Sequent Occupancy: A brief history of the SFMOMA site for the past 900 years (Part 2)

I don’t drink coffee, so let’s have a beer … My posts are always collaborations and are presented in two parts. Part 1 is a summary of a shared experience with my collaborator(s). Part 2 is a response, often in the form of a project created specifically for this blog.

After meeting my collaborator, Joshua Singer, at The Trappist a few weeks ago, we created a post about the primary topic of our beer-induced evening: sequent occupancy, which is the study of the history and influence of human occupancy of a specific region over intervals of historic time. For the past few weeks we’ve been sharing information about the history of the current SFMOMA site.

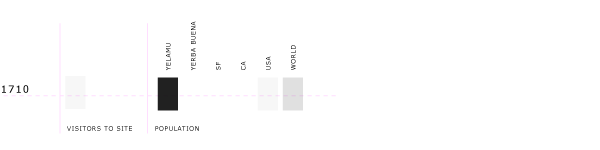

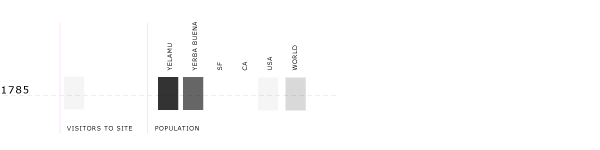

Below is our very selective and slippery and most definitely epic history of the current SFMOMA site for the past 900 years, based on population shifts as they influenced development of the site. The images and texts are compiled from a variety of sources ranging from the Folsom Street Fair website to Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City.

