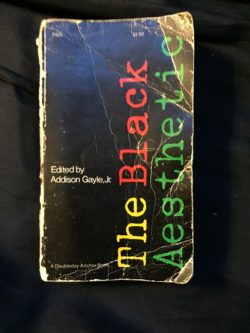

The Black Aesthetic (Anchor Books, 1972)

Afro-Surreal presupposes that beyond this visible world, there is an invisible world striving to manifest, and it is our job to uncover it.

I began rummaging through my parent’s extensive collection of Black Radical text and ephemera when I was fourteen years old. From a series of metal shelves in the basement, next to the washer and dryer, I pulled Martin Luther King Jr.’s Why We Can’t Wait, Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and from which my mother gifted me my first copy of Ishmael Reed’s book of poems, Chattanooga, introducing me to the writer who would later become my friend and mentor. It was during one of my many excavations through posters of Malcolm, postcards of Fred Hampton, and lapel pins saying “Free Huey!” and “Free Angela!” that I first ran across Addison Gayle Jr.’s The Black Aesthetic. It was love at first sight.

I loved the fact that it was a pocketbook (not rare back then, but definitely practical for a kid to shove in his back pocket). I loved the Courier font running down the side in yellow, red, and green, completing The Colors with a black background. It looked like the most serious book in the world to me.

The table of contents didn’t disappoint either. Alain Locke with an excerpt from The New Negro, W.E.B. Dubois, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes and, lo and behold, Ishmael Reed! At the time, these were the only names I knew, and I learned of writers like Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, Sarah Webster Fabio, and Keorapetse Kgositsile (father to hip hop artist Earl Sweatshirt) through my initial encounters with this book.

The Black Aesthetic and I have been together for over thirty years. It traveled with me through several states and in several different iterations. Moving from milk crate, to book boxes, to various shelves in multiple apartments, through relationships, and through the never-ending struggle of a Black man writing in America. Alain Locke’s “Negro Youth Speaks,” from The New Negro (1925) guided me:

Our poets have stopped speaking for the Negro — they speak as Negroes. Where formerly they spoke to others and tried to interpret, they now speak to their own and try to express. They have stopped posing, being nearer the attainment of poise.

Inspired by Locke, Langston Hughes’ “The Negro Artist And The Racial Mountain” (1926), motivated me:

We younger Negro artists who create intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

The essay “Tripping On Black Writing,” by Oakland’s own Sarah Webster Fabio, sustained me with both inspiration and examples:

Alain Locke — that necessary critic for The New Negro: a special critic for a special time. Harlem Renaissance. Fathering Negritude. Giving possibility of showing forth a triumph of spirit and mind. A decolonized mind shining through colonial language.

Zora Neale Hurston, anthropologist, throwing light on language. Open the way for today’s freedom-wigged freaks. Stone-cold, bad blood revolutionaries. Escapees from the prison of Anglo rhetoric. Frontiersmen in the lumbering Netherlands of Black language. Medicine men schooled in witchcraft, black magic, the voodoo of words. Immortalized, subterranean, out-of-this-world travelers.

Black Writing — repressed, suppressed, ignored, denounced. Black writers having rained upon them not respect, riches, rewards, but disrespect, discouragement, non-recognition, deculturation, derangement, assimilation, isolation, starvation, expatriation, criminal indictment. LeRoi Jones’s case but a recent and flagrant example of a system’s way of dealing with creative, liberated black minds.

Placing that last quote next to James A. Emanuel’s “Blackness Can: A Quest For Aesthetics”:

When black authors are allowed to profit from the black vogue, trade publishers either use more highly-selective criteria in granting contracts or otherwise alter their standards — the end result being invariably the exclusion of too many able black authors and critics. Sometime these trade publishers, turning semi-political, enforce the exclusions through the sinister practice of blacklisting.

It’s a wonder that I wanted to be a writer at all! But I did and do. Thanks in no small part to books like my old, dear, constant companion The Black Aesthetic.

