Medium or Extra-Large: A Brief History of the San Francisco International Video Festival, 1980–1987

TV Head photograph by Jules Backus, 1981. The “TV Head” image was used as a recurring motif throughout the festivals.

Without the audience, it’s not art, it’s a hobby.

— Stephen Agetstein, director, SFIVF

If one were to trace the origins of video art, one might be tempted to settle for the promethean artist Nam June Paik, who was given “fire” by the Sony Corporation in 1965. Using a prototype for the about-to-arrive ½” reel-to-reel portable video system later known as the Sony Portapak, Paik shot extemporaneous footage on the streets of New York, then played it back in a coffee house later that day — a miracle of insurgent immediacy. This gesture attempted to extricate electronic image-making from the grip of mass media trickle-down. And in fact, Paik had subverted the chain of command, first creating a handmade video image, and then commandeering that domestic outpost of corporate control, the TV set, for its exhibition. But this disentanglement never became a complete divorce — video art remained the lovechild of Big TV, making for a sordid lineage in which its “frightful parent” 1 could taint any artistic effort no matter how unrecognizable it might be to the parental gaze.

Bruce Nauman bouncing in the corner, Joan Jonas flipping through a vertical roll, or Stephen Beck generating globules of color — it was all TV, or maybe anti-TV. Regardless, you sat and stared, and the phosphor glowed on the cathode ray tube. Eventually, video art settled into three or four sub-genres — performance-based, image-processing, guerrilla television, and later new narrative — but the shadow of mass media cast a chill on the proceedings, whether via its production technology, its distribution hierarchies, or its indoctrinating (and otherwise punitive) content. Video artists, meanwhile, scurried about, seeking both exhibition opportunities and that elusive quanta: an audience. For what good were these technological and aesthetic interventions if their subversive pixels had no public presence?

In the Bay Area, exhibitions of what was then called video art 2 were sporadic, inadequately supported, and cloistered within alternative spaces like La Mamelle, 80 Langton, Video Free America, and Tom Marioni’s Museum of Conceptual Art, or within the rarified arena of the more adventurous museums, such as SFMOMA and the Berkeley Art Museum (then the UAM).

And then into the fray came the Mobius Video Festival, a tent show with a medium-invasive, culturally impactful intent. A project of The Public Eye (a non-profit organization supporting public access television), Mobius, which took place in the mid-to-late ’70s as part of the annual San Francisco Arts Festival, offered a vertiginous array of videotapes: one might witness an Oakland blues club on one monitor, an ambitious street performance on another, and the re-enactment of a Chevrolet training film on a third.

For all its commitment to the evolving medium, Mobius was somewhat local in its curatorial reach — not necessarily a bad thing, considering that some truly inventive artists called the region home. Though Terry Fox and Bruce Nauman had abandoned the Bay, peers such as Paul Kos, Howard Fried, Linda Montano, Peter D’Agostino, Lynn Hershman, Darryl Sapien, Doug Hall, and Chip Lord were still very active, and a younger generation was beginning to emerge — a cohort that included Tony Labat, Judith Barry, Max Almy, Jeanne Finley, and Dale Hoyt. 3 What was sorely lacking, though, were showcases with an international scope that could bring representative examples of video art from Europe, Asia, and every corner of our own complex continent. 4

This international scope would be ushered in by Stephen Agetstein, whose videowork about blues great Jimmy Reed had won a Mobius award, gaining him access to Bonnie Engel, guiding spirit of The Public Eye. Engel was ready to pass the Mobius mantle, and saw in Agetstein the entrepreneurial zeal, art savvy, and unfettered energy needed to sustain and (she hoped) grow a presenting organization. But Agetstein was not content to retool an earlier invention. Instead, he created a new organization within The Public Eye, naming it the San Francisco International Video Festival (SFIVF). 5 “International” was an immediate signifier of the festival’s ambitions, suggesting as well a broader literacy around video art’s global sweep.

