The Mole and the Hyena

…the blue infinite straight line which must pass under what is below and over what is above… — Jacques Lacan, Seminar XXII

I am twenty-six years old and uninsured. A genetic condition has left me with severely bowed legs and pronated arches; my ankles, knees, hips, and lower back radiate pain. While staying with a friend during a move, I lift a box, my hip gives out, I collapse back onto the sofa. For twenty minutes I lie there, unable to stand. I am stuck in a hunched position for several days. With knees and hips that do not align and no arches to absorb the shock, the impact of walking goes straight to my spine: it feels like I propel myself on knuckles instead of feet. Bent before the mirror, I wonder if this is how people see me, wonder what value I hold in their view.

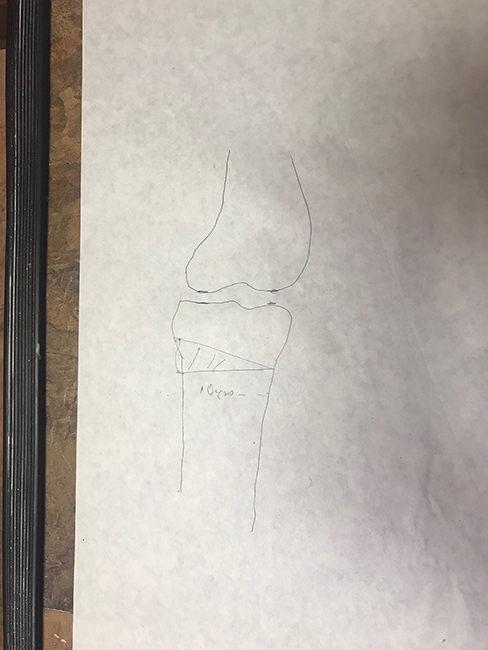

I don’t have a car. My grandparents pick me up from the Anaheim metro and drive us to Las Vegas. They take me to their orthopedist, who makes inserts for my shoes. While the inserts cool, the orthopedist draws two lines on the white paper beneath me. “That’s your knee,” he says, drawing another line that cuts across my figurative tibia. “They’ll probably take a pie-shaped slice out of your leg below your knee.” We leave after my grandfather pays for the $280 inserts, which, to be fair, earns us a second set at no charge. The doctor’s premonition, through far from welcome — I’m waiting for it to come true — is elucidating, refreshingly specific.

I ride with Chelsea to Fullerton, buy our lunch as thanks, then take a train to Irvine to see an exhibition at the university — Ella de Búrca’s Flat As The Tongue Lies. The show traffics in minimalism (think Robert Morris and Felix Gonzalez-Torres) while curator Allyson Unzicker’s catalog essay mentions figures like Barthes, Beckett, Cixous, and Lacan (and, more importantly: Billie Whitelaw). 1 I’m wearing my inserts, but it still hurts to walk. The bus route I planned doesn’t seem plausible. I call a Lyft and the driver takes the wrong exit, which leads to an extended detour. I begin to worry about money while I watch the driver spend mine each time he goes the wrong way. I should be writing and looking for work. But, I remind myself, I cannot write without research and I cannot research without travel and the only reason I can afford travel is my research into visual art.

The exhibition, though moving, cannot disappear the university campus or the golf course near the campus or any of the reflective buildings that shine among themselves in the distance. The R1 research institution conjures associations with the American military; all the works in the show have some electronic component (the risographs, too, come from a digital printer); I can feel the grid easing over the landscape. Unzicker and I talk about feminism, #MeToo, closet dramas, and Brett Kavanaugh, who is approved by the Senate Judiciary Committee hours later. She tells me the city of Irvine is a product of the Irvine Company, which owns most of the land in the area. I lament what I know to be true: there is always more context than the word count allows.