My plan was to review this book and make a serious call to you, good readers, to help me appeal to Anchor/Doubleday for a reissue of an important single-print anthology that had been buried in time. But first, I had to read it in its entirety. Something, I realized, that I’d never done.

In certain kinds of relationships, we have a tendency of seeing only the best in a person, ignoring minor quirks, and even warning signs, in order to maintain our perception of them, especially when it was love at first sight, and we’ve been together for so long. This was my case with The Black Aesthetic. All the red flags had been there all along. I just chose not to notice them. But scrutiny always messes up that gambit. Roland Barthes calls it “the tip of the nose,” in A Lover’s Discourse:

I perceive suddenly a speck of corruption. This speck is a tiny one: a gesture, a word, an object, a garment, something unexpected which appears (which dawns) from a region I had never even suspected, and suddenly attaches the loved object to a commonplace world.

It begins in Gayle’s Introduction, where he writes:

Each has his own idea of the Black Aesthetic, or the function of the black artist in the American society and of the necessity for new and different critical approaches to the artistic endeavors of black artist. Few, I believe, would argue with my assertion that the black artist, due to his historical position in America at the present time, is engaged in a war with this nation that will determine the future of black art.

Upon closer inspection that “war” was placed in a curious context. America, as a nation, has been at war with Black people since before slavery. How then, could a ceaseless centuries-long war in America determine a new future for black art? Unless, of course, he was not referring to America, but a new nation in the midst of a new war.

The Black Aesthetic Movement this anthology was created to initiate, began as a series of debates in The Negro Digest in 1968, but was exemplified by Hoyt F. Fuller’s “Towards A Black Aesthetic” for The Critic that year:

The black writer, like the black artist generally, has wasted much time and talent denying a propensity every rule of human dignity demands that he possess, seeking identity that can only do violence his sense of self. Black Americans are, for all practical purposes, colonized in their native land, and it can be argued that those who would submit to subjugation deserve to be enslaved.

This (I now see) abusive paragraph would later be the opening for Don L. Lee (Haki Madhubuti)’s Dynamite Voices: Black Poets Of The 1970s, along with one from Gayle, in the Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) edited African Congress: A Documentary of the First Modern Pan-African Congress, which also came out in 1972.

Further, he claims the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) are, “The young writers of the black ghetto [that] have set out in search of a black aesthetic, a system isolating and evaluating the artistic works of black people which reflect the special character and imperatives of black experience […] Aiming towards the publication of an anthology which will manifest this aesthetic, they have established criteria by which they measure their own work and eliminate from consideration those poems, short stories, plays, essays and sketches which do not adequately reflect the black experience.”

OBAC, which later became AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artist), which was created, (according to a recent article in TATE ETC. Magazine) “to reflect the pan-Africanism sweeping the country that envisioned black liberation as a global struggle […] continued to call for a people’s art by producing positive images of black leaders and everyday people,” was, in fact, an organization that Fuller himself founded and sponsored, though you would never know this from his description. What’s telling in that paragraph is that we see the question is not “Is there a black aesthetic?” or “What is the black aesthetic?” So much as, “Who controls and determines the black aesthetic?” This is the thread that strings the book together.

Maulana Karenga — founder of United Slaves, inventor of Kwanzaa, and possible FBI agent — writes in Black Cultural Nationalism:

…all art must reflect and support Black Revolution, and any art that does not discuss and contribute to the revolution is invalid, no matter how many lines and spaces are produced in proportion and symmetry and no matter how many sounds are boxed in or blown out and called music.

We say individualism is a luxury we cannot afford, moreover, individualism is, in effect, non-existent. For since no one has any more than the context which he owes his existence, he has no individuality, only personality. Individuality by definition is ‘me’ in spite of everyone […] We say there is no virtue in false independence.