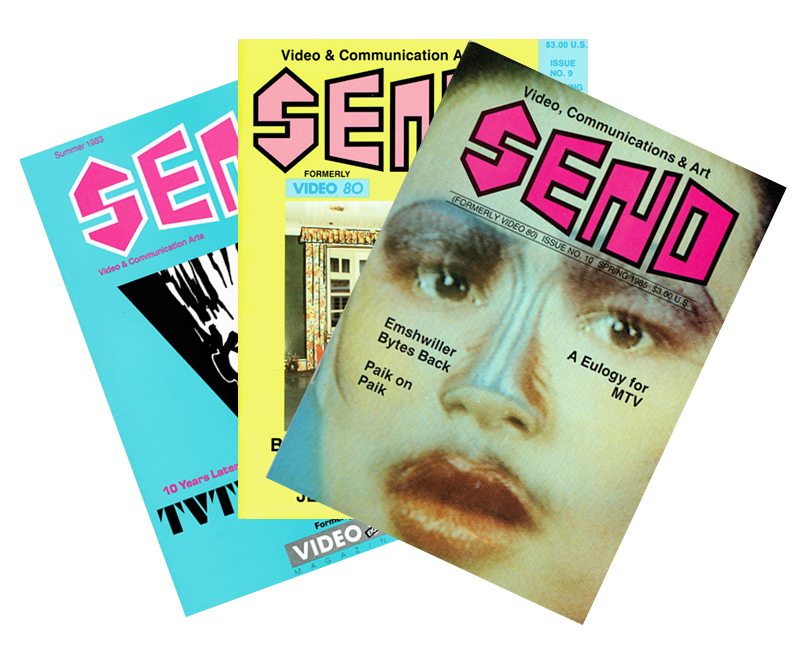

The inaugural issue of Video 80 magazine, 1980.

The SFIVF, nicknamed Video 80 in honor of its inaugural year, would be a triadic project: there would be the festival itself as the central event; Video 80 magazine, an occasional publication that changed titles several times (it was first called Send, then Video and the Arts); and a touring compilation of entries from each year, which, eventually broadened to include VHS home distribution. 6

With few funders on-board at this early stage, Agetstein spent much of 1980 driving a taxi to raise the funds for the inaugural festival in October of that year. 7

Emblazoned on the cover of the first edition of Video 80, the SFIVF issued its opening salvo, penned by Agetstein:

Art in general and video as the vanguard of new art is reaching out in directions traditionally ignored. With few exceptions, art has been available only through the museum, the gallery, and similar spaces. The problem has been the limited exposure the artist finds in such environments…

Art has often been like this, supported and sponsored by select segments of the community: the church, the aristocracy, the corporate hierarchy, the government, what have you. Now many of us feel that a supportive structure can be found in the marketplace. 8

The first program guide for the SFIVF, 1980.

The festival was not rejecting “the museum, the gallery, and similar spaces.” They would remain integral aspects of presentation, but Agetstein excluded them from a “marketplace” that included clubs, cabarets, and a network of other sited and non-sited distribution possibilities, like cable and home video.

All those Beta and VHS machines throughout the country not only are capable of playing independently produced works, but in fact, this is what many of the owners of these machines desire. What is needed now is a framework of exhibition and a network of distribution which will serve to educate this new potential art audience. 9

That hypothetical audience was the Holy Grail of constituencies — an art-friendly mass audience. To pursue it, the festival favored dispersed screenings at venues throughout the City: the Savoy Tivoli in North Beach, La Mamelle, Jetwave, A.R.E., Club Generic along the Market corridor, and Hotel Utah in SoMa. Bigger institutions like SFMOMA, the SF Art Institute, and the Berkeley Art Museum also played along. Some festival works were broadcast on KCSM-TV or circulated by Public Access Channel 25. Its most nomadic venue was a Veteran’s Cab which had a monitor in the backseat.

Illustration by Curtis Schreier.

This dispersal was driven by a thoughtful play of content against context. Internal rhythms, intent, intellectual challenge, and the pleasure principle all came into play: “…there is proper use of the gallery. There are many videotapes which deal with criticism and aesthetics in a manner or with a pacing which will function only in the gallery environment. Also, there are many performance works which depend on the live audience the gallery offers.” 10 The ultimate motive wasn’t to merely tap more viewers, but to disrupt the uniformity and passivity of reception. Agetstein was resisting the “given imperative of the ‘art’ setting” in the hopes that a new relationship between artist and audience could be forged.

This model of scattered screenings persisted for much of the SFIVF’s seven-year run and quickly grew more dynamic as it gained a sure-footedness with regards to audience, funding, and press. 11

The following year, Video 81 took on a more theatrical nature, hosting hefty, cabaret-style events at The Boarding House (where Willie Boy Walker and Joe Rees DJed and Tony Labat’s band, The Puds, performed) and waterborne screenings on the Sausalito Ferry featuring works about landscape.