But there is also the context we suppress to uphold our perspectives. Context, like identity, is a way of seeing and being seen. There are facts, that, though true, compromise the truth they would otherwise indicate. I, for example, am often expected to mention that I am black or queer when advancing an argument that touches on race or gender, which in turn means I am often asked to write about race and gender. If I withhold my identity, my claims appear unjustified; if I disclose it, I speak a limited truth — no one challenges my argument according to what I say but rather that I, a person with a given set of identity markers, have even made an argument. How I sound and appear, how I am registered and categorized, often receives more treatment than what I have said. (This assertion extends to all the social spaces I occupy.) Or, as is often the case, I enter a room in which the artist is white, the curator is white, and the gallery attendant is a person of color. It becomes my task to negotiate, albeit privately, the parties and forums to whom this information may be imparted, to whom it must be muted or silenced. I respond to this condition by switching identities, perspectives, arguments, fidelities, institutions, performances, titles, and attitudes in accordance with the occasion. I want to be recognized for my particular attributes, my particular ways of thinking. It helps to start where one has gone wrong and proceed in an idiosyncratic manner. It’s not breaking the rules until the rules have broken you.

The publication where I plan to send the exhibition review pays a $100 honorarium, of which, if my pitch takes, I will have spent more than half by the time I purchase my return ticket. Aboard the train, a stranger who claims to work for the county flirts with me, says he grew up moving between the coasts (“bicoastal”), says he could help me find temporary work; I give him my phone number and a copy of the exhibition catalog. When we arrive, he walks me to the subway even though it’s in the opposite direction of where he’s going. He thinks I’m naive, but I’m playing dumb because I want to know what he thinks will come of our encounter. I’m a sucker for predatory types. The wedding ring, if he wears one, disappears from his hand.

In the weeks after seeing the exhibition, the orthotics I wear make me obsess over prostheses. It becomes difficult to separate anything, especially artworks, from their support mechanisms. At what point, I wonder, does Unzicker’s catalog stop being a catalog and become an extension of the show, if not the show itself? I don’t entertain this question very long because I’m more interested in whether the artworks or the catalog, the artist or the curator, serve as the prosthesis: Who — the artist, the artwork, the curator, the viewer, the critic, the public at large, the unwitting bystander — is upholding whom? These designations correlate to codependent identities, performances; identities and performances that vie for recognition, authenticity. Am I less black, perhaps queerer, when writing art criticism? No, I’m only black, de facto queer, when I write. I have to write in order to be anything. I have to perform if I want to be seen.

Today I am the mole. I enter the institution, burrow into its confines, exploit its use of space, peruse its archive. I issue a report from the field. But tomorrow I am the hyena, the female hyena. My genitals don’t correspond to the popular idea that splits the sexes into two. My labia form a scrotum and my clitoris is the length and width of a penis. Intercourse is difficult, painful but necessary. And I like it that way. I don’t want to continue unless there is pain. The pain makes tomorrow tangible, my survival tangible. I can’t live apart from the sensorium that hinders my progress because it is my lifeline, it is the sum of my movements.

I like Lacan’s suggestion that consciousness is where we are not; that the exhibition and the catalog are linked in ways I cannot fathom or represent without fictionalizing; that I am the fiction. The line drawing the doctor improvises to describe the surgery strikes me as a work of genius for this reason: it made my grandmother, sitting behind me, wince; it brought the impending future into view. In writing about the show, I resolve to become either the wince or the line but not the hand which subordinates them. After three failed drafts, I feel that am still the hand. I feel like writing criticism dirties my status as viewer. I cannot write with my own voice; I always become someone else. Or that someone else is me. I, too, am prosthesis. But no article means no return on investment. No return means no proof the performance sold. No performance means the prosthesis didn’t take. No prosthesis means no platform on which an identity may grab hold.

My feet brought me into psychoanalysis. I’ve been obsessed with cutting them off, with removing my deformity, since I ruined my first pair of Chuck Taylors in the sixth grade. I knew then that I was unlike all the other kids; it was my first editorial impulse. Deformed feet, bowed legs, black, a closeted queer: this was the preamble to my entry into analysis. No one wants to hear me discuss psychoanalysis; how psychoanalysis saved my life; how psychoanalysis made it clear that my desire to remove my feet was attached to my desire to remove my penis and testicles. I understand that no one cares about that. No, they want me to write about my identity and its comorbid suffering, its politics. I’m supposed to stan black and trans artists, because that’s what I am. But only certain black and trans people, and never at the expense of white women. No critical views of Maggie Nelson. No suggesting that what Chris Kraus and Kathy Acker have in common is their income as landlords. I think about all this after leaving David, my suitor, at the train. “So what are you?” he had asked me, and once again I am surprised that the ambiguity of the question never fails to proffer its meaning. At least David, unlike many an editor, has sincere curiosity when he asks.