Tradition teaches us, Leopold Senghor tells us, that all African art has at least three basic characteristics: that is, it is functional, collective and committing or committed. Since this is traditionally valid, it stands to reason that we should attempt to use it as a foundation for a rational construction to meet present day needs. And by no mere coincidence that we find the criteria is not only valid, but inspiring […] Art will revive us, inspire us, give us enough courage to face another disappointing day. It must not teach us resignation. For all our art must contribute to revolutionary change and if it does not, it is invalid.

Therefore, we say the blues are invalid; for they teach resignation, in a word acceptance of reality — and we have come to change reality.

Amiri Baraka contradicts Karenga in “The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)”:

The ‘new’ musicians are self-conscious. Just as the boppers were. Extremely conscious of self. They are more conscious of total self (or want to be) than R&B people, who, for the most part are about self-expression. Many times self-consciousness turns out to be just what is as a common figure of speech. It produces world-weariness, cynicism, corniness. Even in the name of Art. Or what have you… social uplift.

In “Black Arts: Notebook,” John O’Neal accuses Langston Hughes of being in “The Coon Trap” saying, “Langston Hughes (tch-tch-tch)” — I, Too (published in numerous collections).

Poem For A Knee-grow

(I don’t care to meet)

He was born here

His forefathers died here

Fought here

Worked here

Their graves are here

In a marri ca

But are you really, bother

Chickens are born

In an oven sometimes but that don’t make um

Biscuits, nigger

Asood Akibas, Nkombo, fall 1969”

Hughes had been dead for five years. His contribution, like Richard Wright’s, was posthumous.

In “You Touch My Black Aesthetic And I’ll Touch Yours,” Julian Mayfield claps back at some as-yet-named-and-placed literary fuckery:

Those who dare to attempt the act of creation must not be put off by the difficulty in finding an exact definition for the Black Aesthetic. We must not be distracted by that bewildering combination of forces the poet Margaret Walker described more than thirty years ago in her poem For My People:

…Distressed and disturbed, and deceived and

Devoured by money-hungry, glory-craving leeches,

Preyed on by facile force of state and fad and

Novelty, by false prophet and holy believer…

For those who must create, there is a Black Aesthetic which cannot be stolen from us, and it rests on something much more substantial than hip talk, African dress, natural hair, and endless, fruitless discussions of ‘soul.’ It is our racial memory and the unshakable knowledge of who we are, where we have been, and, springing from this, where we are going.

In “The Black Aesthetic In the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties,” Dudley Randall does him one better by quoting the aforementioned Hughes quote, writing:

This sounds like the Black Aesthetic credo, but there are significant points of difference. For instance, Hughes uses the word Negro. Negro ideologues have forbidden Negroes to call Negroes Negroes. Hughes stresses individualism (‘express our individual dark-skinned selves’). In the Black Aesthetic, individualism is frowned upon. Feedback from black people, or the mandates of self-appointed literary commissars, is supposed to guide the poet. But Hughes says, ‘If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not their displeasure doesn’t matter either.’ (Another expression of individualism.) Hughes says, ‘We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.’ In the Black Aesthetic, Negroes are always beautiful.

In my own opinion, this feedback usually comes from the most vocal group, ideologues and politicians, who are eager to use the persuasiveness of literature to seize or consolidate the power for themselves.

GODDAMN!

Larry Neal in The Black Arts Movement claimed:

The Black Arts Movement represents the flowering of a cultural nationalism that has been suppressed since the 1920s. I mean the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ — which was essentially a failure.

Later, when both he and Gayle take covert digs at Ralph Ellison, I realized that those are the only two times his name comes up. It made me wonder what other name or names were being blacklisted, or as Fabio described, subject to “disrespect, discouragement, non-recognition, deculturation, derangement”? What was the urgency that triggered this quest for the black aesthetic in the first place?

Ishmael Reed’s contribution to the anthology is disappointing. I was disappointed then, and I’m still disappointed now. Not so much because it is poorly written or executed, but because it’s from the introduction to his anthology 19 Necromancers From Now that came out with Anchor Doubleday in 1970 and I’d read it already. It was like he “phoned it in” or was too busy to care. But considering how prolific the young Reed had been, besides fellow Oakland resident, Sarah Webster Fabio, his name isn’t mentioned at all either.

