Proposal for a Museum by Ahmet Öğüt: Artifact (hereafter referred to as the work of art)

Carl Andre, 3rd Steel Triangle, 2008 | Ahmet Öğüt, intervention n.1: 2 tape measures, 2011 (installation view, Fondazione Giuliani, Rome)

How can we grasp the relationship between an institution and its collection of objects? One indication might begin from one dictionary definition of artifact, whose example of usage reads, “Hundreds of unidentified artifacts are stored in numerous rooms beneath the museum.”

There are two main points to this instructive example. It tells us first that artifacts are somehow naturally “unidentified”; another assertion is that they number in the hundreds.

The notion of this unknown quantity reminds me of my recent visit to Tate Stores, the Tate Museum’s storage space on Mandela Way in London. The scale of the storage, the sheer number of seen and unseen artworks, was simply enormous, in a place where over 65,000 works are kept and tracked at all times by sophisticated logistical teams. Some popular artworks are sent on loan often, while others remain unseen for many years. I had a similarly strange feeling in 2007 when I visited Frac des Pays de la Loire. There you encounter alienated pieces of museum architecture in the middle of nature, while the basement is similarly full of unseen artworks by well-known artists. It was apparent that these had been in storage for a long time. It looked like a well-designed bunker for works of art that might only resurface above ground after humankind has disappeared.

Carl Andre, 3rd Steel Triangle, 2008 | Ahmet Öğüt, Intervention no. 1: 2 tape measures, 2011 (installation view, Fondazione Giuliani, Rome)

Regardless of the kind of cultural or socio-political meaning a work of art manages to produce, most museums treat them as just such artifacts. In his essay “Contemporary Art and the Museum in the Global Age,” Hans Belting considers the Vatican Museum as a case in point. Pointing out that the museum did not start as an ecclesiastical repository but as a collection of classical statuary, Belting remarks that the sculptures of ancient gods in the collection were, at a certain point, no longer identified as unacceptibly pagan. Instead they were redefined simply as works of art. (See Hans Belting, “Contemporary Art and the Museum in the Global Age,” Contemporary Art and the Museum: A Global Perpective, eds. Peter Weibel and Andrea Buddensieg, Ostfildern, 2007.) Perhaps we are at a new juncture today, where artworks become artifacts again, during their long periods of storage, and rest in some basement or warehouse.

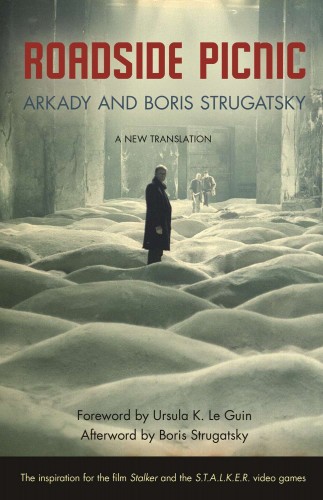

Last year artist and friend Heman Chong suggested that I read Roadside Picnic, a science fiction novel published in 1971 by Soviet-Russian authors Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.

In the novel, the character Dr. Valentine Pilman compares an extraterrestrial event (called the Visitation) to a roadside picnic happening on some road in the cosmos. Neither the Visitors themselves nor their means of arrival or departure were ever seen by the local population. The artifacts the Visitors left behind — garbage, discarded and forgotten things — were understood by humans as supernatural, displaying strange and unidentifiable properties. Today museums (alongside other socio-cultural producers) appear as Visitors of a similar kind. (Though to be sure, nowadays some of our artworks are supernatural, with strange and unidentifiable properties immediately upon going public.)

So, turning to the prospect of my proposal, what should we worry about first? That in the near future there will be too many artworks, creating a kind of ecological crisis of overpopulation? Or should museums concern themselves with how to relate to a general public based on how we produce contemporary art today? My point is that both artists and museums should think about what to do with the artwork, before and after it is produced, and especially, once it is acquired. The real life of an artwork starts only at that point, including the various stages of waiting in storage, being prepared and displayed, and finally as the public interacts with them.

Thus if we just take a moment to look at museum loan forms, we easily understand the state of mind of a museum. We should constantly remind ourselves that a collection is a living thing and a museum is not a graveyard.

With this in mind, what is necessary is a progressive museum with a risk-taking and self-critical team, to oversee the awkward transition between artifact and cultural or artistic meaning. A progressive museum has departments operating equally together. It knows the importance of education and community departments and engages with them sincerely, not symbolically. A progressive museum is open to intervention not only by itself but also by the audience. Here I don’t mean intervention as adaptation, as in converting a 16mm film to DVD and projecting it that way, or excessive renovations of a fresco or a painting and so on. On the other hand I don’t mean to suggest an attack that can create permanent damage. I mean a type of intervention that is not permanent, but using the art already existing in a given museum as a tool that could create new readings, understandings, misunderstandings, and new life for the collection. Such interventionary practice leads an artwork to a new set of ideas relevant to current socio-cultural contexts. By intervention, I mean reconnecting art with today’s public. This new type of museum must rethink the collection not only as model of display, but as a constant series of interventions. It should continuously challenge itself, instead of remaining dormant and helpless within its own secure bureaucratic milieu.

—

Ahmet Öğüt is an artist based in Istanbul and Amsterdam. Find grupa o.k. on Tumblr and read other proposals here.

Comments (5)

It’s not “have it your way” per se, but Visible Storage at the Brooklyn Museum (http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/luce/) is an attempt to show what is typically behind closed doors. However, in agreement with Öğüt’s point, this model could easily be considered akin to Lenin’s glass mausoleum.

We like this: http://grupaok.tumblr.com/post/20062144563/frederick-kiesler-painting-library-and-study-art

We agreed for a minute, Eleanor. But then we started to think it was a little like Burger King’s “have it your way.” Or a giant vending machine? Mixed feelings.

On-demand artwork viewing is an excellent proposition

While reading this I pictured an art museum that incorporated their storage into a giant, robotic, glass-cased wing of their museum, where the visitors could view works on demand through the glass – something between this automated parking garage and the design of the LBJ Library. Could be great.