Maybe I should come out and say it: A human being is the best pedestal a sculpture could ask for. A living support mechanism that keeps a painting aloft would at least demonstrate the gravity that pulls the painting to the earth. Gallery attendants would have to rotate shifts when tending the works. Passersby could see the kunstworkers shake, stretch, grow uncomfortable. It would require a greater effort to ignore the human quotient that makes the perception of artworks in spaces such as museums possible. We would have to understand the ridiculous conditions under which we ask these workers to perform just so we can venerate objects. If this weren’t already an ironic description of the labor gallery attendants, invigilators, visitor service associates, and other minimum-wage staff conduct in order to service elite institutions, I might even suggest that if someone dropped a painting the nearby viewer would experience empathy. Given these working conditions, which I have seen with my own eyes, there can be no critique of art or art institutions until the paintings have been dropped, recovered, and then searched for injury. (Who, in this case, has suffered: the laborer or the painting?)

It has been my job to walk in front of a crowd and convince them that I am black, that I am a black person who can talk about art. It has been my job to convince people that my knowledge is inferior to their own while parading them around an institution they lack language to describe. I have, willingly and unwillingly, been a crutch that has supported this system. I have made a living selling my face to other people. I have profited from the exchange of human collateral. I have gambled with the lives of my friends and peers. Because that is what it means to operate within the institutional sphere. I recommend those without a spirited sense of optimism hedge their bets. The face, if it is returned, does not come back the same as when you lent it.

What really interests me is dissection. Removing the parts to understand which are faulty. But who determines what is and isn’t faulty? I’ve taken Flat As The Tongue Lies apart several times and notice I end with more components and start with fewer each time. (This is a measure of its success.) Unzicker’s Lacan references lead me to my bootleg copy of Seminar XXII, then Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, then, at a friend’s suggestion, Friedrich Kittler, whom I had never read. But that is the damage art writing has done to me. The search for the proper context and objective tone, the neutral aptitude, the prosthesis which acts like a salve and wipes away what is somehow missing even when it’s there, so visibly there I can feel it holding me up. They’re going to shorten my goddamn legs, I think, and it feels like an apt description for what art criticism, if it means to set a body upright, must do.

If all identities are prosthetic, what happens when the smidgen of support they provide is taken away? Smidgen, of course, being a relative term. I can’t walk without mine. I’ve never been to the continent — Africa — whose name my appellation carries. Like I said, my opinions are deformed. To paraphrase the doctor: No matter how I proceed I’ll spend the rest of my life tarrying with pain, swelling, discomfort. My cartilage will age and degenerate. There isn’t much I can gain but even the things I don’t have I can lose.

- I had never heard of Whitelaw until reading about her in Unzicker’s catalog. A quick scan of her Wikipedia page reveals she had a significant role in Beckett’s theatrical output and held roles in films such as Frenzy (1972), The Omen (1976), The Dark Crystal (1982), and Hot Fuzz (2007). Beckett was arguably dependent on Whitelaw as a collaborator. While Wikipedia uses the term “muse,” I prefer to offer her as an example of the prostheses I describe; she illuminates the gender politics afoot in citation practices, revealing them as ideological prosthetics. Beckett aficionados who have not once considered the actors who put on his plays but can reference critical text after critical text where Whitelaw goes unmentioned come to mind. Myself included.

Comments (4)

Aaw, but life is fresher and sweeter then tasted, a common ground, where misunderstanding meets, contemplation. The treasure hunt, but yet, the journey yet to b travelled. I am, intrigued to read more about the authors u have referred to, by the same collision of research. Very well written lover, please continue to illuminate, but only if it’s from u. Thanks Ev

Stunning and cutting piece on the hidden labor and personal costs of art writing and working in the art world. Beautiful.

Deformed thinking as a theme, I can relate to my own thoughts. Enjoyed the piece, keep it up.

The only opinion I have of this works is that this is my grandson in who I am extremely extremely proud good grief you’re a great writer.