Ishmael Reed’s first novel, Freelance Pallbearers, came out in 1967. The original review of the book in Newsweek read: “For all the talk of the black aesthetic, few black novelists have broken sharply with the traditional devices of the realistic novel. One writer who departs from such conventions, however, is Ishmael Reed […] The Freelance Pallbearers uses an explosive combination of straightforward English prose, exaggerated black dialect, hip jargon, advertising slogans and long, howling uppercase screams.”

In 1969 Reed published Yellow-Back Radio Broke Down, which the New York Review Of Books called, “a full blown ‘horse opera,’ a surrealistic spoof of the Western with Indian chiefs aboard helicopters, stagecoaches and closed circuit TVs, cavalry charges of taxis.”

But it’s in 1972, the same year of the publication of Gayle’s Black Aesthetic and Baraka’s African Congress: A Documentary of the First Modern Pan-African Congress, that Reed launches his independent journal, The Yardbird Reader, Volume One. It’s 1972 when he publishes Mumbo Jumbo, a novel literary critic Harold Bloom calls one of the “500 most important books in the Western canon.” And perhaps most important of all, 1972, Reed publishes a book of poems, Conjure (which contains The Neo-Hoodoo Manifesto), and gets nominated for a Pulitzer Prize.

By looking at the corresponding dates (1967, Freelance Pallbearers = 1968, The Black Aesthetic Debate. 1972, Neo-Hoodoo Manifesto = The Black Aesthetic Movement), it’s clear that there were organized forces meant to “bury” Ishmael Reed or diminish his influence in false equivalence, due in no small part for his championing of what would later be called “multiculturalism,” which he had just introduced in The Yardbird Reader, Volume One.

Contrary to popular myth, Ishmael Reed was never a member of The Black Arts Movement. He was a member of a proceeding group, Umbra, along with Henry Dumas and others. And though it was attempted, The Black Arts Movement did not become interchangeable with The Black Aesthetic Movement, as Neal notes in the book. So, who were these organized forces? Were they governmental? Societal? Commercial? All in it together? I can scarcely imagine what Reed was thinking as all this fuckery was going on, but I have a clue.

Just as Robin D.G. Kelly said one could not critique Senghor’s “love of an African past,” without first taking into consideration that that critique could only happen in a postcolonial discourse, so, too, The Black Aesthetic cannot be critiqued without the rise of multiculturalism.

In Left Politics and the Literary Profession (Columbia, 1990), Pancho Savery’s text, the “The Third Plane at the Change of the Century: The Shape of African-American Literature To Come,” states: “Neal’s revision of his views on Ellison and The Black Aesthetic Movement is a significant moment in African-American literary history. It got him out of what Ishmael Reed and Stanley Crouch call ‘the opiate of ideology’ when ‘the romance [of black nationalism] began to fade in face of the megalomania, the lies, the avarice and interwoven monstrosities of totalitarian and opportunistic impulses’.” (Ishmael Reed, “Larry Neal: A Remembrance,” Callaloo, 1985).

Damn Ish!!!

I look at my former companion now with a cold dispassion. What I believed to be a love story to stand the test of time turned into a detective melodrama rife with deception, intrigue, and just-plain-ol’-fuckery, which is still too-common ‘round here these days.

Comments (1)

“The Black Aesthetic” by Addison Gayle Jr. is a significant book that explores the complexities and richness of Black culture and art. Its examination of the Black experience, particularly in the context of art and literature, provides a valuable perspective on the contributions and struggles of Black artists throughout history. By delving into the various themes and artistic movements, the book sheds light on the diverse expressions of Black creativity and challenges conventional notions of aesthetics. It serves as a reminder of the importance of representation and the power of art in shaping social and cultural narratives.