Jamie Holley’s Plastic Dreams

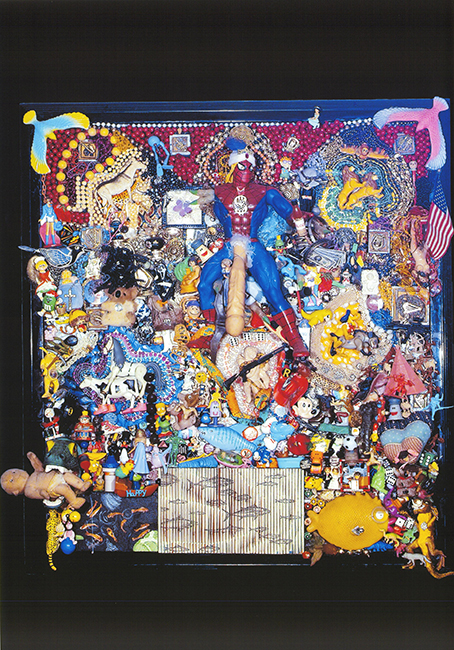

Jamie Holley, Untitled, 2006–2009; mixed-media assemblage.

Diana Vreeland could’ve been describing Jamie Holley’s assemblages when she quipped, “I’m a great believer in vulgarity — if it’s got vitality.” Undeniably garish and teeming with life, Holley’s pieces are, simply put, too much. Plastic action figurines, small stuffed animals, novelty key chains, Mardi Gras beads, yesteryear’s Happy Meal prizes, and tacky phallic party favors spill across whatever surface they’re glued to like the ersatz contents of an overturned toy chest. Each item, a casualty of passing interest until Holley plucked it from the depths of a dumpster or a yard sale’s bargain bin, gets a second chance to clamor for our attention. The visual noise can be deafening; Holley’s pieces repel apprehension in the aggregate as they bum-rush your vision with so. much. stuff.

Isn’t it kitsch? As if anticipating the charge, Holley half-jokingly called these pieces — made in a whirl of activity between 2006 and 2009, the year he died — his “white trash series.” The question — a Greenbergian gag reflex — is a boring one in any case, and not helpful in describing the affective charms of so much organized chaos. Bruce Boone, who was Holley’s partner for nearly two decades, offers an alternative take in the online mourning diary he kept after Holley’s passing. Running with Holley’s assessment, he lovingly characterizes the assemblages as “ditzy.” Ditzy. The word fizzes on the tongue like soda (“champagne” feels too posh; Holley strikes me as more Goldie Hawn than Marilyn Monroe). Boone writes:

His art was outsider art I guess because he had no art-school training but also because there was an unwitting gullibility to it. […] His gullibility was the opposite of calculating, was foolish — if you take getting-ahead as your standard.

Vulnerability can also oppose calculation, just as guilelessness can be gullibility’s silver lining. I think about how physically fragile Holley’s pieces are, despite their seemingly impenetrable carapaces. I recall removing one from above Boone’s bedroom doorway with the help of my partner; it was going to be part of an exhibition I organized featuring art from the personal collections of Boone, Bob Glück, Jocelyn Saidenberg, Kevin Killian, and Dodie Bellamy, all writers who have become associated with New Narrative. Gently loosening the haphazardly installed L-hooks that stabilized the piece — the clusters at its outer edges framing a beneficent sun — we lowered it from its spot covering the transom. The backing was revealed to be a white board advertising a yard sale, its middle now sagging slightly under the weight of its heavily encrusted front. Descending our respective ladders, step by step, I felt as if we were Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus gently lowering Christ’s body from the cross.

Though his art was largely unplanned, and depended on whatever materials were on hand, Holley’s serried surfaces reveal an internal compositional logic that pulses with visual interest and activity. Some assemblages foreground their geometry, the arrangement of elements recalling the tracery of a rose window. In others, the drama is proximal, as in the vignettes, mini-narratives, and ribald sight gags that emerge when one zooms in on a particular quadrant or figure. The assemblages also, somewhat perversely, recall the bright colors and concentric arrangements of Tibetan sand paintings, those temporary accretions meant to underscore the concept of impermanence. The mass-produced components of Holley’s compositions are far from transient, though — most types of plastic take four hundred to a thousand years to decompose. As delicate as Holley’s artificial pleasure gardens are, it’s hard not to think that the flowers they contain will remain long after our gazes have ceased.

All works: Jamie Holley, Untitled, 2006–2009; mixed-media assemblage.

Comments (1)

What a delightful group of works to view! GRACIAS!

I’m not familiar with his work…would like to view more…but, where?