•

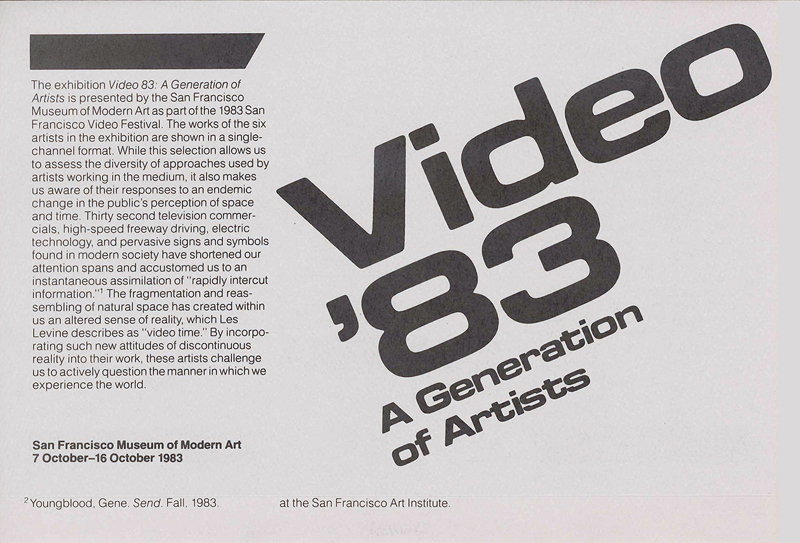

The Festival’s ambitions for decentering an audience and throwing expectation, orderliness, and habit into disarray is difficult to envision without a strong sense of the works presented at the Festival itself. The first year’s offerings — fifty-two video works in total — set a tone that emphasized rigor, diversity, and risk-taking. Selected by a jury of well-known curators Kathy Rae Huffman and David Ross, and artist Paul Wong, twenty-four works were pulled from the entries, along with twenty-eight invited works. (Selected videos vying with the invited would prove to be a contentious issue, especially for Bay Area-based artists.) Though the overall selection was not quite international, it represented a broad and impressive swathe of American artists, among them John Baldessari, Douglas Davis, Gary Hill, Ilene Segalove, Les Levine, Paul Kos, Bruce and Norman Yonemoto, the Kipper Kids, Woody and Steina Vasulka, Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, and Tony Oursler. 12 The essayistic brilliance of Terrell Seltzer and Isaac Cronin’s Call It Sleep, the punk ethnography of Joe Rees’ Target Video, the imagistic gymnastics of John Sanborn and Kit Fitzgerald’s Olympic Fragments, and the performative satire of Michael Smith’s Secret Horror illustrated a mastery of the tools of video art, and included enticing subject matter that might stand some chance against “the competition of the channel selector.” Not that these works were ready for prime time, but they had forsaken the raw assault on expectations and craft that seized many first generation video artists.

It was an unspoken assumption of the SFIVF that coaxing and educating an audience for challenging media art required engagement with Festival events — retaining this audience, ultimately, depended on the inherent excitement generated by the works themselves. This populist aesthetic nonetheless tended to favor more “accomplished” works, which some critics of the Festival thought confused production values with meaningful cultural expression (a dilemma unresolved through the festival’s final days). Video 80 magazine could be seen as complementing the desire to expand its audience through demonstrable professionalism, just as the most polished of videoworks might. The tabloid-sized publication had edgy but elegant design (often rendered by Chip Lord), brilliant artists’ pages, and provocative editorial content.

Published by Wendy Garfield, 13 the occasional periodical consolidated much theoretical thinking about the future of the media arts. Willoughby Sharp on artists’ use of satellite TV, H. Whitney Bailey on interactive videodiscs, Francis Ford Coppola on electronic cinema, Larry Cuba on computer animation — one might be tempted to say Video 80’s indebtedness to publications like Radical Software and its tenor of technological ecstasy was evident. But a small coterie of contributors broadened the publication’s purview to include considerations of video art as a contemplative object and cultural artifact. 14 Particularly thoughtful musings by Bill Viola, Doug Hall, Gene Youngblood, Marian Kester, Juan Downey, and Michael Naimark, among others, anchored video art to an art-historical terrain that was more philosophical and subversive and less about technology. In all, eleven issues were published, the last tellingly retitled Video and the Arts. As artist and contributor Doug Hall said, there was great importance in providing a “space for critical and even whimsical voices from scholars, curators, artists, etc. In some ways early video was as interesting as a discursive vehicle after the fact as it was a material to be viewed.” 15

By late 1983, the SFIVF had taken over the former Rip Off Press offices at 17th and Missouri, giving it a home base. Dubbed the Video Gallery, the festival could now offer ongoing screenings, relieving the annual event of its premier status.

