Collection Rotation: Tyler Green

Our regular feature, Collection Rotation. Every month or so I invite a someone to organize a mini-“exhibition” from our collection works online. Please welcome none other than TYLER GREEN to Open Space for this month’s iteration. Welcome, Tyler!

Carleton E. Watkins, San Francisco Bay. Golden Gate from Telegraph Hill, ca. 1884; albumen prints; 25 in. x 120 1/4 in. (63.5 cm x 305.44 cm); Collection of the Sack Photographic Trust and fractional gift of Paul Sack to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

For years SFMOMA’s paintings and sculpture collection galleries effectively began in 1906, with three Henri Matisse paintings: The famed Woman with a Hat and portraits of Michael and Sarah Stein. Like many San Franciscans, I grew up knowing the story of how the Steins built their collection in France during the heyday of the Parisian avant-garde, received word of the 1906 earthquake and fire via telegram, and how they rushed back to San Francisco to see what of their wealth remained. The opening of SFMOMA’s collection galleries was always a wonderful way of linking the city and its history to art history.

Recently, for The Anniversary Show, a team of SFMOMA curators presented a new, equally interesting “beginning” of SFMOMA’s collection. They started with the museum’s founding in 1934, particularly with a superb painting by Alfredo Ramos Martinez and works by Mexican modernists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. The impact of that wowsa gallery — combined with a new presentation of Mexican modernism at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art — could be extended if SFMOMA’s curators and donors work to improve the museum’s small collection of Mexican modernism.

Either version of those collection-opening galleries seemed to promise that SFMOMA was the modern museum of the West, a counterpoint to the Eastern-plus-Europe-centric Museum of Modern Art, New York. For whatever reason, SFMOMA has never quite prioritized the West the way those two galleries have suggested it might have. It’s always been a museo-fantasy of mine that it would, or will, that SFMOMA would collect and present art of the modern era from a distinctly Western point of view, from a point of view that argues that the West has an art-historical story to tell and that the West need not merely mimic the East in its presentation of modern and contemporary art. If the West’s largest museum of modern and contemporary art doesn’t champion the West as a driver of art history the way MoMA champions New York, who will?

Given the opportunity to have a little fantastical fun with SFMOMA’s collection, I thought I’d show how SFMOMA could assert itself by asserting its Westernhood. Inspired by last year’s two-building permanent collection installation at Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art, I’m going to mix photography with painting and sculpture. (And there are lots of ways that SFMOMA could “be” the West, this is just one wacky way of doing it. This installation could include dozens more works, and I encourage readers to make suggestions in the comments!):

My “exhibition” starts with a third option, inspired by a recent SFMOMA show. In 2008 SFMOMA curator Corey Keller’s thrilling exhibition Brought to Light effectively suggested a third “opening date” for museums of modern art, and photography-rich SFMOMA in particular: the 1840s, photography’s first decade. As coincidence has it, that’s the decade in which gold was discovered in the Sierra foothills and thus the decade in which modern California began. So I’ll start my collection installation with a photograph by America’s first all-American artist, Carleton Watkins: San Francisco Bay, Golden Gate from Telegraph Hill (ca. 1884, detail at top, panorama below).

Carleton E. Watkins, San Francisco Bay. Golden Gate from Telegraph Hill, ca. 1884; Collection of the Sack Photographic Trust and fractional gift of Paul Sack to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

(SFMOMA has nearly 30 Watkinses and organized a major Watkins exhibition, The Art of Perception, in 1999.) I’d include at least three more Watkinses here: The Domes from Eagle Point Trail, Yosemite (above); Donner Lake from the Summit; and Grizzly Giant (above). I’d also feature Eadweard Muybridge’s Panorama of San Francisco from California Street Hill (1878), followed by the museum’s Mahomet, from the series The Horse in Motion, one of Muybridge’s pioneering “animal locomotion” studies.

Eadweard Muybridge, Panorama of San Francisco from California Street Hill, 1877; panorama of eleven albumen prints from glass negatives with album; Collection of the Sack Photographic Trust

Because this is a digital, fantasy “installation” and because I’m making up stuff that doesn’t exist, I’d have the opening gallery of Watkins and Muybridge lead to two sets of galleries: One of artists who made art “following” Watkins’s landscapes, and another of artists making work in the tradition of Muybridge’s motion studies.

The first Team Muybridge gallery (t-shirts for the gift shop just waiting to happen!) would feature Sol LeWitt’s Muybridge II, and San Francisco-based Jim Campbell’s Digital Watch. SFMOMA doesn’t own any of Campbell’s “low resolution works,” but they’d be a nice fit here. (Campbell may be the living artist who most mines Muybridge.)

The next gallery would nod to Muybridge’s groundbreaking panorama pictures with Marco Brambilla’s Cyclorama (above) and Lucas Samaras’s Panorama. SFMOMA’s library has a complete set of Ed Ruscha’s early artist’s books, including Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations and Every Building on the Sunset Strip, and as they’re locomotion studies for the postwar automotive generation, I’d include them here, too.

