The Good, the Bad, and the Pretty

Jay DeFeo, The Veronica, 1957

In March I went to a party in honor of curator Raimundas Malasauskas’ brief visit to San Francisco. It was held in a two-story condo the Kadist Art Foundation provides for visiting artists—on Bryant near 6th, a dismal neighborhood, but you can imagine how much the thing cost. As chic, gorgeous Europeans and South Americans strolled between the kitchen area and the outdoors balcony to smoke, I stood near the dining room table with Kevin, feeling all stiff and squeaky American. I was delighted when my party buddy, art historian Julian Myers came up to us. The first thing Julian said to me was, “I haven’t read your blog posts.” “That’s okay,” I said. “That’s okay?” he replied, skeptically. I told him how I’d seen Rebecca Solnit’s gallery talk on Jay DeFeo at SFMOMA’s 75 Reasons to Live weekend. Julian made a face and said that he finds Jay DeFeo uneven, that of the two pieces currently on exhibit at SFMOMA, Incision is great, but he hates the other one because it was all about being pretty. “What’s the name of the other one?” he asked. I knew it was a woman’s name. “Bernice?” I offered. That wasn’t it. “Bernadette?” Kevin finally remembered it was called The Veronica. And all of us were like, “What does that mean?” “Is there a Saint Veronica?” I asked. Kevin, our resident Catholic, said yes there was—she was the woman who wiped Christ’s face when he was carrying the cross, and Christ’s face miraculously appeared on the cloth. “Symbolism,” Julian scoffed. “That’s even worse.” I’m there with him, as far as symbolism goes; I’ve often thought of symbolism as a cheap trick that Modernists foisted upon us. Then we bickered about whether or not DeFeo’s most famous painting, The Rose, was pretty. Julian thought it was. The Rose is 11 feet tall and 8 feet wide, the paint is layered on 11 inches thick, and it weighs a ton. “This giant thing that sags and threatens to crash through the floor, how could you call that pretty?” I argued. “It’s not pretty, it’s a monster!” Julian stood his ground. “It’s pretty,” he repeated with disdain.

Ever since my conversation with Julian I can’t quit thinking about the prettiness—and places where it dovetails my favorite subject, female excess. Pretty is helpless and feminine. It has a retro Boomer feel—Sandra Dee, a girl with a face like a flower. Thin-lipped regular features, upturned nose, an expanse of unblemished white skin. Pretty is beauty’s goofy little sister. Pretty is degenerated, there’s nothing lofty about it.

While channel-surfing I recently saw a snippet on tabloid TV about Tanya Angus, a 31-year-old woman who, due to a pituitary gland tumor, won’t stop growing. She’s 6’8” tall and weighs 500 pounds. Angus was a popular teen who looks great in the bikini photo the media likes to display, then at 17 she starting uncontrollably sprouting up. Angus: “I used to be pretty—I was skinny. I was into modeling. I was a dancer. I don’t look pretty now, and I’ll probably never get married, even though that was my dream.” Prettiness is a sort of Eden, encapsulating Angus’ terrible loss.

Jay DeFeo herself was pretty, according to Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times: “She was 29 and already somebody among the Beat poets and painters in the Bay Area: smart, gifted, outgoing, pretty, free-spirited, a bright light on the local scene whom everyone recognized as talented, and, not incidentally, a woman who held her own with the guys.” DeFeo was far from sweet and vulnerable. She worked obsessively on The Rose for eight years, chain-smoking Gauloises and swilling brandy. She’s said to have gotten gum disease from clenching her paintbrush in her mouth—and lung cancer from breathing in lead paint fumes. DeFeo may have been a pretty woman, but hers is a myth of a woman possessed, a powerful woman who sacrificed her body and her social life to her art.

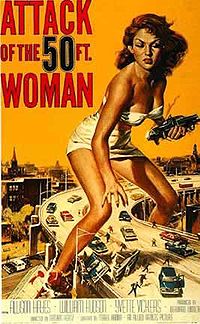

Poster for Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, 1958

Prettiness is an unstable state. A cheating husband thinks he has the little lady all contained in girdle and heels, then a radioactive alien crosses her path, and BLINK he has the Attack of the 50 Foot Woman barreling right at him.

