the scenes and ephemera that he could remember of his childhood home near Lake Van, which he and his mother and sisters had to flee because of the genocide. I found a book of English-translated letters Gorky had written to his sister one afternoon in Vernissage Market in Yerevan, which I later realized were probably fakes. I remember reading in that book (or maybe somewhere else) that the reason he did not finish his famous painting, The Artist and His Mother (1926–36) — based on the only surviving photograph he had from his childhood — was because he could not remember what her hands looked like; his mother, Shushan, starved to death in 1919 when he was a teenager. Real or not, I transposed the thread of devastating nostalgia and emptiness and anger onto his paintings. Is the canon’s difficulty in categorizing his work a reflection of the impossibly difficult task of translating the image-as-relic through incongruous cultural frames?

I learnt about Nazik’s work through an Armenian-American filmmaker friend. I met her for an interview on May 2 of this year, and I remember spending most of our conversation swallowing down the tears that kept gathering in my throat. She described to me how this project was a processual one, that it started around the time her father was dying of cancer; he encouraged her to finish it. Immortalizing these survivors was her therapy, a reckoning with his coming death and mortality more generally. There’s a way that the Catastrophe is so unfathomable, its history becomes enmeshed in an ethos of superhumanism: whether the super badness of the perpetrators or the super heroism of those who resisted (like those at Musa Dagh and in other locations) and endured, those who survived and did not survive. We sometimes forget that the people we make our heroes do not live forever. And so this book, she told me, was to remind us of their mortality. In fact, the book begins with an image of Ashken Avetisyan surrounded by her two sons and with a picture of herself in her younger years resting nearby: she had died shortly before Nazik’s arrival.

Ashken Avetisyan, Atar village/Bitlis vilayet, born 1907. The photograph, per the book’s caption, was taken in 2009.

Each portrait follows roughly the same template. In the image itself is a survivor of the genocide; below the image is the year the portrait was taken, their place of birth, and their year of birth. At the end of the book are testimonies from each subject, excerpts from the conversations Nazik had with the photographed, sometimes over a period of many weeks or months and many visits. She hoped to understand these elders holistically as not just people who survived a genocide, but as people who also survived so many years of life afterwards. The people she photographed were, overwhelmingly, enthusiastic about sharing their stories and eager to be photographed. Nazik told me that in addition to describing how they survived or lost loved ones or lived after the genocide, a number of them also described Stalinist repression of their genocide experiences: people were not allowed to talk about it, and so they would speak in Turkish or Kurdish so their children could not understand.

She gave me one of her books after the interview, so I could get more familiar with her work. It’s a large hardcover book with text in both English and Armenian. Some days, the photographs are buoying. I look at them and I feel the hope of her project. I feel the responsibility for bridging past and present that animated her, a humanization of subject that pulls them from the brink of interchangeability that can come when atrocities are intended to be universalized — when trauma is flattened into moralization 6. Other days, I really can’t bear to open it. I’m confronted by the cumbersome weight of the memory of genocide and the shared responsibility of ensuring we never allow our dead to die the final death that happens when we forget [how] to and cease to speak their names; I’m overwhelmed by the confrontation of the survivor as a relic and the weightiness of crafting testimony that forces us to confront the full ontology of survivorship. The relief, the guilt, the gratitude, the anger and contempt, the sadness, the nightmares, the terror, the terrifying clarity of memory.

Nazik’s images are human, but James Estrin was correct in describing them as “reminiscent of Christian Orthodox icons in their directness.” The portraits are unnerving because of how their subjects look at the camera (some do not: they have their eyes closed or are looking into space or at someone else). We are gazing at them and they are returning our gaze. They are old, they have lived many years, and they will die soon, but still they are piercing [through] us with their lives. There are no passive subjects here, and in the way they are photographed, they will live forever. The Turkish denialist line about the contested archive (i.e. definitive proof of Ottoman genocidal wrongdoing) is not to be entertained: these images, this Testimony, is evidence.

- This is not to invent a new kind of accountability by using “radical” as prefix per trend (e.g. “radical hospitality,” “radical empathy,” etc.), but to couple the word “accountability” with the word “radical,” which refers to the fundamental nature or root of a thing. A “radical accounting for” speaks to what Michael Rothberg describes as a “multidirectionality” that doesn’t compel one to historicize using a frame of Shoah uniqueness and allows for recognition of the “significance of both genocidal imperialism and the totalitarian Holocaust.” See: Hannah Arendt and the Negro Question (2014) by Kathryn Sophia Belle, and Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (2009).

- See: Orlando Patterson’s Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (1982).

- See Brecht’s War Primer (published in 2017).

- From Khatchig Mouradian’s “Explaining the Unexplainable: Terminology Employed by Armenian Media” (2006): In the editorials under study, the term most commonly and consistently used from the 1920s to the present is Yeghern (Crime/Catastrophe), or variants like Medz Yeghern (Great Crime) and Abrilian Yeghern (the April Crime). Other terms include Hayasbanutyun (Armenocide), Medz Voghperkutyun (Great Tragedy), Medz Vogchagez (Great Holocaust), Medz Nahadagutyun (Great Martyrdom), Aghed (Catastrophe), Medz Nakhjir and Medz Sbant (both, Great Massacre), Medz Potorig (Great Storm), Sev Vojir (Black Crime) and, after 1948, Tseghasbanutyun (Genocide), or variants like Haygagan Tseghasbanutyun and Hayots Tseghasbanutyun (both, Armenian Genocide).

