Third Hand Plays: The Comedy of Automation

The comedy of automation is present in all electronic literature works that dynamically generate “literary” content without the work of a writer; we can see it in any number of works in the previous posts, particularly in the comedies of dysfunction, recursion, exhaustion, and association. I decided to create this additional category specifically for those works that generate content “on the fly,” and which might be admired more as marvels of engineering (of either the Steve Jobs or Rube Goldberg variety) rather than anything that could easily be called literary qualities. These works make no pretense to the lyrical — they are not trying to simulate an “I,” and don’t acknowledge the tradition of literary forms unless it be that particularly 20th-century practice, parataxis (the list) as open-ended form, such as in Joe Brainard’s famous anti-memoir I Remember, which is composed entirely of paragraphs long and short starting with the phrase “I remember …”

The comedy of automation is present in all electronic literature works that dynamically generate “literary” content without the work of a writer; we can see it in any number of works in the previous posts, particularly in the comedies of dysfunction, recursion, exhaustion, and association. I decided to create this additional category specifically for those works that generate content “on the fly,” and which might be admired more as marvels of engineering (of either the Steve Jobs or Rube Goldberg variety) rather than anything that could easily be called literary qualities. These works make no pretense to the lyrical — they are not trying to simulate an “I,” and don’t acknowledge the tradition of literary forms unless it be that particularly 20th-century practice, parataxis (the list) as open-ended form, such as in Joe Brainard’s famous anti-memoir I Remember, which is composed entirely of paragraphs long and short starting with the phrase “I remember …”

Parataxis figures prominently in Ron Silliman’s concept of the “New Sentence,” and can be seen as a companion development to the “constellation” in Eugene Gomringer’s phrase to describe concrete poetry — the former broke the bounds of the paragraph, the latter the stanza. The meeting ground of the two might very well be Pound’s Cantos, where the paratactic nature of his lyrical epic — the nonsyllogistic ordering of its luminous details — lent the poem a visual quality (enhanced by Chinese ideograms, but also the scattered diacritics of a dozen European languages). Charles Bernstein argues in “Pounding Fascism” that we can appreciate the Cantos against Pound’s over-determined political philosophy as an under-determined grab bag of glittering facts. Parataxis also appears quite frequently in conceptual art, and certainly a lot of conceptual literature, if not paratactic in structure itself, relies on a sort of “list-form” activity in its creation — the human as enacting an algorithm.

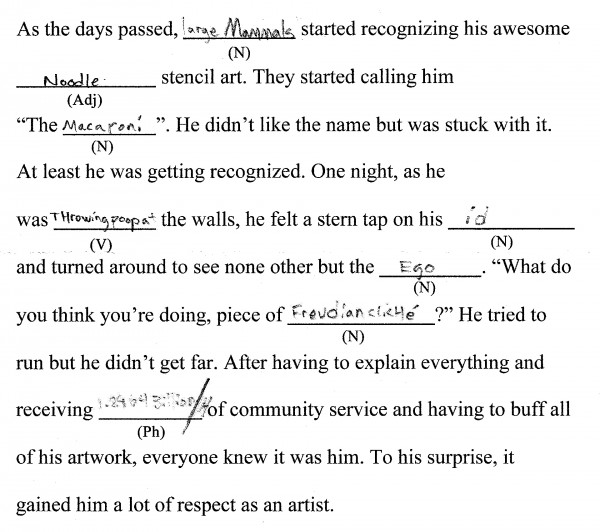

Lev Manovich, in his influential The Language of New Media, describes this very phenomenon in relation to video games: the game turns the player into the enactor of algorithms. Manovich writes about another element of new media culture brought on by what he calls the “database as symbolic form,” which he says tends to privilege the structure over the content (or the medium in McLuhan’s formulation) of the message. If the syntagmatic dimension of a sentence can be called its singularity in time and space — the words, the intonation, the volume, the resonance, anything related to the speech act at its most temporal and physical — the paradigmatic dimension is the diagrammatic shape of the sentence itself: the reduction (or subsumption) of the particulars of the sentence into its parts of speech, or further, into classes within these parts (nouns, for instance, which could be animals, toys, things your grandmother owns, nouns of Germanic origins, etc.). The syntagmatic dimension would be the last words your lover said to you before getting on the plane that crashed into the ocean two hours later; the paradigmatic would be the Mad Lib version of those last words — the empty blanks with their linguistic classes take precedence over the choices made in human situations. The syntagm is presence; the paradigm, absence.