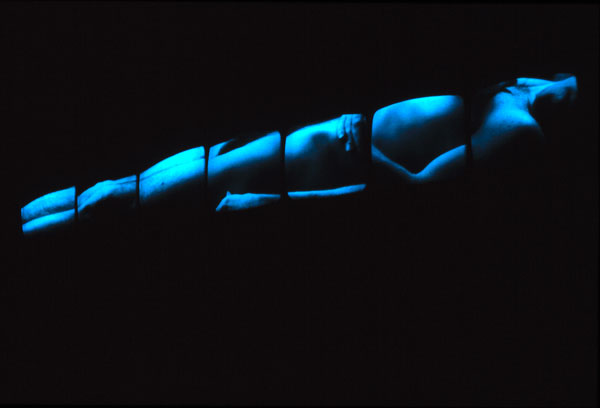

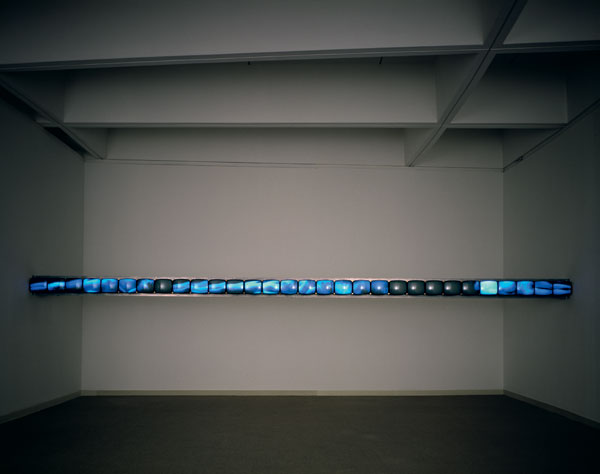

Next up: A gallery of “time-based works” that would include Gary Hill’s Suspension of Disbelief (for Marine), Bruce Nauman’s Stamping in the Studio, Dan Graham’s Opposing Mirrors and Video Monitors on Time Delay, and an early Bruce Conner, such as Breakaway (1966). Three of the four artists are based in the West, and Graham has made much work about the West.

On to photographers, including John Divola, a California-based photographer who has several works in SFMOMA’s collection and has made many, many works that seem to take Muybridge’s ”animal locomotion” as a point of departure, none more than his series Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert, a series Divola made between 1996 and 2001 which would have to be one of those things a curator includes in the hope that a museum trustee or donor sees it, likes it in the context in which it’s presented, and buys it for the museum [that is, we don’t have one—Ed.]. To make his series, Divola did what Muybridge did: he used a gizmo specially made for this kind of task, in this case a motorized 35mm camera.

I’d close the Team Muybridge section with Ed Ruscha’s Parts Per Trillion, a painterly riff on motion, distance, perspective. It’s also part of a semi-series of paintings Ruscha made in 1987 that play a John Baldessari–like game, only with words not images. When you see three tall-masted ships and “blank boxes” where words might go, what three names do you give those ships? (Me: Nina, Pinta, Santa Maria.)

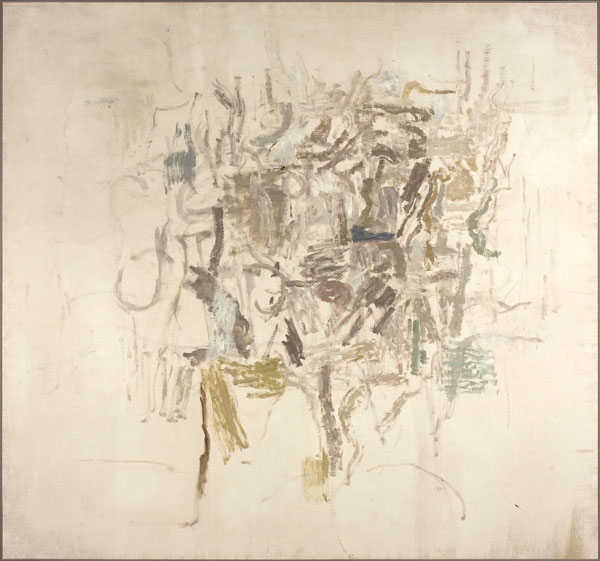

The Team Watkins galleries would start by showing how painters have addressed the monumentality and expansiveness of Western landscapes. (Once Watkins showed us the drama of the West with such compositional skill, painters had to find something new, something other than the kind of Grand View that was in favor in American landscape painting at the time.) My Team Watkins gallery or galleries would especially include works by artists who spent significant time in the West and would include: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Black Place I (below), Jackson Pollock’s Guardians of the Secret (which is likely based on a Tintoretto martyr painting but which is informed by Native American mythology), Mark Rothko’s sublime No. 14, 1960 and Untitled, 1960 (below), and Philip Guston’s White Painting I (below) and For M. This would also be a good place to install the museum’s Richard Diebenkorn Ocean Park paintings, the apex of American abstract painting.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Place I, 1944; Collection SFMOMA; © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1960; Collection SFMOMA; © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The next paintings gallery would feature a long-neglected San Francisco non-favorite: Gottardo Piazzoni’s The Sea and The Land murals. SFMOMA is almost the only art museum in town that hasn’t been involved in the Piazzoni murals story over the years, so my installation would, er, remedy that by borrowing them from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the city of San Francisco, which has loaned its “half” of the murals to the state treasurer’s office.

