Wayne Koestenbaum at SFAI

On Wednesday, April 11th, Wayne Koestenbaum spoke at the San Francisco Art Institute as part of the Visiting Artists and Scholars lecture series curated by Glen Helfand. That afternoon, on the other side of the city, and with one eye on the clock, Kevin Killian visited my Fundamentals of Creative Reading class at San Francisco State. To transmit the essence of poet’s theater, Kevin invited the students to act out the reality-bending Love Can Build a Bridge, which he cowrote with artist Karla Milosevich. There were just enough parts for everyone in the class, including me — I played artist Donald Judd’s lawyer. The play is set in Marfa, Texas, right after the death of Donald Judd, and his family — singer-wife Naomi Judd and daughters Ashley and Wynonna — have gathered for the reading of the will. Other characters include actor Judd Nelson and performance-art duo Marina Abromovic and Ulay. None of my students had ever heard of any of these people, the characters they were now playing, but Kevin explained dutifully that Richard Serra was a famous artist and everybody called Judd is famous in his or her own way. The plot of Love Can Build a Bridge turns on the contested video will of Donald Judd (played on DVD by the late filmmaker George Kuchar). Kevin forgot to bring the Kuchar video, so he played Donald Judd himself. The students gave some amazing performances in our Humanities Building classroom, where our only props were a table, which served as the bar for Roy’s Cotton Club, and one of those chairs with a built-in desktop for the Wandering Stranger (Lucinda Williams in disguise) to sit in.

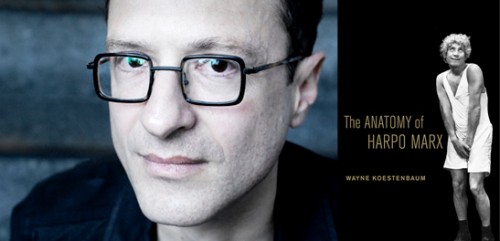

We left State a little after 7:00, raced down 19th Avenue to Geary, etc. — and arrived at SFAI in time to catch the tail end of the first portion of Koestenbaum’s talk, a 15-minute preamble on the topic of concentration. “The act of attentiveness is more important than the object being attended to,” said Koestenbaum. This deep attention leads to an exaltation akin to an orgasm, and the adoring focus of the critic is a sort a freeze before exaltation. Then, in honor of his new book, The Anatomy of Harpo Marx (University of California Press), Koestenbaum read meditations about Harpo, accompanied by film stills. Film history is so slippery I wonder if people even know who the Marx Brothers are any more, but they were a comedy trio from the age of vaudeville who broke into pictures at the beginning of sound: three Jewish brothers with amazing timing and wildly different personalities — which was part of the comedy, that brothers could be so different. Groucho was the witty, sophisticated one; Chico, the faux-Italian pianist; and Harpo was about as oddball as a human could be — and he never spoke on film, just let his face and rubbery body and his horn speak for him.

Koestenbaum waxed lyrical about Harpo’s harp playing, the Y-shaped crack of his ass, his libidinal excess, the weird history of his silence. When Harpo was a young performer, a critic didn’t like his speaking voice, so his mother decided that henceforth in the family act, Harpo would never speak. Referencing Kant, Koestenbaum lauded Harpo’s “purposive purposelessness.” He compared Harpo’s glorious extraneousness to George Kuchar’s relation to good filmmaking. The Bay Area is still in mourning over Kuchar’s death last September, so Koestenbaum’s reference struck a chord. Kuchar, who taught at SFAI, is known for no-budget, kinky fantasy extravaganzas, often made as class projects. Kuchar had such an outsider aura about him that some students thought he was the janitor. He was a regular at Karla Milosevich’s holiday potlucks, and at a couple I attended, when dinner was over, guests would head downstairs to the flat-screen TV, where George would “premiere” his latest movie. I remember wrapping myself in a fake fur blanket that happened to be lying beside me, watching Kuchar’s scantily clad students writhing on the screen, and thinking I’m so happy to be living this life.

Throughout the lecture, Koestenbaum repeatedly returned to the erotics of contemplation, and the relationship between writer and subject. He evoked Julia Kristeva’s pairing of loving the object with devouring it. Himself a noted poet, novelist, teacher, and essayist, Koestenbaum spent four years staring at these film stills. To survive the difficulty of writing prose, he said, you need to be awake in the middle of a sentence, to be fully present within the web of syntax — or as Barthes wrote in The Preparation of the Novel, to enjoy the amber of being within syntax. Through Koestenbaum’s eyes, Harpo, while made very real — a skilled actor/musician with a history and career trajectory — became a dream figure onto which we could project our own marginalization, muteness, longing for purity. “I love Harpo. That’s a fact,” Koestenbaum said, with zero irony.

Afterward, a handful of us headed over for a late dinner at Original Joe’s, across the street from Washington Square Park. There’s a kitschiness to the restaurant, the way it’s spanking new yet its decor and menu mimic an old-time Italian joint. As he slid into our huge, curved booth, Koestenbaum caressed the leather and exclaimed, “I’ve never seen red leather this shiny!” It struck me that it’s not Koestenbaum’s highly trained intellect that is the source of his genius — it’s the way that intellect is softened by his unmediated delight in what the Taoists call “the ten thousand things.” In his lecture, the way he put it was that the writer falls in love, over and over again, with various constellations. A white-aproned waiter appeared, and Koestenbaum ordered a Sauvignon Blanc.

Comments (3)

I’m so glad I’m living this life…with these people. Thank you all for this.

I also was at Wayne’s SFMOMA talk, and yes amazing, like—not listening to but—sitting in the center of a poem. Kevin has put on plays with a few people’s classes. He’s quite in demand. He’ll be presenting a couple of performances at SFMOMA in the upcoming year which I think will be really exciting.

That talk was very uplifting. He said numerous amazing things… I love this guy. Was very grateful to hear him speak last year at the MOMA in regards to the Stein’s Collect exhibit and was super stoked to have him speak hear and at City Lights! The ability to concentrate, to truly focus in, is something I believe has been lost on our community as of late. Hearing his remarks on commitment (on an excessive level), love and concentration had bits of my brain flying all over the room…

I s wish I could’ve been there to experience this reading of Love Can Build a Bridge… Ashley Wynonna Judd, the daughters of Don. Good one, Kevin!