Nuns, Witches, and Teachers (Part 1: Family Values)

I grew up convinced that my school was located at one of the far edges of Bogotá. Back then, there were two perpendicular roads that ended right in front of the school’s entrance, one came from the South and the other from the East. In the rear of the school’s campus was a long bare brick wall. It began in the kindergarten area, passed through the elementary school section, and ended in the high school premises on the opposite side. This was the only structure that separated us from the thick green forest that covered the vast surrounding area with native flora and fauna and with the cold early morning fog, typical of the highlands of the Andes. This brick line was the physical boundary that separated our seemingly small and safe place from the infinitely unknown and dangerous reality of the world outside. Throughout the school campus, there were several single-story classroom buildings of varying shapes and sizes, surrounded by ample open areas designated for recreation and sport. The elementary and high school girls shared the majority of the basketball and volleyball courts, as well as the vast and well-kept green areas. The kindergarten girls had a separate recreational zone with playgrounds, a garden, and a small amphitheater. The administrative offices, the church, the cafeteria, the kitchen, the storage rooms, the workshops, the maintenance facilities, and the tiny hidden smoking room — basically all the spaces that could allow for the presence of adult outsiders — were all located around or close to the main parking lot, which was the first area one would find right after passing the guarded entrance.

I was probably eight or nine when I heard the rumor about the Marxists nuns. As was the case for most of my childhood, I remember more vividly the events and experiences that were somehow out of the ordinary or that were at the edge of or beyond anything I had been taught or had conceived on my own. Similar to the process of learning a language, I tended to invent meanings and visual images for anything I didn’t understand or couldn’t place in a clear category, as it related to the context in which I had encountered it.

One day, while running around and playing on one of the volleyball courts, one of us noticed a hard shiny surface under the worn out grass of the court. We all immediately stared at it with fascination and started ripping up the knots of grass that were covering the mysterious treasure. It looks like a stone coffin… Maybe someone is buried here! Maybe this whole school was a cemetery before… Keep digging! Wait, look, there are tiles. Tiles? Yes, it looks like a floor… A floor outdoors in the middle of a potrero? It looks old…I bet it’s from the time when the nuns were running the school. Nuns? What nuns? The Marxists nuns that ran away! Don’t you know about them? Not really… The nuns created the school, they were also the teachers of the school… Can you imagine having nuns for teachers? Ugh, no! What happened to them? I’m telling you, they were Marxists and ended up fleeing… Or what if they didn’t run away and they’re all buried under these tiles?!

I was able to come up with a mental image for the word nun right away: an old inquisitive-looking woman wearing a long black dress, a white bib, and with a firm black cloth attached to her head, perhaps with the intention of simulating the presence of straight dark hair; a trick I also used when playing dress-up games back then. But Marxist was a word I almost certainly had never heard before. Even though my education was starting to be shaped by a series of binary concepts — good versus bad, selfish versus generous, feminine versus masculine, obedient versus rebellious — the fact that these nuns had to run away was beyond anything I could identify as either this or that. Maybe they were not real nuns but were women using a nun’s costume and unquestionable authority as a way to scare and enchant others, just like witches do? No, that didn’t seem likely. Regardless, I knew that these nuns were associated with some kind of trouble. What type of trouble, I couldn’t explain or invent an image for. My conclusion was that they either did something really bad or that someone wanted to do something really bad to them. Both options were possible, especially during the troubled Colombia of the 1980s I was indirectly exposed to.

I never asked my parents or anyone else for an explanation; I probably thought I was not supposed to know about them and could get in trouble if I brought them up. During the thirteen years I spent in that school, any association the institution could have had with Marxism seemed absurd and never came up. All I heard about the school’s founding was that its name, Fundación Nuevo Marymount, referred to the new and updated version of an old school that had been forced to close. So in the end, the story of the Marxist nuns remained as a fantastical memory invented during a childhood game.