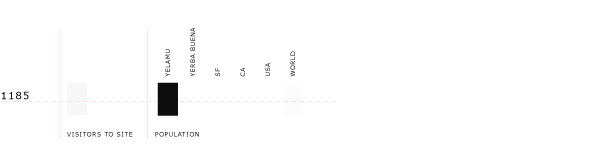

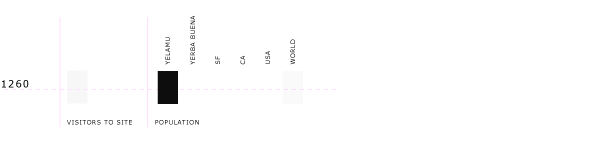

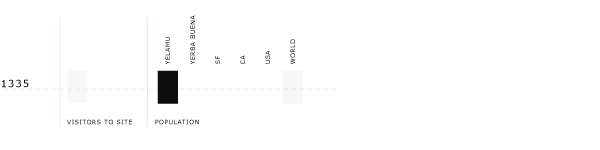

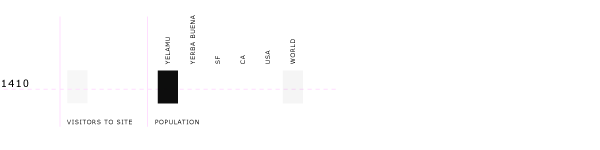

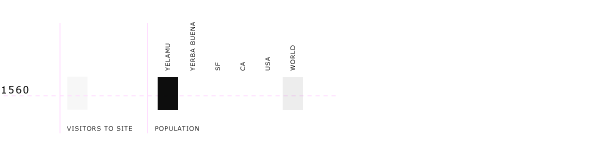

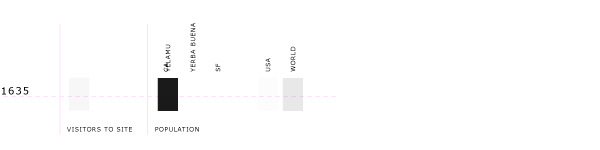

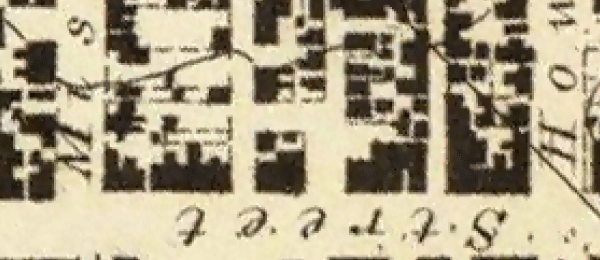

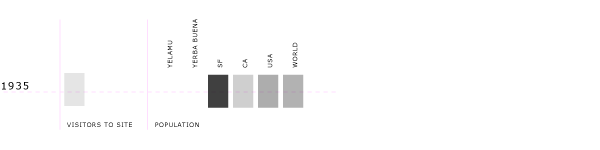

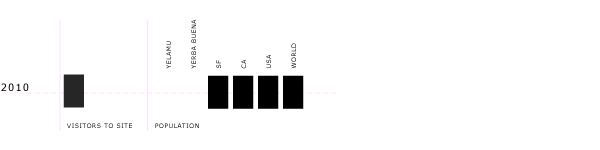

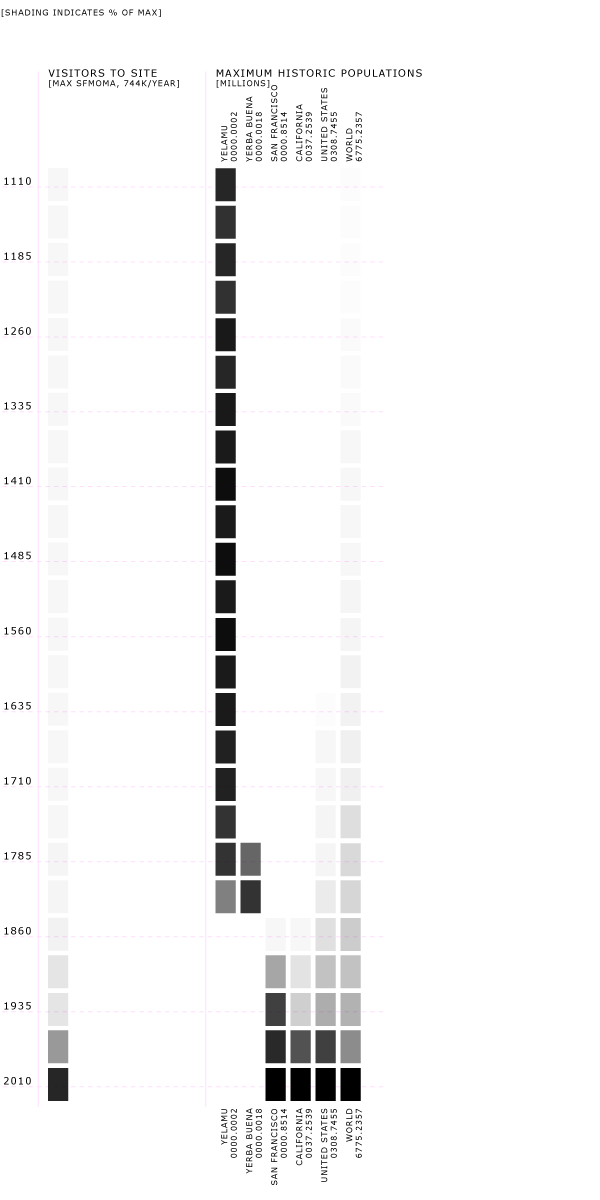

The rectangles and dates show the calculated/estimated populations for each of the categories (the world, California, SF, SFMOMA attendance, Yelamu …), and represented percentages of population shifts with the tints. The black rectangles represent 100%, or the highest population count on record in each category. The lighter the rectangle, the lower the percentage of population in that category. The rectangles don’t correspond to each other in a horizontal manner, but rather in a vertical relationship to all the other dots in that category. Example – The Yelamu had the highest population before the Spanish came, and then the population fades. SFMOMA has the highest attendance rate today, so the rectangles start out gray and get darker until the last graphic when it is black. At the bottom of our post there is a graphic of the entire timeline so you can easily track the population shifts in one glance.

[Referent site for possible precolonial geography of current SFMOMA at 151 3rd St., Google Earth, “38° 5’20.72″N, 122°57’34.30″W]

