Treasure Hunt

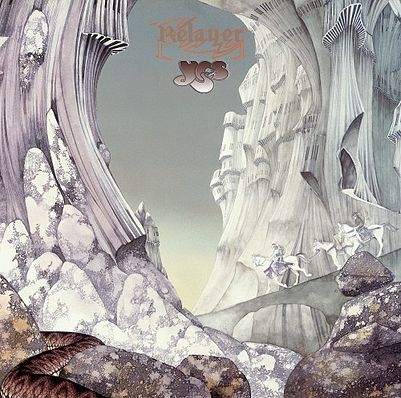

Whenever I feel surprise at having become an an art dealer, I remind myself that at 14 years old, like some suburban Medici prince, I commissioned my first work of art. For the grand sum of twenty dollars, or bag ‘o weed of same value, I got my friend Lance, who was something of an artist, and something of a hustler, to paint the cover of Relayer by the band Yes on the back of my denim jacket.

I had only one denim jacket with which to brand myself, and Yes seems an unlikely choice for a kid whose primary response to the world was “no.” But I made the commitment casually, the way a 14-year-old does, even though I knew that Yes was just the latest fling in a long line of musical infatuations, and that I would soon be repelled by the image. When you’re a kid, and you move on from a band, you don’t just let them go, you bonfire their albums because they stand for everything you are trying to grow out of.

As with so many boys of my generation, my first musical loves were the Osmond Brothers, Mormon dandies in white suits with white fringe, and the Jackson Five, 10 glittery lapels in seriously tight choreography. They were soon upstaged by the Monkees, who were conveniently delivered right to my bedroom every afternoon at 4, and the Beatles, whom I communed with for a long, long time. Then, along came the Beach Boys, who awoke in me a love for my future home, California.

Things picked up pace when I turned 12. I powered through a series of predictably unsatisfying affairs with the Eagles, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, and Boston. But just when the music was getting harder with Led Zeppelin, Alice Cooper, and Jimi Hendrix, I took a strange detour, that cannot be understood by anyone who didn’t live through the mid-’70s, into the jazz fusion world of Billy Cobham, Chick Corea, and Al Dimeola. That road bottomed out with the queasy ambience of Yes. The musical equivalent of a Carlos Casteneda novel, it was my last escapist affair before encountering Bowie, the Ramones, and punk rock, which would deliver me from my sneering, sarcastic youth into adulthood.

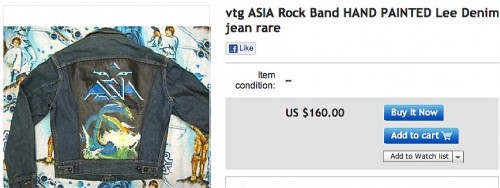

Before that, I was a teenage stoner in a big, unhappy house, and I loved to astrally project myself onto the fantastical landscapes unfolded to me in Yes’s spacey New Age music and graphics. Unfortunately, the trippy ambience didn’t translate into a jacket thing, and Lance’s strange denim concoction, which would stump even Dick Hebdige, got nudged to the back of a closet full of cuffed jeans, blue suede high tops and army surplus jackets. At some point my mother must have given it away, and it has probably since been resold on eBay as folk art.

It seems like, in America at least, art and music, not to mention clothes, have always gone together. The Abstract Expressionists painted to jazz, Warhol to the Velvets. In San Francisco we have the psychedelic poster to commemorate that brief moment when the Bay Area music, drug, and art scene ruled pop culture. For some reason, I never got into these posters despite the fact that I like some of the music, love art nouveau, and suffer from a slight case of horror vacuii. They just don’t call to me.

That all changed last week when a seller at the Alemany Flea Market turned up with a stack of large, brightly colored sheets of paper. I find a steady stream of amazing stuff at the flea market. I go almost every Sunday at 6 a.m. as though it were church. Aside from the pleasures of sharing space with a motley crew of misfits absorbed in the work of gleaning, I go there because I like having an alternative to the studios, galleries, and auction houses where everyone else in the business shops. The flea market deforms my inventory and collections in ways that make them less predictable. You really never know what’s going to pop up there.

Peeking at the corner of the colorful sheets in the trunk of the seller’s car that morning, I thought to myself, This is interesting. Probably some Pop art–era billboard selling soap. Because of unusually high winds, it was too dangerous to spread them out on the concrete, where I and everyone else could see them. Not wanting more useless historical detritus, which sticks to me like flypaper, I was ready to blow them off when the seller agreed to delay a sale until I could examine them in the safety and privacy of my own gallery. In the never-ending game of winners and losers at the flea market, where pushing, elbowing, and line-cutting are the norm, a private viewing means Scoreboard!

I want to say that laying out these twelve, approximately 5-by-3-foot, screen-printed sheets of paper in their proper order was like watching a butterfly emerge from a chrysalis. But that lackluster cliche so wildly underrepresents the neuronal clusterfuck that took place when this psychedelic poster mural by Robert Fried came into focus. Fried, along with Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, and others, pioneered the psychedelic rock poster in the late 1960s. I don’t know if he ever designed for Yes, but his LSD visions of extraterrestrial vistas made with intensely saturated colors would have fit them like a glove. Like some Proustian Madeleine, the mural put me right back on my teenage built-in bed, staring at the Larry Zox–style graphic my mom had had painted on the wall above, enjoying a druggy deliverance from the unpleasant tedium that was always me contemplating me.

This is the perfect flea market score. I rescued an important work by a now-obscure artist: Wild West was one of only two billboard-size murals at Fried’s 1973 retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum; and it combines, like no other work I know, the nose-in-page intimacy of an underground comic with the ambitious scale of manifest destiny and American advertising. I will eventually make a lot of money on it — how much depends on how scarce these are. Can’t be that many around! And by introducing the randomness of the flea market into my curatorial practice, I have overcome the predictability of my own habits and limitations, which is saying something.

I’m sorry if what started as a sharing has turned into a vaporous boast. But that’s the flea market. Half the reason people shop there is so they can tell their fish stories after. Scoreboard! But after so many years and so many fish, I’m more interested in the weird glimmers of strange knowledge that one espies there. You can develop all manner of expertise at the flea market, from knowing how to fix and operate obsolete tools to the ins and outs of 19th-century fraternity pennants. I always think when I get up in the morning that I’m going there to prospect for treasure; but as in some cartoon where the character digs a hole in his backyard and ends up in China, I always end up tunneling back to me.

Comments (1)

Love the discovery of forgotten, mocked or discarded and just plain lost to history. I paint upcycled denim jackets @paintedvisions on Instagram. I sell them to fund the teeth grinding moments when I move from craft to what I might wish to call my art. I find that joy in the beauty of junk, kitsch …a comfort of memory and distraction from impending fascism

I think I knew Steven and that old house in the 1980s. He was inspirational and introduced me to what would be a life long love of Sondheim