Thirty years later, that particular memory, along with many other memories, impressions, and assumptions that shaped my early years, were challenged and reconfigured when I learned about Leonor Esguerra Rojas. Leonor, an articulate, confident, warm and serene eighty-seven-year-old woman, calls herself a feminist and activist today. As a fighter in search for social justice, she believes that the central battle facing the world today is the one against patriarchy. Después de mucho andar y buscar, llegué al reconocimiento de ser mujer dentro de la visión feminista que comparto con muchas otras mujeres. Esta visión que me ha permitido reevaluar viejos dogmas desde una esencia existencial más íntegra y proyectarme a nuevas necesidades de lucha por otras justicias ignoradas culturalmente a través de la historia. 1

Born in Bogotá in 1930, two years after the historical Masacre de las Bananeras that Gabriel García Márquez introduced to the world in his book Cien Años de Soledad, Leonor, or Ñoñó, as people knew her during the first chapter of her life, grew up within the comfort, assurances, and aspirations of a typical petit bourgeois family in the North of Bogotá. As a schoolgirl in the 1940s, she learned to understand that getting married and starting a family was all that young women her age were meant to aspire to and pursue. She had already passed through three international schools run by rigid and old fashioned nuns (which led her to hate nuns and everything they represented) by the time she arrived to a new bilingual American boarding school called Marymount, where she was positively surprised and influenced by the open, joyful, and fraternal spirit of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Mary who founded the school. In 1948, at the age of seventeen and aware that she had only a few months left before graduating from high school, Leonor knew that she didn’t want to get married, become a docile wife, and continue pursuing the trivial lifestyle other women in her immediate social context were so excited to have and be immersed in. What a frivolous life that was! Living from party to party, outing to outing? Marrying one of those mama’s boys? Being a housewife? Playing canasta? Well, no. 2 The only alternative for leaving the family home after graduating from school was to join a convent and become a nun, just like the friendly and open-minded American nuns who ran her school.

Even though Leonor was not particularly interested in social justice at that time and considered the presence of poverty in her immediate surroundings como parte del paisaje, como los árboles y las montañas, 1948 was a decisive year in the history of Colombia, with events that continue to shape its social fabric up to the present day. The assassination of the popular left-wing candidate of Partido Liberal, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, whose ideology represented a threat to the country’s powerful oligarchy and its exploitative interests, triggered the Bogotazo, a dramatic popular revolt, and the founding of new subversive groups, which ultimately led to the fifty years of civil war that just now seems to be reaching another stage, hopefully one of reconciliation, reparations, and peace.

After spending a year and a half in the convent of Tarrytown, in upstate New York, Leonor became a novice, adopted the name Mother María del Consuelo, and was sent back to the Marymount school in Bogotá, this time as a teacher. The first thirteen years or so of her life as a young nun and teacher in Bogotá and Barranquilla and, ultimately, as a Mother Superior and the Director of the Marymount school in Medellín, provided her with the tools and the conditions to put in place a series of progressive changes within the schools, most of which were welcomed with enthusiasm by her immediate community of nuns, students, and parents. On a few occasions, her liberal bent and assertive personality caused her some trouble. One day in 1963, without any explanations and without much notice, Mother María del Consuelo was informed that she had been removed from her directorship role at Marymount in Medellín and was expected in the convent of Tarrytown, where she was to spend a full year. Apparently, the answer she had given to a group of mothers who were demanding the removal of the daughter of a woman who had gotten divorced and remarried in a civil ceremony, had not been very well-received: If your daughters cannot study in the same school with this girl, then maybe it’s better if you look for another school for your daughters. 3

The United States that Mother María del Consuelo found was in the midst of a period of extraordinary transformation. President John F. Kennedy was murdered soon after she arrived, and the various activist movements were demanding that the nation address deep problems with civil rights, poverty, and a meaningless war in Vietnam.

