Currents Within a Collection: Agnes E. Meyer

The Elise S. Haas Bequest: Modern Art from Matisse to Marini is on view at SFMOMA till June 2. Open Space is pleased to host a series of posts highlighting Mrs. Haas’s network of personal connections from SFMOMA Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture Caitlin Haskell and featuring graphics by designer Adam Machacek.

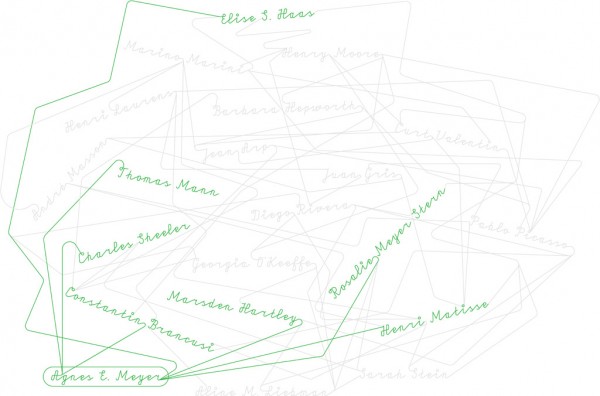

Agnes E. Meyer diagram by Adam Machacek. Click image to enlarge. Click here to view interactive Haas Bequest diagram.

Visitors to our current presentation of the Haas collection find an exhibition that unfolds across three galleries, each loosely dealing with its own theme. It opens with a gallery of portraits, or perhaps better put, a selection of early twentieth-century artworks that show a range of views on the necessity of likeness in portraiture. The second gallery (not without a few portraits itself) concern lyricism, a notion Elise Haas believed united her collecting practice. And the third and final gallery pairs works on paper and bronze sculpture by three artists Mrs. Haas knew personally and collected in depth—Henri Matisse, Marino Marini, and Henry Moore—so as to explore ideas they shared about the interconnection of two- and three-dimensional art making.

The Elise S. Haas Bequest: Modern Art from Matisse to Marini at SFMOMA featuring Charles Sheeler’s Untitled (La Négresse Blonde), 1945 (left), and Constantin Brancusi’s La Négresse Blonde, 1926 (right); Photo: Ian Reeves, 2013

The first gallery also introduces us to Agnes E. Meyer, Elise Haas’s maternal aunt by marriage. A mentor to Elise as a collector and patron of the arts, Agnes Meyer was a supporter and friend to many members of the Paris and New York avant-gardes. Among her art-world associates in the years around 1910 were Francis Picabia and Marius de Zayas (who worked with Meyer as an editor of the early Dada magazine 291), photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, painters Max Weber and John Marin, and Gertrude and Leo Stein. Of particular relevance to SFMOMA’s painting and sculpture collection is Meyer’s friendship with the Romanian-born artist Constantin Brancusi. The story goes that they were introduced by Steichen around 1912, and within a few years Meyer was among Brancusi’s earliest American advocates and collectors. Over their decades-long friendship, Meyer assembled a choice collection of five Brancusi sculptures, including La Negresse blonde (1926), which she and Elise Haas gifted to SFMOMA shortly after the artist’s death.

291 throws back its forelock by Marius de Zayas, March 1915 (left); “Mental Reactions,” a collaboration between Agnes Meyer and Marius de Zayas that appeared in the magazine they co-edited, 291, in April 1915 (right)

La Negresse blonde was the first work by Brancusi to enter SFMOMA’s collection and remains a foundational work within our sculpture holdings. In the current exhibition we show it alongside a photograph of the sculpture made by the American artist Charles Sheeler around 1945. The sculpture’s title refers both to Brancusi’s model, an African woman he met in Marseilles, France, and the shimmering yellow metal he used to evoke her striking presence. As one sees in the work, he reduced her features to lips, a chignon, and a zigzag form at the back of her neck. The similarly elemental three-part pedestal, comprising a cylinder, Greek cross, and limestone base, might be read as the figure’s body, shoulders, and neck or, it might simply be understood as a materially direct and eclectic platform for display.

Meyer’s enthusiasm for Brancusi’s work was infectious. As she wrote in 1953, “My friendship with Brancusi was later shared by my whole family and has lasted to this very day, because we all, including every one of the children, love the man’s quizzical, witty and profoundly honest temperament as well as his art.” Brancusi, in turn, thrived under the Meyers’ patronage and generosity. As a guest of the family in Mount Kisco in 1926, Brancusi carved a base for Bird in Space, supposedly working in the garden as the children looked on. Meyer likewise seems to have had the familiar habit of inviting guests to Brancusi’s Paris studio, as we learn in a letter informing Brancusi she would be paying him a visit with “a friend of Steichen and also of Mrs. Picabia” and promising to bring him “an old bottle of champagne that I found the other day,” a token for his hospitality.

Artists at Mt. Kisco, 1912; unidentified photographer. Abraham Walkowitz papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Description: Group of artists seated on the ground, among the trees.

Identification on verso (handwritten): Left to right – Paul Haviland, Abraham Walkowitz, Katharine N. Rhoades, Mrs. Alfred Stieglitz, Agnes Ernst (Mrs. Eugene Meyer), Alfred Stieglitz, J.B. Kerfoot, John, Marin. Property of Walkowitz family.

Published in: Archives of American Art Journal v. 6, no. 2, p. 15; v. 40, no. 3-4, p. 36

Charles Sheeler, Study of the Brancusi sculpture “Portrait of Mrs. Eugene Meyer.” © The Lane Collection. Photograph courtesy of the Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC.

