Paper Trail: Following Julia Goodman

Julia Goodman, Certain Is Nothing Now, 2008

When I saw this sculpture, crafted out of handmade paper, hanging in an alcove at California College of the Arts a few years ago, it stopped me in my tracks. The piece, with its multiple formal, material, and conceptual references to cycles, exemplifies, for me, what a teacher of mine once described as “the peculiar poignancy of aesthetic experience.” I visited the artist’s studio at CCA on several occasions. Back then, Julia Goodman’s practice revolved around making paper out of the junk mail she collected from her neighbors. Her studio was filled with screens stretched over wood frames, buckets of pulp, and molds to shape the pulp into paper sculptures.

Goodman is still creating poignant sculptures out of handmade paper (more about that in a minute), but of late, she has also begun to investigate “pre-paper technologies.” She has taken, more precisely, to making papyrus out of beets. She slices these root vegetables ultra-thin with a mandoline, arranges them in overlapping patterns, and applies enough pressure to laminate their fibers.

Julia Goodman, For Eva, 2011

She began growing her own materials to expand her color palette and the variety of available forms. From her garden in Bernal Heights, she harvests beets with names like Albino, Bull’s Blood, Cylindra. She puts every product of her labor to good use. She eats the beets that don’t make it into her artworks, as well as the greens, and composts any remnants. She finds this creative process, centered on the garden and the kitchen, deeply satisfying. Thought-provoking, too. “Growing the beets leads to thinking about what lies below the surface,” she says. “And about the variety of species nurtured by the earth.”

She is currently showing a series of works made from beet papyrus at 18 Reasons, a San Francisco gallery/community center that contributes to the creation of a sustainable food system through educational programs, exhibitions, cooking demonstrations, and tastings. Oh, yes, and beet-papyrus-making workshops. Some of Goodman’s pieces are mounted on glass and hung in the storefront window that overlooks 18th Street. These translucent panes of laminated beets vibrate with intense color. “There’s something astonishing about letting light shine through a root that grows in the dark, underground.”

Julia Goodman, detail of work exhibited in Radicle Papyrus at 18 Reasons, San Francisco, 2012

Julia Goodman at 18 Reasons, 2012

I asked Goodman about the title of a large framed piece, For Eva. “Eva Hesse was one of the first minimalist artists to explore the use of impermanent materials. She passed away because of the toxic materials she was using — fiberglass and polyester resins.” Goodman pauses and points to the beets. “This material, in contrast, nourishes me.”

In tandem with the cultivation of pre-papermaking techniques, Goodman continues to create sculptural pieces using paper pulp. She has, however, foresworn the practice of making paper out of junk mail, with its toxic inks and additives, and now experiments, instead, with making paper out of recycled bed sheets. The process brings to bear her research on the history of rag papermaking while satisfying a desire to infuse abstract art with personal content.

Julia Goodman, She Wrote Love Letters in 1971, 2011

“I rip old bed sheets up into small pieces, boil them to break down the fiber, and then take batches of raw material to Magnolia Paper in Oakland, where they create rag pulp for me. Back in my studio, I press the pulp into hand-carved wooden molds.” These rag-paper works explore handwritten modes of communication. “Handwriting on paper, in this digital era, has become archaic. I want to make the handwritten word more significant again by experimenting with materials and texture … Adding texture to communication is my aim both as an art-maker and a person.” One series draws on love letters written by Goodman’s mother to her father during their courtship. To make the paper, Goodman used her parents’ bed sheets. In this way, the materials and text are intimately bound.

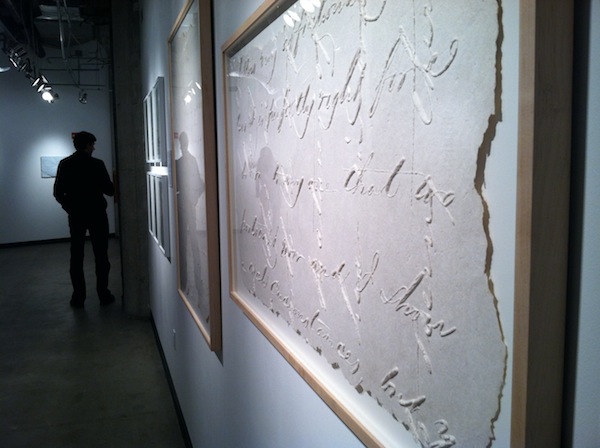

Julia Goodman, Amanuensis II, 2009

Another series explores a 19th-century letter-writing convention known as “cross writing.” Here, to conserve paper, a limited resource, the correspondent would fill a page with writing and then rotate it ninety degrees to compose another register of text, across the grain of the first. Goodman discovered examples of this practice at the Jack Mason Archive, during her J. B. Blunk Residency in Inverness, CA. She carved excerpts from the letters, backwards and scaled up, into wooden molds — hence, the title Amanuensis, which refers to a scribe employed to copy manuscripts. The paper cast from these molds makes an obscure form of penmanship fleetingly legible through a play of light and shadow. The sculpture’s imposing scale explodes the private ethos of cross-written correspondence. Nevertheless, the phrases Goodman has so painstakingly transposed preserve their mystery.

Several of the paper works are featured this month at Intersection for the Arts, in the group show In Other Words, which spotlights text-based practices.

Julia Goodman’s cast-paper sculptures at Intersection for the Arts

Comments (3)

So good to see how Julia’s practice has evolved since CCA and how the delicacy of her new work communicates with her earlier forms. Thank you!

Thank you for taking the time to correct this widespread misapprehension. I think you’ll agree that the artist’s point about working with toxic materials is valid, even if her example doesn’t hold up.

Tirza

To set the record straight: Eva Hesse’s brain tumor was not caused by a reaction to the toxic substances she used. Her doctor surmised that the tumor had already started to grow before she began using fiberglass and other polyester resins. I worked at Fischbach Gallery and was close to Eva at the time of her death.

Mac