I returned to SFMOMA to reconsider Incision and The Veronica. I stood in front of them with my journal and free-wrote my impressions. I felt awkward, and a bit embarrassed, like I was the embodiment of pathetic geekiness, like people thought I was working on a paper for a community college art history class I was taking in order to fill the lonely hours of middle age. I’d figured that the guards would consider my fountain pen a potential weapon of art destruction and would be tracking me more than usual, but they seemed indifferent as I stood close up and wrote, shuffled to the far wall and wrote, reapproached, stopping intermittently to write. Julian was right, The Veronica is pretty, so pretty it flirts with the decorative, which makes it accessible to a wide audience. I read a blog by one museum visitor—he was an out-of state-guy—who wrote that he didn’t care much for art, but he loved, loved, loved The Veronica. Ve-ron-ic-a—the consonants and vowels dance out of your mouth, syllables you say with a smile, ending with the playful uplifting “a.” In-ci-sion, by contrast, hisses like a snake and slams to a stop. Side by side the two paintings look like bipolar twins. While The Veronica is all soaring fluttery buttercream, Incision is gray and black and thick as mud, a goddess descending to the underworld—or Sandra Dee’s goth sister. It droops downward with sagging paint and strings that dangle like skinny tentacles, like strands of Medusa’s hair. It has the slow, corrosive movement of stone.

Jay DeFeo, Incision, 1958-1961

In The Veronica, the paint is hammered on thickly but within the “normal” range of globby surface-obsessed art. It flows with an upward splash. Red smears punctuate its browns and creams, troublesome dark red undertones that remind me of blood, of dried menstrual blood. The canvas is tall and narrow, like a microscope slide standing on its end, like a close up of a slice of very strange flesh. I have to crane my head back to take in all eleven feet of it. The top of the splash touches an ominous darkness. No matter how far away I stand, I can’t manage to see the whole painting at once. My eye is forced into movement, waves of movement. The more I look at it the more frenetic The Veronica becomes, and I grow queasy. Where’s the center? Its focal point appears to be outside the right border of the frame. Its wide strokes are tiled over one another, suggesting petals or feathers, like it could be a close up of a wing, giant bird’s—or angel’s—wing. As I stare my vision twitches and the movement of The Veronica seems to change, to sweep down and to the right, into the a giant feathery armpit, the armpit of something other, something transhuman. I love it when nonrepresentational art—rather than just standing there in its leaden materiality—sparks off an association feast, a slide show in my mind of images and emotional reverb. In its prettiness The Veronica is more subversive than Incision, which announces something deeper, intense is going on. The Veronica’s creepiness sneaks up on you. Femininity flails its pretty neck and grows monstrous, out of control.

Albrecht Dürer, Sudarium of Saint Veronica Supported by Two Angels, 1513. The angel wings remind me of DeFeo’s The Veronica.

Comments (8)

-

adq says:

April 5, 2010 at 3:41 pm

-

Leah Levy says:

April 3, 2010 at 5:27 am

-

Vance Maverick says:

April 2, 2010 at 8:37 am

-

Brecht Andersch says:

April 2, 2010 at 2:57 am

-

Dodie Bellamy says:

April 2, 2010 at 12:17 am

-

Vance Maverick says:

April 1, 2010 at 11:19 pm

-

Dodie Bellamy says:

April 1, 2010 at 11:10 pm

-

Vance Maverick says:

April 1, 2010 at 11:07 pm

See all responses (8)Thank you Leah Levy! I have copied this to our files/records. –Apsara DiQuinzio, Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture

Dear Dodie Bellamy,

The Jay DeFeo Trust has recently uncovered a letter in which DeFeo states that the proper title of “The Verónica” should have the accent, to be clear that she is referencing the bullfight maneuver, not the female name, in her title.

Leah Levy, The Jay DeFeo Trust

Fair point, Dodie, but as far as I know Kimmelmann is working with the same data we are. (I would put it a bit more strongly than Brecht, especially considering that that film catches her at a low point.) Apologies for the trivial digression.

I understand intuitively the use of “pretty” to disparage a painting, but I don’t myself think that’s DeFeo’s weakness. Rather, I think the expressionism, the attempts at an overwhelming impact, sometimes fall short. (“The White Rose” itself, while great, is notably reserved — the story of her epic labors may knock you over, but the piece itself is a quiet hulking mystery in the form of an explosion.) Also, there are some pictures with an illustrational element that misfires a bit. But “pretty” suggests e.g. Sam Francis, a sweet tooth of another order.

Having seen Bruce Conner’s The Rose several times, I would call her “attractive”.

A photo and the use of the word “pretty” are two different things.

Well, thanks for forcing me to consider alternatives — that one had clicked for me the first time I heard the title, and I was stuck on it.

Tangentially, I’m puzzled that you refer to an outside authority for the claim that she was “pretty”. Was your point to make the claim sound dubious, or reprehensible? There are plenty of photos of her (e.g. in Jay DeFeo and the Rose).

Thanks for your comment, Vance. Yes, the bullfight reference is intriguing. I have notes to go on and on about the name—the cape included, but my post was just going on and on. Had to stop before I collapsed.

A “veronica” is also a pass with the cape, in bullfighting. I don’t see the toro or torero, but the billowing cape is a plausible read for the picture.