Memoirs of a Circuit Judge

I find myself drawn to Open Space when I have a story to tell about “behind-the-scenes” experiences I have in my role as a curator in rural Northern California. I was recently invited to Redding to judge the 62nd Annual Student Art Show at Shasta Junior College. It was an experience that I am still thinking about two weeks after the fact.

I find myself drawn to Open Space when I have a story to tell about “behind-the-scenes” experiences I have in my role as a curator in rural Northern California. I was recently invited to Redding to judge the 62nd Annual Student Art Show at Shasta Junior College. It was an experience that I am still thinking about two weeks after the fact.

Back in the days when the NEA was a tad wealthier than it is today, there was a wonderful program that sent practitioners around the country to do site visits at peer organizations. The ostensible reason was due diligence to assure that federal money was being spent according to the rules, but the true purpose was to seed the field, to have leaders and activists meet and share ideas and perhaps spawn collaboration. It was a magnificent success, and in my case, as a frequent site visitor for artist-run organizations all over the U.S., it added to my education about how the arts are manifested and maintained in particular communities. One of the many insights I came away with on these visits was [alert: sincerity ahead] that art workers are incredibly altruistic, innovative, hardworking, and smart, and are almost always underpaid, overworked and under-appreciated. One got on the plane to go home wishing that everyone could get every penny and more that they requested in their grant applications.

This memory — most NEA site visiting was ended twenty years ago — was with me as I drove from my home in Oakland some four hours north to Redding. I’d been asked to give a lecture about my career, and to sort through 500 entries to find a couple of dozen to constitute the exhibition. I hoped for the best but feared the worst; I’ve been in situations in which I could not find enough even vaguely interesting works to make a show. It’s hard for me to turn down this kind of gig — it’s extra cash that I feel compelled to squirrel away in what’s left of my “prime earning years,” a phrase I think I heard on the radio once and have never been able to expunge from my conscience. And there’s a paranoia, a feeling that if you ever once turn down the chance to be a visiting speaker/juror, you will never be asked again. Of course, there is a certain pleasure in the honor of out of the blue being asked to share your knowledge. There’s something incredibly touching about the tacit contract at hand with these young or emerging artists: “I will show you, a perfect stranger, my first efforts, for which in exchange you will be neither patronizing nor unkind but rather, generous and encouraging.”

Redding apparently is a glimpse of rust belt America in California. Mining and timber industries are played out, replaced by drug dealing, poverty and homelessness, and the 7th ranking crime rate in the U.S. As the California educational system is being dismantled by billions of dollars in budget cuts, junior colleges are hit the hardest. Shasta — located on a lovely, large, grassy campus suggesting happier days — has seen the ranks of its full-time art teachers reduced from eight to two. I had dinner my first night in a nice restaurant in a strip mall with three faculty members: David Gentry, my host, a youngish artist; John Harper, recently retired chair of the department, and his wife, Mary; and a long-serving theater professor, Robert Soffian. What could be a greater terror for a shy person like me than to have dinner with four strangers to whom one might not have a thing to say? I was greatly relieved that all four could not have been nicer: informal, funny, smart, and very passionate about the arts. I got back to my hotel room with that familiar NEA site visitor quiver in my bones: yet another lesson, a reminder, of the punishment inflicted by our society on people who choose to teach, make, and present arts as a career. Of course in many ways it’s a privileged life, but honestly, who wants to be asked to do more with less year after year after year … for almost thirty years, as have Harper and Soffian. I also met Susan Schimke the next day, the other tenured teacher along with Gentry, who is the painting teacher. More on that soon.

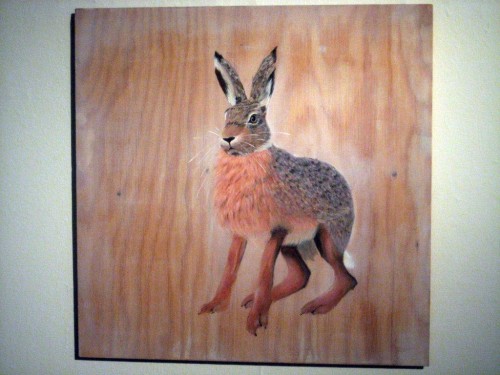

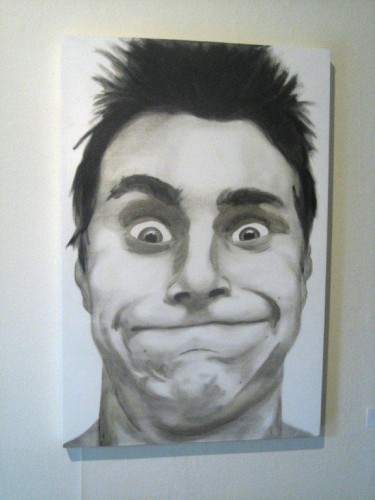

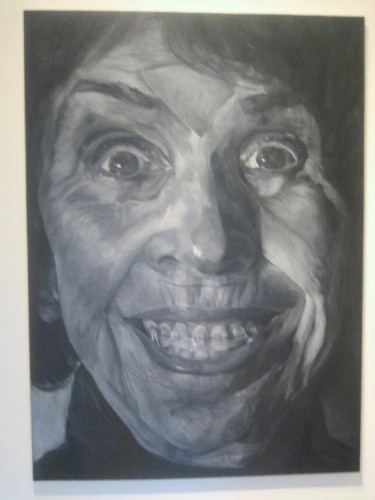

My talk went well the next morning — I don’t think I’d ever given a lecture at 9 a.m. before. One consistent truth I’ve learned is that you can’t tell how your presentation is going by the vibe you pick up in the room. It’s usually deadly. It’s the question-and-answer session afterward where you find out if you’ve touched people, and this one was quite lively, with good questions. I had prepared about 75 minutes but had to stop after about 40 so that was odd, but the first question was, “Can we see the rest of your slides?” So that was great. Afterward I began to look at the submitted art. It literally filled four classrooms. The largest group was drawings and prints, and that took the most time. I asked if there would be a problem with a large, very precise, and very successful charcoal drawing of a cock and balls; they assured me it would be OK. I found around a dozen strong pieces to show, no problem. Then ceramics and glass: not much there. I picked three. Sculpture: literally nothing. And then the miracle occurred. I walked into a large room filled with around 50 paintings. I could’ve shown half of them with no problem. Either Schimke’s teaching (and others’) is very special, or there is a population of born painters in the area (or both), but it was as much fun as I’ve ever had jurying an open call show, moving through that space. So, you just never know; I thought these isolated JuCo artists the equal of any anywhere I’ve taught or judged, and better than many. Here are four of my favorites:

Comments (3)

I’m so gald I found this site and this article. Thank you for your down to earth writing and for sharing your intelligent insight. I love the photos.

Renny, I grew up in Redding, then Sacramento then San Francisco. My experience was that Redding thinks Sacramento is the big city, Sacramento thinks San Francisco is the big city. What strikes me is just how different the cultures are even though they are all in California. I am sure though, like with what happened with UC Davis, if the conditions were right (and the money was there) a small program could attract great teachers in a small town and have a big impact.

Keep on truckin’, Renny.

Mac