Around this time, Pope John XXIII created the revolutionary Second Vatican Council (1962-65), which sought to renovate a Catholic church that he thought had become too separate from issues relevant to modern life, especially with its passive role during recent and present periods of war. A few years earlier, the pope had published “Mater et Magistra,” an encyclical on the topic of Christianity and Social Progress. It shook up many sleepy convents and monasteries with its promotion, among other things, of labor rights and equality, and its harsh questioning of the colonial and discriminatory ways Catholics had behaved with people who were different from them, including communists. Mother María del Consuelo’s discussions with her fellow religious sisters soon revolved around finding potential ways to put these teachings and ideas into practice.

When Mother María del Consuelo returned to Colombia in 1964, she was committed to following the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, as well as the advancements and ideas of the American Civil Rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr., the Young Lords in Puerto Rico, the Black Panthers, and Angela Davis. She soon became convinced that the Marymount Schools in Colombia, and elsewhere in the world, were bubbles that prevented their students from being exposed to the realities of their surroundings and only served to teach them English and how to be part of an exclusive elite. As the director of Bogotá’s Marymount, she decided to shut down the “Escuelita,” a badly maintained area on the school’s campus that was used to provide low quality education to low-income families from the South of the city. Instead, a year later, she opened a new Marymount “branch” in the El Galán neighborhood in the South of the city, with the intention of offering an academic program as strong as the one offered to the rich girls at the Marymount campus in the North. However, she and her teachers quickly realized that they were very distant from the reality these girls and their families were living — they noticed that an American nun, who had worked in the Bronx, was the only one who had been able to build a close and natural relationship with this community, despite not even being Colombian. Committed to improving this situation, Mother María del Consuelo enlisted the help of the mathematician Germán Zabala, who had been exposed to the work of the psychologist Jean Piaget in France, and had returned to Colombia with new and innovative ideas about pedagogy. Zabala was an atheist and a Marxist, but, thanks to the admiration he had for the radical Colombian priest Camilo Torres, he recognized the important role of catholicism in Colombia, so he offered to help the nuns and work for the school for free, accompanied by some people he knew from Universidad Nacional. Together, they created the school’s pedagogical program known as Modelo de Educación Integrada (MEI).