Meyer was sometimes known as “The Sun Girl,” a nickname that played on her radiant personality, and as the twentieth century progressed she became increasingly popular subject for artists. In 1914 De Zayas’s drawing “Mrs. Eugene Meyer, Jr.,” appeared in Camera Work, and a decade later the composer Erik Satie dedicated a short piece of musique d’ameublement to her. In 1929, when Brancusi caught wind that a sculptor from a rival stylistic camp, Charles Despiau, had made a portrait of Agnes Meyer, he set out to make a sculpture of his own—an alternative representation that would show Agnes a truer depiction of herself than Despiau’s portrait bust. The resulting sculpture, a monumental work in black marble, was completed in 1930. Now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, the sculpture is as beguiling as it is evocative of its sitter. And like La Negresse blonde, it was also captured by Sheeler in photograph.

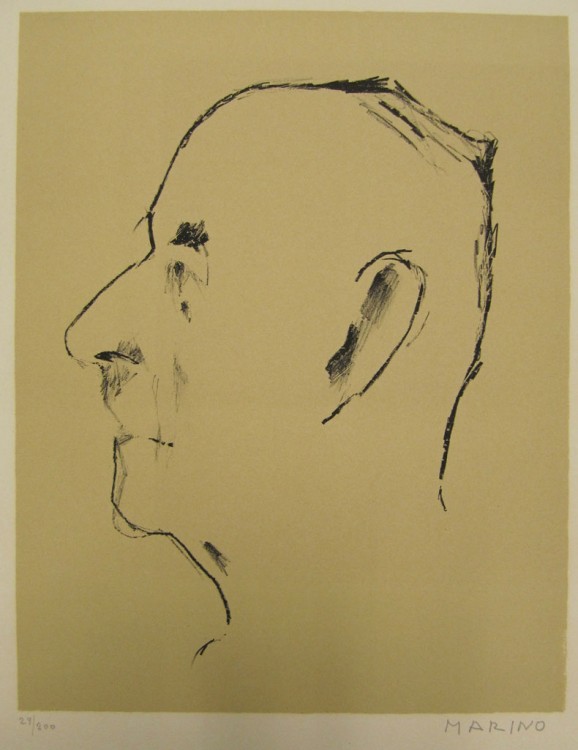

Agnes Meyer was also a pioneering journalist and accomplished translator. She translated letters by Vincent van Gogh for 291, but her most notable translations were of the work of Thomas Mann, with whom she corresponded extensively. “I turned toward [Mann’s] works with as much or as little reason as a plant turns toward the sun,” she once wrote. Visitors may notice that the Haas exhibition contains a lithographic portrait of Mann by Marino Marini. The portrait is unusual for a couple of reasons. First, Marini is best known as a sculptor, and not terribly well known as a printmaker. Second, his most recognizable work tends to use the horse, as opposed to a human figure, as its motif. But to me this relatively modest contour drawing has become one of the physical embodiments of the commitment to the arts shared by Meyer and Elise Haas. And in that way it holds a place alongside La Negresse blonde as an object that allows us to observe the networks and traditions in which Haas hoped to operate as a collector.

A few final notes on Mrs. Haas and Marini. Elise had an especially close relationship with the sculptor and great sensitivity to his powers of representation. She described her time visiting him in Italy as unforgettable and rewarding and collected multiple works on paper as well as his sculpture in the round. Asked if she felt Marini’s drawings made him a sort of painter, she replied, “Well, no, he’s not a painter, but all sculptors make drawings. . . . I really think that often I prefer a sculptor’s to a painter’s drawings, because first of all I love sculpture, and secondly, they have a certain solidity and strength that very often other drawings don’t.”

Marini’s bronze portrait of the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, which we show in this exhibition adjacent to the portrait of Mann, synthesizes several of Mrs. Haas’s interests—music, portraiture, and sculpture. Around the time Marini was awarded the prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, Elise purchased the work from the noted New York dealer Curt Valentin—in whose gallery Marini and Stravinsky first met. Haas presented the sculpture to SFMOMA in 1952, and it was the first work by Marini to enter the collection. Mrs. Haas and Marini remained friends decades after this purchase, and in the 1970s she proposed that he make a portrait head of her husband, Walter Haas, Sr. Due to difficulties arranging a sitting in Milan and the impracticality of working from photographs, the project was never realized. But the portrait of Stravinsky allows us to imagine what might have been.

Caitlin Haskell is SFMOMA assistant curator of painting and sculpture.

After collaborating on several projects, graphic designers Adam Macháček, Sébastien Bohner, Petr Bosák and Robert Jansa (formerly Welcometo.as and Advancedesign.org) started a new partnership called 2011 Designers, with the conceit that the name will change annually (www.2013designers.com). They have engineered a process of working together online while in separate locations – their studios being located in Berkeley, California; Lausanne, Switzerland; and Prague, Czech Republic. Their work includes printed publications, exhibition design, type, posters, and illustration, for clients mostly in the field of culture.

For more on Agnes Meyer see: Sidney Geist, “Brancusi, the Meyers, and Portrait of Mrs. Eugene Meyer, Jr.” Studies in the History of Art. 6 (1974): 189-212; Douglas K. S. Hyland, “Agnes Ernst Meyer, Patron of American Modernism,” American Art Journal (Winter 1980): 64-81; Agnes E. Meyer, Out of These Roots (Boston: Brown and Company, 1953); Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender & Identity (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998). Follow the Currents Within a Collection: An Alternative History of the Elise S. Haas Bequest series here.