Erin Hyman: What Wine-Speak Says About Us

Designed in collaboration with renowned architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the exhibition How Wine Became Modern explores the visual culture of wine. It includes historical artifacts, architectural models, design objects, artworks and installations, including a “smell wall,” to probe many aspects of wine culture. Today, welcome Erin Hyman, on the language of wine.

“Petrol,” “noble,” “hamster cages,” “like cat’s pee on a gooseberry bush”—these are some of the outrageous-seeming wine descriptions that adorn the smell wall in How Wine Became Modern. Wine can hardly be consumed without a running commentary on its associations, it would seem; as wine critic Lettie Teague has put it, “I’ve enjoyed wine without food many times but I’ve never tasted a wine that was unaccompanied by words.”

Surprising, then, that wine talk—so pretentious and so often parodied—is in fact a phenomenon of very recent vintage. Words to characterize wine’s components have surely existed as long as grape juice has been fermented, but the publication and popularization of lists of wine vocabulary is a baby-boomer invention, a post-1960s artifact. And a peculiarly Anglo-American one. It was in the 1960s and early 1970s that tasting groups and wine education courses arose in the U.S., making wine tasting events and especially blind tastings (as opposed to wine consumed at the dinner table with food) more and more popular. In these forums, a standard terminology was needed, heralding the arrival of the wine glossary or lexicon.

What would seem to be a neat assemblage of terms turns out to vary widely over time and from writer to writer. Describing sensory perception is bound to be idiosyncratic but it also betrays patterns of bias and embedded cultural assumptions and desires. English professor Sean Shesgreen has called wine reviews, like cookbooks, an instance of the pastoral: “a literary genre inventing idealized, imaginary, and nonsensical images of country life for the amusement of city dwellers.” The words we use to describe wine are necessarily metaphoric or associative, and these connections often point to what we want from wine—what degree of social status, sensual indulgence, or salutary benefits we expect it to confer.

It was in the early 1960s, in the context of the “wine appreciation course,” that British wine authority Michael Broadbent developed one of the first glossaries of wine terminology. At the time, he could find no list of wine tasting terms for the non-professional published in English. The content of this lexicon, published in book form in 1968, betrays the conservative stance of the British wine establishment focused on wine as a signifier of class. As the wine director of Christie’s, Broadbent has had access to extremely rare and old wines, and his view of what wine does is clear when he notes in his introduction that wine lovers “always appear to be the most civilized of men.” Wine implies cultivated taste and cultivated taste implies knowledge of wine, therefore the beverage itself is best assessed in terms of its “nobility” or “lack of refinement.” Wines, like those who drink them, must display “good breeding,” “elegance,” and “distinction.” Unpalatable wines are “coarse,” “rough,” and “vulgar.”

This way of attributing class characteristics to wine was hardly unique to Broadbent. As Hugh Johnson notes in his memoir, A Life Uncorked, wine writing used to rely heavily on similes and metaphors that were highly anthropomorphic, giving wines human traits, particularly feminine ones: “Wines turned up as pretty little girls, in the full bloom of womanhood, broad-hipped, matronly, benign in maturity or growing frail with age.” Johnson, bemoaning a turn to more formulaic wine writing, is nostalgic for this golden age—a time when wine language was less codified, more expressive (and clearly less politically correct), but also restricted to a coterie of initiates whose taste and descriptive powers were beyond reproach.

In 1976, Maynard Amerine, the eminent UC Davis professor of viticulture and enology, codified his own version of a lexicon in his book Wines: Their Sensory Evaluation. His approach entirely opposed Broadbent’s; he wanted to put the sensory evaluation of wines on a more objective footing and openly rejected the kind of judgmental terminology that Broadbent had relied upon. Amerine’s glossary of wine terms focused on identifying flaws in wine, on words that had definite chemical meanings like “acetic” and “sulfur dioxide,” and on those that are universally recognizable, like “bitter” or “astringent.” Amerine actually makes a “plea for less fanciful terms than those so often found in the popular press” and offers a kind of anti-glossary—a list of terms that are to be used with caution or not at all, because they are flimsy, meaningless, or simply ridiculous. Among the terms he rejected were “elegant,” “feminine,” and “superficial.”

It is Robert Parker who, as the most influential American wine critic, has had the most singular impact on contemporary wine parlance. His influence soared in the 1980s, and his is a boomer vocabulary par excellence—casting himself in the role of anti-establishment crusader, appealing to pseudo-objectivity by way of point ratings, and larding his reviews with words that connote indulgence. The glossary of wine terms published on his website, for instance, includes many terms that stress the sensual experience of wine: “decadent,” “lush,” “aggressive,” “brawny,” “fleshy,” and “mouth-filling.” As his biographer, Elin McCoy, put it, “he practically had a patent on the adjective ‘hedonistic,’ at least as a wine term.”

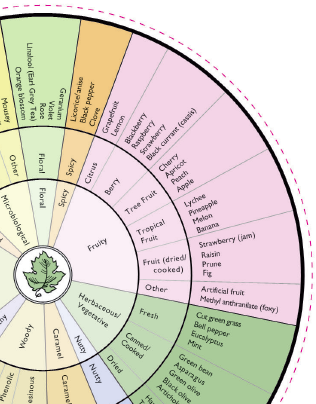

Parker wanted to democratize wine criticism, and UC Davis wanted to standardize its evaluation (most evident in Ann Noble’s Aroma Wheel, which organizes aromas into categories of fruits, floral tones, and so forth), and the combination of these approaches has culminated in a contemporary discourse about wine that can often read like a grocery list, a cornucopia of fruits and vegetables. The value of these terms is that they are familiar and recognizable as points of comparison, but a review composed this way—“cascades of potent plum, cherry, and blackberry fruit swirling around wafts of black pepper, bay leaf, and exotic spice, which lasts and lasts on the finish, hinting at smoky, meaty notes”—reads like a particularly unappetizing meal in a blender. But fruits are benign and seem to put wine in the category of things that are healthful and good for you, with all the heart-healthy and anti-oxidant properties they imply.

We are now clearly in a post-Parker era; if we now have websites that base recommendations on one’s individual preferences a la Netflix or Pandora, his relentlessly analog brand of authority can no longer hold the same sway. Blogs like alicefeiring.com or drvino.com go beyond tasting notes to delve into the politics of wine production and whole new classificatory schema arise, based not on a point scale of sensory fulfillment but on wine’s carbon footprint and the merits of organic, biodynamic, or dry-farmed grapes. At the current moment, wine is implicated less in a discourse of class or of taste, but one of environmental ethics and a debate about what constitutes “natural.”

It’s hard to talk about wine. Our vocabularies of taste and smell are woefully deficient. As the conceptual artist Sissel Tolaas (whose aromatic installation is included in How Wine Became Modern) is wont to say, we suffer from a kind of “olfactory blindness.” Yet in compensating for this lack, we project a host of meanings—signifiers of status, fulfillment, purity—onto what is, in the end, just a drink—albeit a very tasty one.

Erin Hyman is an editorial associate at SFMOMA, and worked previously as a researcher helping develop the exhibition How Wine Became Modern. Her interest in language dates back to her previous life as a lit professor, when she did a lot of thinking about words and what they reveal.

Comments (2)

Bravo! A wonderful article.

Thanks for this fantastic essay! I particularly appreciate — albeit with a melancholy smile — your connecting the dots between the rarefied fine art world and that of wine appreciation/criticism. I will cross post this next week, for sure.