The Piazzoni murals have long been a forgotten landmark of San Francisco-based art.

Gottardo Piazzoni (1872–1945) The Land, ca. 1929–32. Oil on canvas, five panels, 12 x 6 2/3 ft. each. Transfer from the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Asian Art Museum through The Joint Committee to Site the Piazzoni Murals, 1999.196.2a-e

Gottardo Piazzoni (1872–1945), The Sea, ca. 1929–32. Oil on canvas, five panels, 12 x 6 2/3 ft. each. Transfer from the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Asian Art Museum through The Joint Committee to Site the Piazzoni Murals, 1999.196.1a-e

When they were made in 1931–32, they were a very big deal, indeed, so big that Ansel Adams photographed Piazzoni in his studio as he worked. Within a couple decades they were all but forgotten, perhaps because they weren’t particularly avant-garde. Then again, they weren’t exactly traditional, either, and they never really fit within any particular tradition. Perhaps worst of all, they were particularly Californian at a time when regionalist art was on its way out.

The Piazzoni murals should be art historically rehabilitated. In an unguarded moment, the famously compliments-shy painter Clyfford Still let slip to legendary curator Walter Hopps that he was a big fan of the Piazzoni murals, that they had meant a lot to him as his art took a turn toward the abstract. (Looking at five at once, you can kind of see why …) One of SFMOMA’s greatest, most important collections is its trove of Clyfford Still paintings. A selection of them — say 1947-H-No. 3; 1956-D; Untitled, 1951–52; Untitled, 1957 (below); and Untitled, 1974 — would follow the Piazzoni gallery.

Somewhere around here the Team Watkins and Team Muybridge galleries would come back together to feature artists whose work owes a debt to both photographers. SFMOMA has two Thiebaud landscapes. One, Sunset Streets (below), is a fictional urban landscape plainly inspired by San Francisco’s hilly streets. Go back to our first gallery, where we featured Muybridge’s panorama of the city. In your mind’s eye, flatten one of the streets up against the picture plane … and yeah, you can begin to wonder if Thiebaud looked at Muybridge’s (and Watkins’s) photographs of San Francisco.

Wayne Thiebaud, Sunset Streets, 1985; Collection SFMOMA; © Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA, New York

SFMOMA’s super Thiebaud riverscape, Flatland River, leaves the viewer floating in the air with a landscape down below. It reminds me of Watkins’s (and Muybridge’s) viewpoints of Yosemite Valley or along the Columbia River.

Wayne Thiebaud, Flatland River, 1997; Collection SFMOMA; © Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA, New York

Another gallery would include photographers who were (and are) Thiebaud’s contemporaries and their pictures of the land, especially Robert Adams’s expressway pictures, Joe Deal’s Colton, Calif., and Lewis Baltz’s Night Construction, US 50 East of Carson City (which also owes a lot to Watkins and Muybridge contemporary Timothy O’Sullivan). I always chuckle at Wessel’s San Francisco, California (1972) (below), which I like to think of as a dry, wry rhyme on Watkins’s famed photograph Agassiz Column and Yosemite Falls from Union Point (1878–81).

My installation started with a Watkins picture of the Golden Gate. I’d finish it with Richard Diebenkorn’s Berkeley #23. Just before Diebenkorn began his Berkeley paintings, he built himself a studio in the backyard of his Berkeley home. Diebenkorn hotly denied that there was a relationship between landscape and his Berkeley abstractions, but, well, it’s hard not to read landscape into them. That old-goldish color at the top of the painting makes me wonder if that’s the color Diebenkorn saw coming off of the Bay late in the day …

Richard Diebenkorn, Berkeley #23, 1955; oil on canvas; Collection SFMOMA; © Estate of Richard Diebenkorn

Tyler Green edits the Modern Art Notes blog, which is published by Artinfo. He is also the U.S. columnist for Modern Painters magazine. He has written for numerous newspapers and magazines.

Comments (3)

OH that is Prop. 65 – rather

materials that cause cancer !

Interesting. Just discovered your blog !

One condition you may not know about the C. Still works is that they are required to remanin as they are – all together in perpetuity.

PS-

You may also enjoy some trivia-

On the 4th floor on the north side of the Museum a wall cover the ‘thrown’ lead sculpture by Richard Serra – off limits to the public due to Prop 35 CA laws….

Great post, the collection rotation series is the best part of this blog. I always discover new works from the collection. Like that Wessel photo, so good.

I’d be curious to see who else you could bring in on it, either locally or abroad. Maybe more musicians or artists or filmmakers? The mayor? Curators from other major museums? So far the Tucker Nichols version has been the best, but really they’ve all been good. Scott Hewicker’s David Ireland tribute was also fantastic. Keep it up!