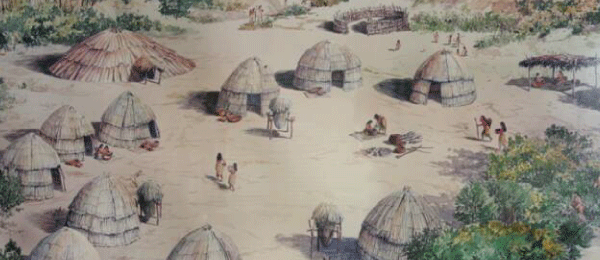

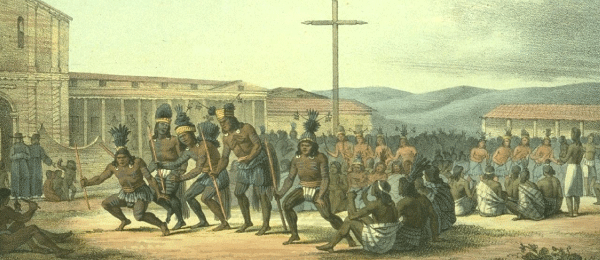

The indigenous inhabitants of San Francisco used more than 150 different plant species in addition to dozens of animal species to provide for their needs. (Bocek 1984) Thoughtful management by the Yelamu* (* The descendants of the indigenous people of the Bay Area call themselves Ohlone, and their preference should be paramount. Following the careful scholarship of Randall Milliken, I use Yelamu here to refer to the approximately 160 people who inhabited several villages in the area now known as San Francisco. [Milliken 1995] They shared many close linguistic and cultural affinities with other indigenous peoples around San Francisco Bay, the Santa Cruz peninsula, and Monterey Bay. I use the term Ohlone when referring to this larger cultural and linguistic group. They helped foster the abundant and diverse native plant communities on which they depended. Willows, for example, needed pruning to encourage the straight young poles preferred by basketweavers. [Cultural Contact at the Presidio, by Pete Holloran]

The Yelamu were a tribe of Native Americans of Northern California in the Ohlone (Costanoan) language group. The Yelamu lived on the northern tip of the San Francisco peninsula in the region comprising the City and County of San Francisco before the arrival of Spanish missionaries in 1769.

On the fifteenth of December 1774, Viceroy Bucareli sent from Mexico City a very important letter to Father Junipero Serra at Monterey. “In consideration,” he wrote, “that the port of San Francisco, when occupied, might serve as a base of subsequent projects, I have resolved that the founding of a fort shall take place by assigning twenty-eight men under a lieutenant and a sergeant. As soon as they are in possession of the territory, they will be sure proof of the king’s dominion. For this purpose Captain Juan Bautista de Anza will take a second expedition overland to Monterey from Sonora [Mexico], where he must recruit the said troops. He will see that they take their wives and children along so that they may become attached to their domicile. He will also bring along sufficient supplies of grain and flour, besides cattle. … When the territory has been examined, and the presidio is established, it will be necessary to erect the proposed missions in its immediate vicinity.” This was the first move in the grand project of founding San Francisco. (“The Founding of San Francisco,” The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco)

[The Padron – mounted horseman]

The Jesuit missions established in Lower California, at Loreto and other places, were followed by Franciscan missions in Alta California, with presidios for the soldiers; adjacent pueblos, or towns; and the granting of large tracts of land to settlers. By 1782 there were nine flourishing missions in Alta California — San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Carlos, San Antonio, San Luis Obispo, San Buenaventura, San Gabriel, San Juan, and San Diego. Governor Fajés added Santa Barbara and Purissima, and by 1790 there were more than 7,000 Indian converts in the various missions. By 1800 about forty Franciscan fathers were at work in Alta California, six of whom had been among the pioneers of twenty and twenty-five years before, and they had established seven new missions — San José, San Miguel, Soledad, San Fernando, Santa Cruz, San Juan Bautista, and San Luis Rey. (“Ranch and Mission Days in Alta California,” by Guadalupe Vallejo, The Century Magazine, December 1890)

“On June 27 we reached the vicinity of the port and pitched camp, which was composed of 15 tents, on the bank of a large lagoon which empties its waters into the arm of the sea or the port that extends inland 15 leagues to the southeast. The object was to wait for the ship to mark out the site for the presidio near a favorable anchorage. No sooner had the expedition gone into camp than many pagan Indians appeared in a friendly manner and with expressions of joy at our coming. Their satisfaction increased when they experienced the kindness with which we treated them and when they received the little trinkets we would give them in order to attract them, such as beads and estables. They would repeat their visits and bring little things in keeping with their poverty, such as shellfish and wild seeds.” (Francisco Palou from “Deep California: Images and Ironies of Cross and Sword on El Camino Real,” by Craig Chalquist)

[Danse des Californiens at San Francisco, from a drawing ca. 1815].

He therefore organized a series of centers in good agricultural lands, around which he gathered the reluctant and lazy savages. At these centers the buildings that are known to us as the missions were built. The original missions were not only churches, but also a group of buildings serving for workshops, granaries, and dwellings. (“Missions of Spanish Era Had Wide Influence,” by F. Gordon O’Neill, editor, Catholic Monitor.)

[View of San Francisco, California, formerly Yerba Buena in 1846–47.]

