Harvard Bestows Hardware on Lord

I made a quick trip to Cambridge, MA yesterday to attend Harvard University’s award ceremony for Catherine Lord, recipient of the 2010 Harvard Arts Medal. Lord is one of the most original writers on art, archives and photographs of her generation – though I think she’s far less known than her exceptionally witty, insubordinate, and thoughtful writing earns her the right to be. Previous Harvard Arts Medal recipients include the likes of John Ashbery, composer John Adams, Mira Nair, John Updike, Jack Lemmon – big shots in their worlds, as is Catherine Lord, only she does it quietly – let’s say she’s an artist’s artist, an artist’s critic, a writer’s writer, an artist’s curator, etc..

How might you begin getting to know Lord’s work? She’s one click away on Amazon, but I’ll get back to that in a minute. I’d start with OCTOBER’s special issue devoted to Warhol, and Lord’s rethinking of the writer Valerie Solanas entitled “Wonder Waif Meets Super Neuter,” an essay that has also been delivered to delirious praise as an illustrated lecture. While you wait for that issue to appear, read the page-turner called The Summer of Her Baldness, A Cancer Improvisation, (U. Texas Press, 2004), an image-text narrative on the identity-subjectivity triathlon that was Lord’s experience of breast cancer, chemo baldness, and the supposedly healthy world’s apprehension of the sick, the lesbian, the bald lesbian, the bald sick lesbian, etc…. Earlier essays of Lord’s have appeared in numerous exhibition catalogues, anthologies of writing on photography, feminisim, queer studies – google will get you there. Upcoming publications include a long overdue Phaidon history called Art and Queer Culture 1885-2005, written with the art historian Richard Meyer, and a photo-text project inspired by and grounded in the archives of Lord’s childhood home, the island of Dominica, called The Effect of Tropical Light on White Men.

One of the great things about Lord’s bibliophilia and photophilia is how utterly unbiased she is toward any one type of speech, and thus how many odd – and queer – corners she leads us to. Right now she’s working on a photo project about book dedications, producing diptychs that show 1) a gorgeously reproduced book cover and 2) that book’s dedication. My current favorite dedication from this series is this one: “For Simone de Beauvoir, who endured.”

Here in an excerpt from a recent text of Lord’s on this subject:

To dedicate a book is to hide the private in public view. It is to multiply a solitary decision, to commit to an act that can be lonely or playful or mischievous. A dedication is a speech act.. Just like saying, “I do thee wed,” is to cause to come into being a marriage, to put into print the sentiment, “I give to you the words I have written,” is make the gift of the words about to be read, to tender, in advance, the object that the reader holds in her, or his, hands. It is to return from around the corner upon the support that makes possible language itself. To cause a fluid to bleed upon unmarked flesh is to accept a position in a field of generosity.

The act of dedication occupies that uncharted time and uncertain space between thoughts disciplined into words and the binding together of those thoughts upon paper. The gift is not made until the object is brought into existence by giving it a spine. To dedicate is to enlarge the social body in which artists function, to amplify the fertile ground between public and private. The gift is perverse. The giver does not relinquish what she has given. Even if she wished to do so, she cannot. Instead, the gift binds its giver to the recipient.

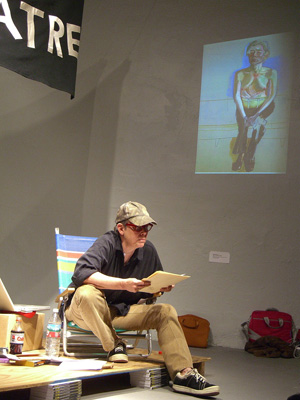

It was Lord’s reading of this text that brought the assembled students, faculty, friends, well wishers, and admirers to the edge of their folding chairs in room 203 of Harvard’s New College Theatre on Thursday night, April 29. The previous hour had been spent listening to actor John Lithgow explain the reinvigorated role for the arts at Harvard, introduce Catherine Lord, and then listening to Lord’s witty, intelligent answers to Lithgow’s sometimes ham-fisted, but mostly well-intentioned questions. (“But Catherine, wouldn’t you agree that you do, well, try to be PROVOCATIVE sometimes?”) High on the wainscotted wall behind the two Ls, Catherine L’s slides of the dedications were shown, along with marvelous images from the c0mpletely perverse archives of The Effect of Tropical Light on White Men. The actual medaling part of the event came at the end of the ceremony, when Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust gave a well-written, thoughtful summary of Lord’s work and contributions to the arts, and then “bestowed the hardware,” as Lord herself put it. I felt the medal. It’s heavy.

p.s. Lord has been a professor in the Studio Art Department at UC Irvine since 1990, and was Dean of the Art School at CalArts from 1980-1990. She lives in Los Angeles.

p.p.s. The use of the noun “medal” as a verb, which I first noticed while watching the Olympic Games some 12 or so years ago, is still highly suspect.

Comments (1)

Thank you so much for writing this, Anne. _The Summer of Her Baldness_ is such an amazing text, all the formal shifts, the layering of personal, cultural, and political—and the mingling of comedy and mortality—and the commitment to community, no matter how imperfect that is. I wish I could see/read everything you’ve mentioned here!