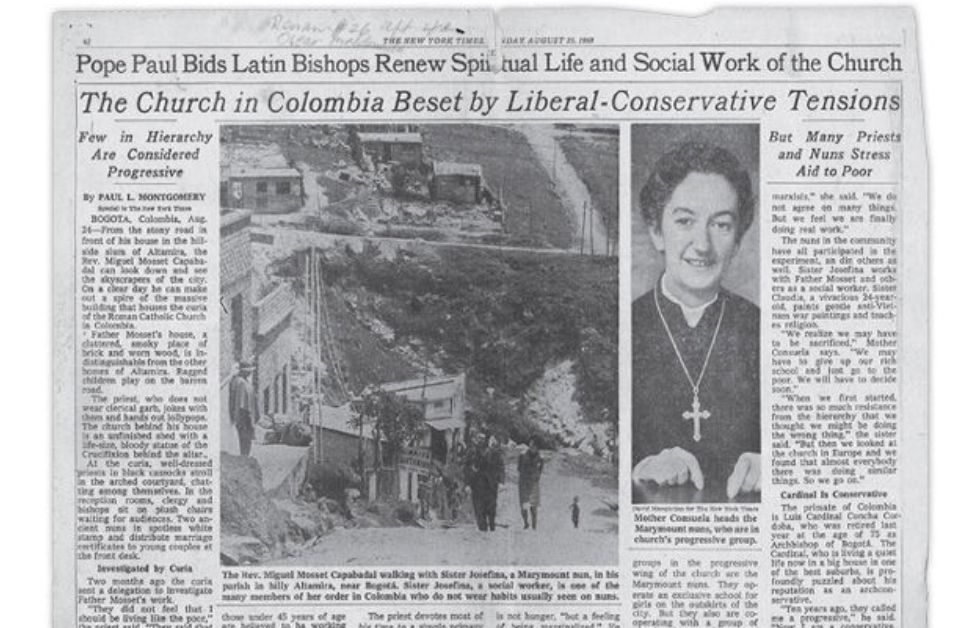

At this point, the parents of the Marymount of the North, who were mostly conservative, started to be alarmed, saying that the nuns wanted to turn their daughters into communists, even though María del Consuelo and the other nuns were simply following the mandate of the Second Vatican council and, well, working to remain connected to the changing world outside. This is when, in 1968, in the midst of the seismic political and social revolutions taking place across the globe, El Tiempo, the most prominent newspaper of Colombia, published on its front page an article entitled ¿Infiltración Marxista en el Marymount? The article, written by an influential conservative journalist, came out the day after the school had presented the traditional Song Contest, a competition of musical plays created by each of the classes in the high school grades. The graduating class had decided to present their play in Spanish, as opposed to following the tradition of doing it in English, indicating that they were not interested in winning any award, but wanted to perform in Spanish so that they could communicate a message. The performance was a fantastic and well-produced play that dealt with political matters, social conscience, and class struggle — basically all the things that upper class girls in Colombia were not supposed to know or have an opinion about. The scandal took on epic dimensions: even The New York Times and the Corriere della Sera published articles about it. The teacher who helped organize the Song Contest was fired, and all the nuns of the school informed Mother María del Consuelo, who was working in Medellin at the time, that they were so disappointed by the reaction of the parents and the press that they wanted to go on strike. Mother María del Consuelo called New York for help, but was told to travel directly there to discuss potential solutions in person. Once in New York, they called Rome but were told to travel there. And it is in Rome that the congregation of nuns of the Sacred Heart of Mary, discouraged and frustrated, decided that there was no one who could run the Marymount in the North of Bogotá, so they decided to close it, and only continue with the one in the South.

In a way, I was not completely wrong when I thought that my school was located at a far edge of Bogotá. Not only did it exist in a geographical corner of the city, it also, and most significantly, existed in an exclusive tiny corner within the socioeconomic landscape of the country. My school, as was the case with its older version, had the daughters of some of the most influential political and economic families of the country as its students. However, not everyone was rich or a descendant of an economic empire or a political dynasty. There were also girls like me, whose families didn’t have any influence or relevant role in the social, political, or economic mechanisms in the country, but hoped for a good education for their daughters. And yet, we remained in an isolated bubble protected by a brick wall and “safe” from what may lie beyond it.

I now understand that the notion of trouble with which I had naively associated these nuns could have been interchanged with the word struggle, and that paths that could have appeared in contradiction or opposition to each other could in fact be intricately intertwined.

At the end of 1969, frustrated and still in search for social justice, after twenty years of being a nun, of never having considered herself a Marxist, and of never having believed in the armed conflict, Mother María del Consuelo joined the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) and started a new chapter of her life as an undercover member of the armed guerilla.

Part 2 of Nuns, Witches, and Teachers will be published on June 7th, 2017.

- Leonor Esguerra and Inés Claux Carriquiry. (2011). La Búsqueda (E-Book, Santillana Ediciones Generales), Loc 35 of 4117.

- Leonor Esguerra, quoted in Rebel Girl (2012, February 13). Still searching for equality: Leonor Esguerra (Blog post). Retrieved from http://iglesiadescalza.blogspot.com/2012/02/still-searching-for-equality-leonor.html

- Leonor Esguerra and Inés Claux Carriquiry. Loc 972 of 4117.

Comments (2)

Millions upon millions of innocent humans have lost their lives in the name of organized religion:

https://www.thetoptens.com/atrocities-committed-name-religion/

sorry…

Excelente escrito. No solo informativo sino más real de lo que verdaderamente pasó en el Marymount. Espero la continuación.