Plenty of Skin

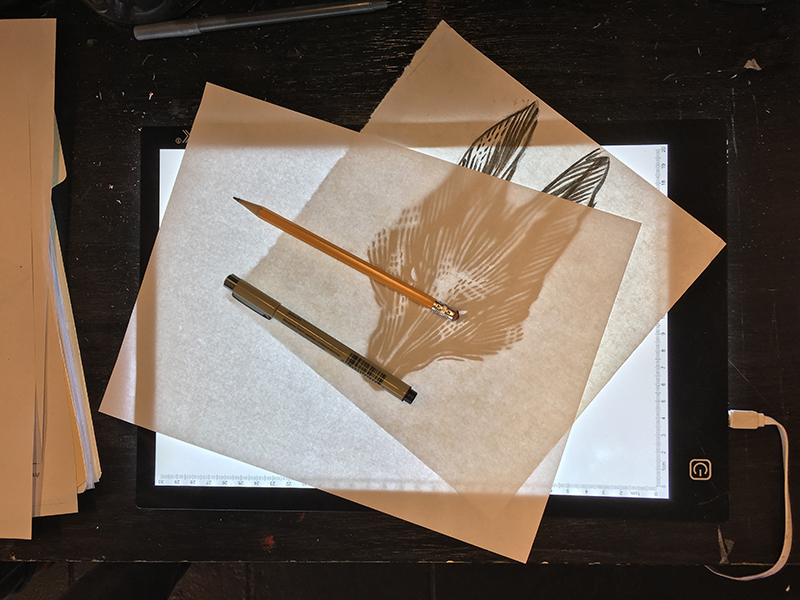

All photos by Dustin Mabry, 2018.

Guy Prandstatter said it’s just a “realization” of a “better fucking way of doing things.” Co-founder of a tattoo school network, he described a growth in tattoo schools as following the industry’s popularization and professionalization. “Nothing first came into the world as a formal school.” He asserts schools will replace the tradition of apprenticeship-training just as “medical schools replaced whatever came before them.”

And I couldn’t even finish saying “tattoo school” without Oakland artist Freddy Corbin protesting, “That’s a complete bastardization!” I was met with a resounding “Booooo!” upon using the words in another shop, and elsewhere encountered a nearly ubiquitous echo of one artist’s succinct statement: “Seriously. Fuck those guys.”

Meanwhile, a queer artist who requested anonymity suggested schools may offer a more inclusive way into tattooing, if they didn’t charge too much and “actually taught people to tattoo.” They otherwise championed the efficacy of self-training, and of created new models for apprenticeship.

These responses highlight a cultural struggle in tattooing in the US. Traditionally, newcomers arrange one-to-three year apprenticeships with established artists. Typically unpaid, apprentices answer phones, arrange equipment, and begin tattooing after varied time learning shop organization. 1 Artists who don’t apprentice are often labeled “scratchers” and rejected from shops and conventions. 2 With varying degrees of nuance, school supporters view apprenticeships as antiquated protectors of macho culture, while critics present schools as predatory scratcher-promoters. Underlying this schism is a disagreement over who has the power to distinguish good artists from bad.

In 2010, Prandstatter co-organized the Academy of Responsible Tattooing (ART) in New York to “revolutionize the tattoo industry” by training those outside the “renegade or law-breaking stereotype.” It seems this revolution is not itself entirely standardized; after students attend a $379 workshop they enroll in a yearlong program, the costs of which multiple sources declined to reveal. I was told by one that the amount is “not straightforward.”

During an interview, Prandstatter suggested critics conflate “tattoo schools” with “short-term bullshit” while describing his schools as emulating the valuable aspects of apprenticeships. The difference, he claims, is “an actual contract” and that you avoid being “fucking hazed.” According to him, of the roughly ninety people who have graduated from his program, fifty-five tattoo in one of ART’s shops, thirty “went to existing tattoo culture,” and the remaining individuals left the field. He noted that, to avoid association, graduates don’t mention their school training in their professional portfolios, adding, “I’m okay with that, I understand it.”