- From Harutyun Marutyan's "Trauma and Identity: On Structural Particularities of Armenian Genocide and Jewish Holocaust" (2006): The translation of 'holocaust' in Armenian, 'voghjakizum,' manifests certain ambiguity: the first part of the term, 'voghj,' has the meanings 'all' and 'alive,' while 'kizum' means 'burning.' Thus the term can also be understood as 'burning alive'...While historians are well aware of the facts about Armenians having been burnt alive by the Turks, ordinary citizens have this memory mainly as a result of literary works. Of these, the most vivid is a poem by Siamanto (Atom Yarjanian), a Western Armenian writer and a victim of the Genocide, called 'The Dance,' which, long ago, was included in Armenian school curricula. The poem describes an episode from the 1909 massacres in Cilicia, when Turks stripped Armenian women and made them dance, and then poured 'a barrel of oil' over the naked bodies to burn them alive. It is in this poem that the expression 'O, human justice, let me spit at your forehead' was first used.

- See: John Mowitt's "Trauma Envy" (2000).

Comments (5)

Outright massacres and murders of Namibia’s people by the Germans between 1904 and 1908 included not only Herero and Nama but also San and Damara. Thousands of Herero and Nama were confined to concentration camps where they experienced horrific living conditions, including lack of food, water, and medical attention. Others were forced into slave labor, building roads and railways, and working in mines and on German farms and ranches.

The genocide against the Herero and Nama had several phases. The first of these involved massacres of both combatants and non-combatants. The second phase consisted of the establishment of a cordon in the Omaheke region and hunting down and dispatching Herero refugees from the Battle of Omahakari. The third phase was the implementation of a scorched-earth policy aimed at destroying the livelihoods of the Herero and Nama; not only destroying homes, corrals, and sacred sites, but also capturing or destroying Herero and Nama cattle, goats and sheep and burning their crops.

The wounds inflicted by the great massacre of 60,000 Herero and 10,000 Namas in the former colony of Southwest Africa have yet to heal. Added to the concentration camps and slave labor, are the scars from the exhibition of human remains in museums and the manipulation for racist scientific theories. After a century of denial, the governments of both countries agreed to compensation of 1.1 billion euros over a period of 30 years. However, the descendants of the victims do not feel that their demands are heard.

The genocide against the Herero and Nama had several phases. The first of these involved massacres of both combatants and non-combatants. The second phase consisted of the establishment of a cordon in the Omaheke region and hunting down and dispatching Herero refugees from the Battle of Omahakari. The third phase was the implementation of a scorched-earth policy aimed at destroying the livelihoods of the Herero and Nama; not only destroying homes, corrals, and sacred sites, but also capturing or destroying Herero and Nama cattle, goats and sheep and burning their crops.

The period between the cessation of formal war and the closing of the concentration camps in 1907-1908 did not see the cessation of hostilities, as the slaughter of Herero, Nama, and others continued until South African forces took over South West Africa and replaced the German colonial state in 1915. Although there was an overt effort by the German State to cleanse the archival records of evidence of genocide and massive human rights violations, efforts were made by victim groups to keep the knowledge of the first genocide of the 20th century alive and to commemorate the losses of Herero, Nama, San, Damara, and others.

One of the bitter reminders of the genocide was the presence of human remains of Herero, Nama and San in German museums, medical schools, and hospitals. Skulls, bones, and whole bodies were experimented on by German scholars over the next century. Some of the experiments were aimed at attempting to justify the racist scientific theories which underpinned German physical anthropological perspectives on race until the end of the Second World War and beyond.

In some cases, Herero and Nama human remains were put on public display in museums. There was a general outcry in the early part of the 21st century when the treatment of Herero and Nama remains became public, especially when stories were told of Herero women in the concentration camps at Luderitz and Swakopmund being forced to prepare the skulls of people who died in the camps for transport to German institutions.

There were some small measures of success, however, with, for example, Germany’s decision at the beginning of the 21st century to repatriate Herero and Nama skulls and other human and cultural remains to Namibia. The repatriation of these remains took place between 2011 and 2018 from German hospitals, museums, and other institutions. There were no formal apologies, however, for the ways in which the Herero and Nama human remains were dealt with while they were in German hands.

Between 1904-1907, German military forces, called Schutztruppe, committed a genocide against indigenous people in their colony of German Southwest Africa (present-day Namibia; hereafter, GSWA). The intent of these killings—which occurred through battle; through starvation and thirst in the Omaheke Desert; and through forced labor, malnutrition, sexual violence, medical experiments and disease in concentration camps—was to rid the colony of people viewed as expendable and thus gain access to their land.

This genocide, the first of the twentieth century, was a prelude to the Holocaust in both the ideology of racial hierarchy that justified the genocide and in the methods employed. Such linkage between the two genocides has been termed the “continuity thesis.” Historians estimate that approximately 80,000 indigenous people were killed in the genocide. While these numbers are difficult to confirm, this figure represents about 80 percent of the Herero people and 50 percent of the Nama people.

Now, more than a hundred years after the genocide, the government of Namibia is seeking reparations from Germany for land stolen and lives lost. A significant portion of the most arable land in Namibia is still owned by descendants of the German settlers. Germany has not formally apologized for the genocide but is engaged in bilateral discussions as to when and if it will do so. To date, Germany has steadfastly refused to consider payment of reparations.

is it real ?

During the years in the late 19th century when Namibia was a German colony, the Germans alternately favored one tribe, the Herero, over another, the Nama. But when the territory’s resources were drained by the building of a railroad into the interior, the Germans essentially began confiscating all the land from both tribes. When the Herero rebelled, an “extermination order” was issued, and the remaining tribesmen were used as unpaid laborers.