From its very beginnings, San Francisco was unlike any other American city: the absence of established social conventions, the mad quest for gold, and a heterogeneous population coming from all parts of the globe, all contributed to a varied and lively urban scene unencumbered by social restraint. Starting in 1849 Mexicans, Chileans, French, Anglos, Germans, Chinese, Indians, and countless others converged on the Peninsula in search of instant wealth. (“William Richardson and Yerba Buena Origins,” FoundSF.com)

[An image of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (or one of his brothers?) who helped transition California from a Mexican district to an American state. In 1850 California becomes a state.]

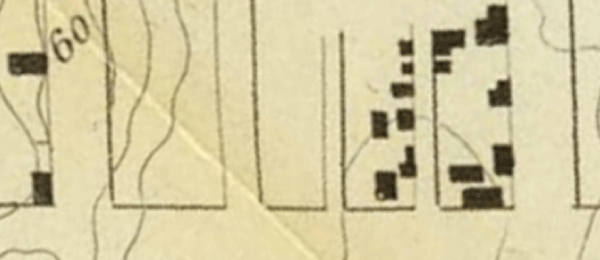

[U.S. Coast Survey Map, at 151 3rd St.]

June 11, 1856, the City and County of San Francisco was formed, and a new county called “San Mateo” was created out of the remainder of the old County of San Francisco. [1856 near the current SFMOMA location] Peter Donahue, at First and Mission, has his brass and irons works, and laid the foundation for the Union Iron Works. With James and Michael Donahue, in 1849, Peter had established the first iron foundry in California. It was also there that the gas works were located. A little farther on, and between First and Third, Folsom and Bryant streets, was “Pleasant Valley.” (San Francisco News Letter, September 1925)

[U.S. Coast Survey Map, at 151 3rd St.]

At precisely fifteen minutes to 1 p.m. Oct. 8th, 1865, the City of San Francisco was visited by the heaviest Shocks ever felt in the vicinity by “the oldest Inhabitants.” Scarcely a house in the city that does not show some mark of the visitation, in cracked walls, open joints, flaked plaster, or a cranky position and many of the old heavy brick structures are so shaken up and twisted as to be dangerous to the occupants. On Tehama, Howard, and Mission streets, the ground has become slightly undulating, where it was perfectly level. (“General Effects of the Shake,” The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco)

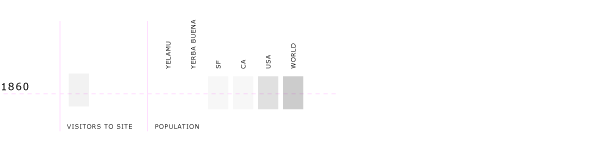

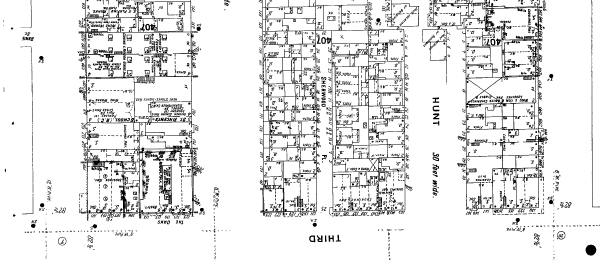

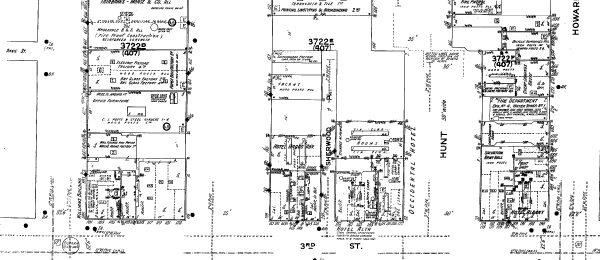

[151 3rd St., Sanborn Map collection]

In 1900 one out of every five people in San Francisco lived between Market and Townsend streets, from the waterfront to Eleventh Street. (“An ‘Unvanished’ Story: 5500 Years of History in the Vicinity of Seventh & Market Streets, San Francisco, CA,” a report by the Southeast Archeological Center, National Parks Service.)

“With money San Francisco can reduce its death-rate by improved sanitation; it could possess its own public utilities, as water and artificial light, and save us the moral humiliation of perennial corruption, which dims our civic pride and embitters our political life … Then would follow museums, galleries of art, and theaters, until San Francisco, by reason of its remarkable meteorological advantages, would assume the position of the most beautiful city in America, and its population the most artistic and pleasure-loving, drawing to its realm myriads of strangers from year to year.” (Mayor James D. Phelan, San Francisco News Letter, Christmas Number, 1897)

[Third Street looking towards Mission and Market.]