Prandstatter didn’t dispute the efficacy of the apprenticeship ideal but challenged me about the reality: “Show me one of these great apprenticeships.” He suggested people join schools after being rejected from “macho” cultural barriers, something substantiated by Rhonda, a school graduate currently working in one of ART’s shops. She eschewed traditional apprenticeship for the school, which she called a “wonderful experience” where she felt “accepted” and able to tattoo “rather than mop floors.”

Acknowledging that apprenticeships are imperfect, Oey from Sacred Tattoo nonetheless echoed Prandstatter’s ideal/reality distinction from the opposite position, saying schools sound good but actually “sell pieces of paper.” Dan Gilsdorf of Atlas agreed, arguing schools foreground “ability to pay” over “merit and dedication.” 3

I spoke with several queer artists (who, tellingly, all requested anonymity) about apprenticeships. One called usual apprenticeships “white dude privilege at its finest,” suggesting them as sites for sexual and racial harassment. Another added, “Designs from women [are] called ‘too delicate’ [then] stolen by dude artists.”

Women, queer folks, and people of color have responded 4 to what they describe as systematic biases by establishing shops, 5 organizations, and festivals. The Queer Tattoo Alliance, for instance, presents itself as a “response to the exploitation” while Modern Electric Studio of Oakland calls itself an “explicitly feminist” shop. Sezin Koehler, a writer and critic, focuses our attention on colorism in tattooing by explaining the tendency of tattoo artists to prefer light skin — an “irony” of “skin-shaming” as “tattoos were invented by brown and Black people.”

Yet many I spoke with who shared such nuanced insights as these suggested schools won’t solve deeply systemic problems in the tattoo industry. Instead, they supported the development of feminist shops, of respectful consideration in diversified modes of training, and of less-exploitative apprenticeships.

One individual I spoke with described the struggle unfolding in a “culture of ownership.” And this may be the crux of it: In the face of limited resources, the tensions around tattoo schools reflect a broader conflict over who and what has the power to serve as gatekeeper. It arises in a moment when the degree to which established artists determine who is “in” or “out,” through control over apprenticeships, is challenged.

There are reasons to suggest the apprentice-or-nothing stance may wane over time. It’s reasonable to think that, over time, school-trained artists will cease to feel a stigma and actively promote school-based training to their mentees. As well, the rise of viable alternatives, such as feminist tattoo shops, may leave tradition-pushers sounding increasingly conservative, and therefore ignored by up-and-coming artists.

Or maybe this isn’t the case at all. Perhaps the struggle tests the degree to which tattooing can handle multiplicity. “Your turn’s over, BROS!,” one artist proclaimed. But what if there’s plenty room for traditional, certificate-holding, and self-taught artists? What if there is, as one artist put it, “Plenty of skin?”

- The actual time spent in a shop before tattooing varies greatly. I was told that a person can start within a few months or after as long as two years.

- DeMello, Margo 2000. Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. (See pgs. 52, 94 on apprenticeships and pg. 5 on scratchers.)

- See this organizing effort against schools for more: http://www.notattooschool.com/about/

- See Mifflin, Margot 2013. Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. Brooklyn, NY: Powerhouse Press.

- See Black and Blue, Castro Tattoo, Bulldog Tattoo, Modern Electric Studio, and Diving Swallow Tattoo in the Bay Area.

Comments (3)

Reading this I was struck by similarities I experienced in the world of photography. Technique can be taught and creativity can be developed in schools, but a lot of knowledge and experience can best be learned while working for someone else. The days of formal apprenticeships in photography are long gone, replaced by schools and programs, but there are still many photographers out there who are self taught and learn as they go through books, workshops and internships. What seems to be consistent between these different fields is the establishment’s resistance to change and the defensiveness of long time artists protecting their turf by shooting down the new class of artists coming into the field.

Nothing is ever what it seems at face value. An abundant multilayered look into current tattoo culture, what it is like, and what it may be.

Interesting perspective on a subject I had little knowledge of.