“Billie Tweets” was a digital mash-up created in the immediate aftermath of Michael Jackson’s death. On the site, one clicks on the embedded YouTube video to start the music; tweets that contain individual words of the song start to roll down, in synch with the song, the right side of the screen. Though a quickie one-off, it puts the user in the interesting position of reading a series of unrelated tweets while also “reading” — if one reads what one probably knows by heart — the story of Billie Jean and Michael (who was, we are assured, not her lover). In the immediate aftermath of MJ’s death, no doubt the tweets were often concerned with him, but as time went on, of course, interest in his death would fade, though the words he used in “Billie Jean” live on. I haven’t researched how unique this little project is — surely Twitter feeds have figured in many digital art projects — but it’s curious that a Michael Jackson song also formed the raw matter of the greatest of the first series of Plunderphonics released by John Oswald.

“The Apostrophe Engine” and “Status Update” are two projects by the poet/media theorist Darren Wershler and the poet/programmer Bill Kennedy. The former takes a paratactic poem — each sentence starts with the phrase “you are …” — published by Kennedy in 1993 as the starting text, making of each phrase in the poem a live hyperlink. When one of the sentences is clicked, the program executes a series of Google searches for instances of the phrase “you are” and creates from the results another paratactic poem in the style of the original. “Status Update” (renamed “Update” for the book) is a little more mischievous: this time, Kennedy’s program collected Facebook status updates and attributed them to the accounts of dead poets (a list ripped from Wikipedia). “Jean Cocteau still can’t get over the fact that Bertie Wooster is a sex symbol. Jean Cocteau thinks he wants vodka. Iced with a bit of lime. Jean Cocteau watched a battle tonight and, as has happened so often this season, Habs win, Habs win, Habs win.” Of course, the latter project had to fold once Facebook didn’t require the “[name] is …” format for status updates (which made all of us, to a tiny degree, constraint-based writers). The former project, excerpts of which appeared as a book, Apostrophe, in 2006, is presently down due to a change in the Google API.

Other projects in this category include the “Pornolizer” (no longer live), which turned any web page into a particularly crude, infantile form of porn by switching out most of the nouns and verbs, and the “Shizzolator,” which took any web page and turned it into something that could be spoken by Snoop Dogg. The latter project was taken down due to the quasi-racist and misogynistic nature of some of the text; of course, algorithms don’t have morals or feel any understanding of basic humanistic issues — but do they have the right to free speech?

Chatterbots could be considered a form of this comedy. Even before “Racter,” which in its interactive form was a proto-chatterbot (a computer program that pretended to be human), was the program “Eliza,” created by Joseph Weizenbaum, which mimicked the behavior of a Rogerian therapist, one who doesn’t so much advise as rephrase one’s statements as questions: “I am not feeling well today. Why are you not feeling well today? Because I have to see Johnny. Why do you have to see Johnny?” etc. Legend has it that Weizenbaum’s assistant interacted with “Eliza” for hours without knowing that it was a program, and by the end of it was reduced to tears. More importantly, “Eliza” and projects like it might be considered a comedy of automation without the presence of a substantial database; the new content was merely reconstituted content provided by the human user.

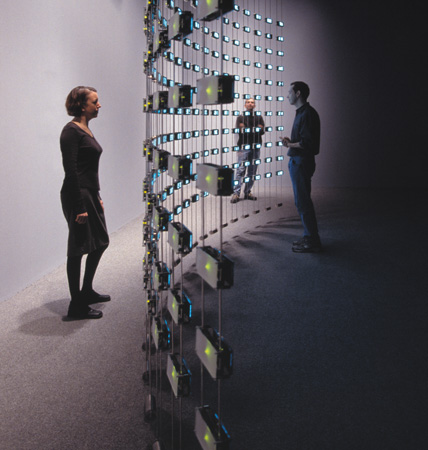

Mark Hansen and Ben Rubin’s installation “Listening Post,” launched in 2004 (the year Facebook was made available to select university students), was a series of small screens arranged in a wall that conveyed, ticker tape– (or Jenny Holzer–) style texts culled from internet chat rooms. A series of voice synthesizers “sang” parts of the texts to create something of a real-time opera based on the interests of humankind. Like many of the works in this category, “Listening Post” mimics the egalitarianism that stood behind such massive curatorial projects as “The Family of Man,” curated by Edward Steichen in 1955. The Wikipedia entry on this exhibit states that it contained “503 photos by 273 photographers in 68 countries,” which is certainly impressive; the comedy of automation preserves some of this humanistic content, but places the scale and frame of the project at the fore.