On Wednesday, April 18, 1906, an earthquake devastates San Francisco. The neighborhood SFMOMA is currently in was known then as “South of the Slot.”

[Mission St. between 2nd [Second] & 3rd [Third] Sts.]

Old San Francisco, which is the San Francisco of only the other day, the day before the Earthquake, was divided midway by the Slot. The Slot was an iron crack that ran along the center of Market street, and from the Slot arose the burr of the ceaseless, endless cable that was hitched at will to the cars it dragged up and down. In truth, there were two slots, but in the quick grammar of the West time was saved by calling them, and much more that they stood for, “The Slot.” North of the Slot were the theaters, hotels, and shopping district, the banks and the staid, respectable business houses. South of the Slot were the factories, slums, laundries, machine-shops, boiler works, and the abodes of the working class. (Jack London, “South of the Slot,” Saturday Evening Post, May 1909)

[151 3rd St., Sanborn Map collection]

(First SFMOMA site noted, but not part of our site study.) SFMOMA was founded in 1935 under director Grace L. McCann Morley as the San Francisco Museum of Art. For its first sixty years, the museum occupied the fourth floor of the War Memorial Veterans Building on Van Ness Avenue in the Civic Center. A gift of 36 artworks from Albert M. Bender, including The Flower Carrier (1935) by Diego Rivera, established the basis of the permanent collection. Bender donated more than 1,100 objects to SFMOMA during his lifetime and endowed the museum’s first purchase fund. (Wikipedia)

[Hotels and misc. businesses at 151 3rd St., 1946, Google Earth Historical]

The next swing of the wrecking ball was to be in the area of South of Market from 3rd to 6th streets and between Mission and Folsom. First publicly marketed as the “Prosperity Plan” by Ben Swig and his realtor backers, it hoped to build a downtown stadium in the area, and bring in the highway access, parking lots, and super shopping malls to complement this kind of auto-directed urban playground. Interestingly, under existing federal and state guidelines of “blight,” the area did not qualify, despite Swig’s efforts to alter boundaries and manipulate definitions to bring reality into line with his vision. Tellingly for what would occur later, this initial attempt was foiled by a spontaneous coalition of small business owners who successfully resisted this effort to devalue their property and ruin their livelihoods by ignoring the residential/small commercial mix that had typified the neighborhood from its beginnings. The area was de-designated in 1958. (Folsom Street Fair website)

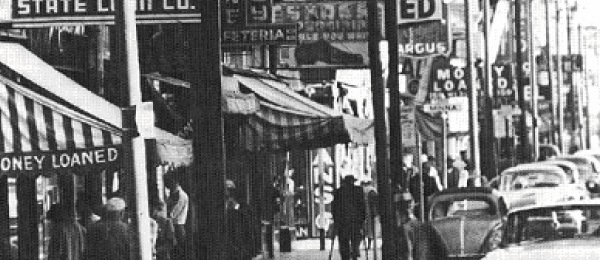

In 1960 South of the Slot was a collection of “residential hotels, pawn shops, small shots and manufacturing, diners and taverns.” On SFMOMA’s block were the following businesses: Rochester Clothing for Men, Union Liquor Store, Zenith Club Tavern, Mac’s Loan Co., Square Deal Jewelers, Carmel Barbershop, Max’s Shop for Men, and the Colorado Hotel and Hotel Carmel. (text from Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City, “The Lost World: South of Market, 1960, Before Redevelopment,” map and text)

The U.S. Congress established the Federal Poverty Program, which was in intention an alternative mechanism for resolving problems occurring in urban areas filled with lower-class and poor individuals and families. By the end of 1964, four Anti-Poverty Target Areas had been established in San Francisco, under the aegis of the Economic Opportunity Council, all aligning along an assumption that peoples of color necessarily correlate with poverty — Western Addition, Hunter’s Point, Chinatown, and the Mission. A powerful, subversive potential to use the Poverty Program to combat the Redevelopment Agency in San Francisco, and to free the Poverty Program from its latent racist underpinnings, was realized in June 1966, when a fifth Anti-Poverty Target Area was established, called Central City and covering the areas north and south of Market Street, known as the Tenderloin and SOMA. (Folsom Street Fair web site)

Yerba Buena Center officially designated an urban renewal area. In 1967 The Redevelopment Agency initiated demolition. The tenants of the area were beaten, driven out by arson, and forced to live in buildings that the city took over and turned into wrecks. But they were tenacious. It was a class war, a war to move the wealthy across the line that Market Street had been, into blue collar territory. (text from Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City, “The Lost World: South of Market, 1960, Before Redevelopment,” map and text.)

