FYI: The Revolution Has Just Been Tweeted

Twitter began as a revolutionary social networking tool for the over-caffeinated, but now it can genuinely claim to have started a real revolution. Over the weekend numerous accounts have emerged detailing how the text-based microblogging service allowed Egyptian protesters to connect with one another and organize. Their goal was ambitious by any standard: to challenge a 30-year-old dictatorship by orchestrating massive nonviolent demonstrations. It also must have been quite a shock to Americans who are constantly bombarded with images of Muslims as suicide-bombing, bloodthirsty terrorists. Yet there they were — hundreds of thousands of them — risking their lives and the lives of their families in nonviolent protest against an anti-democratic regime. They were tired of martial law, of having their poets arrested, of having journalists routinely jailed and beaten, of enduring crushing poverty, and ultimately of having no say in their own destinies. Indeed, contrary to American media stereotypes, ordinary Egyptians were carrying out what appeared to be as dignified and as civilized a show of solidarity as one could hope to see anywhere in the world. All we could do was watch from the comfort of our living rooms.

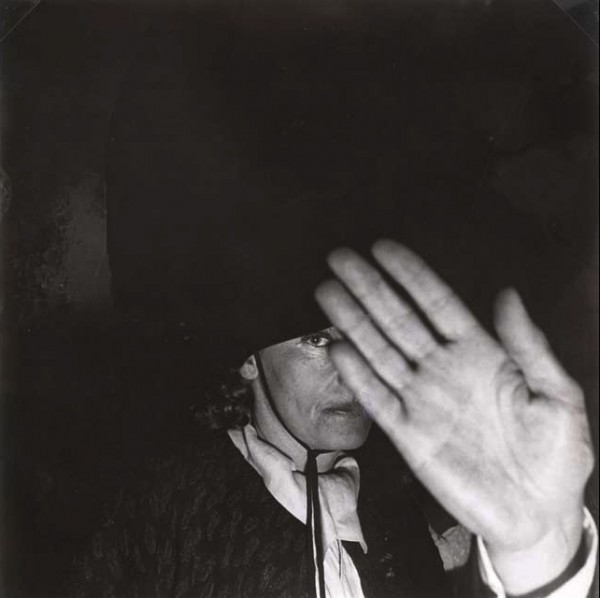

However, this Twitter-driven revolution is all the more fascinating to watch when thought of in the context of the SFMOMA show Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera. It’s interesting because the show examines how social media (photography & film were the original social media) have evolved along voyeuristic and dystopic paths. We now live in an era where one hand gives the promise of greater intimacy while the other hand takes away a user’s privacy. Today’s technology blurs the ideas of what public and private are. More ominously, it also blurs our sense of what is real. Not so long ago people used to be paranoid about having cameras everywhere, and they still are — but that paranoia was rooted in a one-way camera and a one-way television signal. But now that media devices are ubiquitous and interactive — cell phones, flip cameras, iPads, the web, etc. — anyone can be a reporter and anyone can be a witness. So maybe now we think we can watch the watchers that are watching us? It’s not just the unseen authorities that are watching now, it’s everyone, or at least that’s what they want us to think. So are we better off, or are we not? It’s a question worth asking.

Of course Gil Scott-Heron’s famous spoken-word poem, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” makes the point that revolution is not necessarily literal, but something that is psychological, as well. It’s important not to miss his key point, though: that you “need to get in synch with everyone to understand what’s going on.” It’s quite a conceptual leap for those fixated on their own situation, unaware of what is going on outside their own network. Or for people who are addicted to Fox News or talk radio, or even, dare I say, NPR. But new tools like Twitter and Facebook have brought political dissent into a completely new realm. More so if you happen to live outside of Europe and the United States, where social media are a lifeline.

Yesterday the Independent reported about one protest organizer, a woman named Mona Seif:

When Egypt cut the internet last week, she was one of 20 activists who took their laptops to a private house and started the “Twitter Centre of the Revolution,” getting messages to the outside world, thanks to one of their number being connected to an ISP which Egypt did not initially shut down because it almost exclusively serves financial services. “I use Facebook and I have a blog, but Twitter is my favourite tool for political issues,” she says.

Seif is a post-graduate student in cancer biology at Cairo University, (where) she is one of the leading figures who used blogs and Twitter to help spread the call for the first protest on 25 January. Protest runs in her family: her father is a well-known human rights lawyer, Ahmed Seif el-Islam, who was serving in a Mubarak jail when she was born and is among more than 20 lawyers who have been arrested.

It is sadly ironic that those who understand the power of images the most are not artists, but often politically oppressive forces. Last week the Mubarak government understood it when they instituted a blackout as it pulled the plug on the internet and then hunted down journalists with armed gangs. The last thing they wanted was to have pictures of themselves shooting protesters. Or running them over in cars. Or randomly beating people. Or kidnapping them. But even they could not get away from all the cell phones and cameras in the hands of ordinary people. People who were risking their own lives to record and publish what was happening. While the journalists were in hiding, it’s the people tweeting from balconies and doorways that made this revolution happen.

Comments (2)

On your 2/1 post commenter N. Fellah made a point about the power of technology today…

LOVE THIS REVOLUTION ! ! ! WILL LOVE IT MORE MORE MORE AND WITH OR WITHOUT ME AND MYSELF.