Highway '71 Revisited

Today’s post on Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots, by SFMOMA Managing Editor of Publications Judy Bloch, refers to Picturing Modernity, SFMOMA’s regular rotation of our photography collection, as well as State of Mind: New California Art circa 1970, currently on at the Berkeley Art Museum. Highway ’71 Revisited cross-posts today at the excellent BAM/PFA blog, blook.

No sooner had Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots (1971–73) come off the wall at the close of SFMOMA’s 1970s-focused installation of Picturing Modernity than the work appeared in the Berkeley Art Museum’s exhibition State of Mind: New California Art circa 1970. I like to think of the Boots shuffling across the Bay Bridge under cover of night, perhaps during the President’s Day weekend, when the upper deck was closed for construction. The reality of course is that multiple editions of this piece exist.

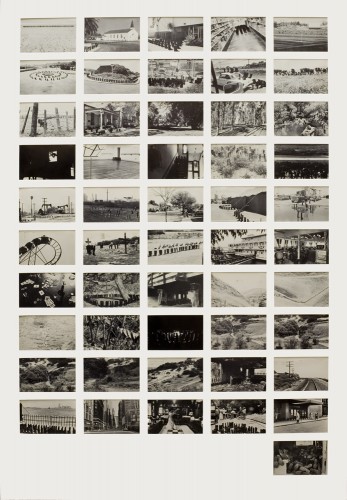

Eleanor Antin, 100 Boots on the Way to Church, from the series 100 Boots, a set of 51 photo-postcards, 1971

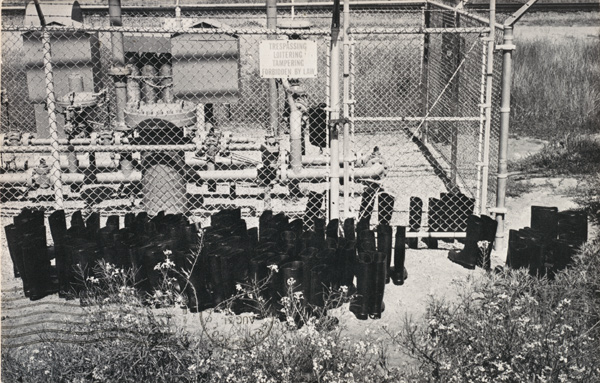

100 Boots originated as a work of mail art consisting of 51 postcards that Antin sent in succession to about a thousand people. Each card pictured a scene in an ongoing picaresque narrative that the artist staged and (with photographer Phel Steinmetz) shot on sites not far from her San Diego–area home. The protagonist was the eponymous bunch of boots, whose hero’s journey led out from an idyllic but soulless beachfront suburb (100 Boots on the Way to Church shows telltale palm trees), up hill and down dale and into an antiwar protest (100 Boots Trespass), the draft and the Vietnam War itself (100 Boots on Reconnaissance), and reentry in New York Harbor. Will 100 Boots make it in the Big Apple? Don’t know — almost immediately 100 Boots Go on Vacation, their piled-up soles showing out of the back of a van. In 1973 100 Boots, the work, entered the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and made art history.

To say that I get a kick out of 100 Boots would be to make a bad pun, and besides, Antin’s photographic tale of unmanned footwear on the go, beyond being droll and endearing, is unsettling. When I first saw it, its antic clarity moved me almost to tears. I want to imagine why.

At SFMOMA the pictures were shown window framed, five across, 10 down (plus one), the effect being like a filmstrip or even a View-Master. I think this is what initially attracted me to the work. Being a displaced film person (DFP) — I cut my teeth in the arts as film notes writer for the Pacific Film Archive — I pathetically gravitate toward anything sequential on the museum walls.

Eleanor Antin, 100 Boots on Reconnaissance, from the series 100 Boots, a set of 51 photo-postcards, 1972

Moreover and most importantly, in both venues the pictures are shown without the identifying titles I’ve cited above, which evidently appeared on the back of each postcard (they are reprinted as such in the book 100 Boots that Antin published with Running Press in 1999). As a purely visual experience, the story in the gallery is vague, suggested rather than told, with the possibilities for both humor and menace to be supplied by the viewer.

Black-and-white lends the images a scrappy quality, but it might as easily have been a financial necessity for Antin (1,000 x 51 + postage …). To me, though, B&W immediately signaled period piece and, in this instance, a far and hollow distance from the present. I was reminded of the time my son earnestly asked my mother if the world was black and white when she was his age.

For a child of the sixties, as I was, the world was black and white in 1971. The war was an abomination that, thanks to the draft, threatened youth on the home front to a degree unimaginable today. Like the Boots, we sought refuge in the good — At the Pond, In the Wild Mustard, On the Road. But Antin’s pictures capture just how hapless this attempt at escape was, at least for some. For every meadow there is a barbed-wire fence.

A casually brilliant study in negative space rather than absence, 100 Boots is really about synecdoche, where the part represents the whole: The Invisible Man made visible by his boots. The emperor without his clothes, or in Bob Dylan’s version of that tale, the president standing naked, save his galoshes. Boots, specifically army-navy surplus boots, are made for marching, whether in war or for peace. “Let me die in my footsteps / before I go down under” (Dylan again). Soles make the man, as in Philip Guston’s autobiographical paintings. Shoes suggest man’s fate, the one he carelessly walks into.

Judy Bloch

For Steve, who Took the Hill.

Eleanor Antin, 100 Boots Taking The Hill (1), from the series 100 Boots, a set of 51 photo-postcards, 1972

Judy Bloch is managing editor, publications, at SFMOMA. Previously she was publications director at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Eleanor Antin will read from her coming-of-age memoir, Conversations with Stalin, at BAM/PFA on Friday, May 11.

Comments (1)

Oh Judy, How we miss you!