Various neighborhood organizations, including TOOR (Tenants and Owners in Opposition of Redevelopment), would fight redevelopment in SOMA for the next two decades, and their successors, like TODCO (Tenants and Owners Development Corporation), are still fighting for tenants’ rights today.

[Parking lots at 151 3rd St., 1987, Google Earth Historical]

[In 1991 Mayor Art] Agnos ended the nation’s longest stalled public works project at Yerba Buena to develop a cultural hub that includes the Museum of Modern Art, Yerba Buena Center, and Yerba Buena Gardens. (Wikipedia)

[SFMOMA moves from the Civic Center and opens in their new location at 151 3rd Street between Mission and Howard on January 18, 1995.] With its new building, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art doubled its space; it hopes to double its attendance. Early figures suggest that its hopes may come true. Between its Jan. 18 free public opening and Tuesday, 53,000 people experienced the Mario Botta–designed galleries — 10,000 on Jan. 18 and 8,000 during four hours on Family Day, Super Bowl Sunday. Yearly attendance at the old Civic Center museum was 240,000. According to SFMOMA spokeswoman Chelsea Brown, projected attendance for the first year in the new museum is 600,000, with numbers expected to even off to 500,000. Attendance on Tuesday, the first day of regular hours, was 2,300, well above projected average daily numbers. (“New SFMOMA Attendance Figures are Souring,” SFGate.com, Feb. 2, 1995 )

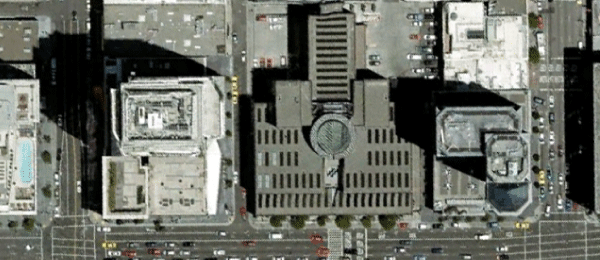

[151 3rd St., 2007, Google Earth]

[151 3rd St., 2007, Google Earth]

On May 10 [2009] the museum is to open its first new space since 1995 — a 14,400-square-foot rooftop sculpture garden, designed by the San Francisco firm Jensen Architects. On display will be large-scale works by Louise Bourgeois, Ellsworth Kelly, and Barnett Newman, among others. “It’s fully funded, fully endowed, on budget and on schedule, and that puts a smile on my face these days,” [Director Neal] Benezra said. “Outside of New York, there’s more great contemporary art in the Bay Area than anyplace else in the U.S., and we have to convince our donors that if they are good enough to leave their objects to us, there’s space to show them.” (“Taking a Step by Step approach to Growth,” New York Times, March 16, 2009)

By the end of the summer, 2011, SFMOMA will surpass 22 million visitors since 1935, with 50% visiting since the move to Third Street in 1995. (info from SFMOMA Visitor Services)

Upon completion of SFMOMA’s planned expansion [in 2016], works from the Fisher Collection will be on display in a new wing that will also incorporate art from the museum’s collection. In addition, works from the Fisher Collection will be interwoven with SFMOMA’s modern and contemporary holdings in existing galleries. Together, they will form one of the world’s most important collections of art of the past 50 years. In July 2010 the museum selected Norwegian architecture firm Snøhetta to design the expansion, which will triple the size of SFMOMA’s galleries. (SFMOMA press release, Sept. 25, 2009)

——–

The following shows the entire 900 years.

Comments (3)

Jen and “Abstract Art” – I know this was a huge post, so I want to thank you for taking the time to not only spent time with it, but comment as well. It means a lot. I’ll share your thoughts with my collaborator Josh Singer. He worked incredibly hard on this. My best to you both.

I’ve lived in SF for two years now and SFMOMA is one of my favorite places to visit. I’ve learned more about the history of SF in ten minutes than I have over the past two years. Thank you for the great article.

We moved to San Francisco a year ago, and I am always looking for thoughtful introductions to the history and geography of the city. This is a terrific piece, a detailed window into the story of San Francisco through a specific place. Thank you for your research and it’s great presentation here.