But also, consider this: the gallery name itself was a provocation. A few media artists (Nam June Paik, Gary Hill, Bill Viola, et al.) had found substantial support within the museum and gallery system, but that patronage was truly the exception — painters and sculptors still ruled the roost. Videotape as a collectible medium was considered too ephemeral, and the exotic, cranky, and expensive hardware required for installation discouraged purchase. Even quintessential collectors like Pamela and Richard Kramlich didn’t purchase a videowork until 1987. 16 The self-proclaimed “video gallery” declared that moving image media had a primary place within its whited walls. At least on that quiet corner in Potrero Hill, video art, or “the electronic chisel of our age,” as Agetstein called it, had replaced painting and sculpture. 17 18

Two successive iterations of the festival (1983-84) made use of the Video Gallery as their principal site, though the tradition of scattered screenings continued. Then, in the fall of 1985, the festival was once again homeless, 19 resorting to venues like the Palace of Fine Arts, New Langton Arts, Club Nine, and SFAI. Highlights from that year included Marina Abramović and Ulay’s Terra Degli Dea Madre, Gary Hill’s Why Do Things Get in a Muddle, Tony Oursler’s Evol, and that powerhouse of paranoia, Michael Klier’s Der Riese.

Cover of the architectural prospectus for the final Video Gallery, 1986.

An interior page from the architectural prospectus, 1986.

But the real action was elsewhere in 1985: after SFIVF suspended its open competition, complaints of elitism (already harbored by many local artists) reverberated throughout the community, inspiring local artists Niccolo Calderaro and Susan Kuchinkas to start a counter-festival with no curatorial gateway. Though Video Refusés, as it was known, eventually gave in to curatorial prerogatives, the defiant mini-fest outlived its own frightful parent. (In the December 1985 issue of Afterimage, Bay Area-based critic Christine Tamblyn aired in some detail the in-grown nature of the SFIVF.)

From the 1982 SFIVF. Illustration by Curtis Schreier.

Meanwhile, if the original Video Gallery couldn’t accommodate the ambitions of the SFIVF, perhaps a larger space in SoMa could. The Festival found a 6,400 square foot warehouse which it occupied in the summer of 1986. This raw space required massive renovation and soon architectural plans were formulated for a complex that would include enclosed gallery spaces (some for privately viewing video works), a large open gallery for projected presentations, an unbroken fifty-foot gallery wall for hanging art, and, facing Howard Street, the Café Schlemmer. 20 This new venture was Video Gallery writ in bold and italic as it bravely leaned toward the future.

While the renovation bumpily proceeded, 21 the festival’s grand finale took place. It included Belgian artists Frank and Koen Theys’ monumental re-invention of Wagner’s Ring Cycle prologue; Lowell Darling’s Hollywood Archaeology, accompanied by film noir heavy Mike Mazurki’s reading of juvenile poetry; and Bill Viola’s virtuosic exploration of consciousness, I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like that not only astounded festivalgoers, but garnered San Francisco Chronicle art critic Kenneth Baker’s first video art review. Back at the construction site, the Video Gallery offered four installations, early video sculptures by Alan Rath, projected pieces by Jeanne Finley and Chip Lord, and George Kuchar’s first installation, a mock motel room, complete with bad art, dirty laundry, and overstuffed couches, within which he screened Weather Diary 1.

Kuchar’s Weather Diary 1 offers a prescient image: a solitary man standing in a doorway, great storm clouds gathering in the distance. Burdened by escalating costs for the renovation, scandalous building inspections, administrative tasks impossible to shoulder, and a marital implosion, Stephen Agetstein called it quits in the spring of 1987 — the sound of hammer and saw fell silent, and the San Francisco International Video Festival ended. 22

•

Was the demise of the SFIVF a product of ill-conceived ambition? Or prophetic ambition come too soon? Only pure speculation can account for an alternate past, one where the Video Gallery thrives and video art nudges its way through a door once guarded by those two bouncers, painting and sculpture. But that possible variant never arrived.

What did happen was the slow but continual absorption of video art within the extant system, showing it to be a feisty medium that wouldn’t push much aside, but instead would begrudgingly fill out the ranks. Starting in 1987, SFMOMA, guided by Robert Riley, founding curator of media arts, lunged heavily into time-based artworks, purchasing works by significant artists in the nineties, including Bill Viola, Tony Oursler, Steina, Doug Hall, Matthew Barney, Vito Acconci, and Julia Scher. Supplemented by generous loans from the Kramlich Collection, SFMOMA’s hefty exhibition schedule, topped by Seeing Time in 1999, presented the Bay Area with a critical mass of media-inflected work.

This upsurge in visibility stimulated an increase of interest within commercial galleries, which in turn began expanding their artist stables with established media art practitioners. By the new millennium even emerging artists would find themselves courted by gallerists in pursuit of the next big thing. And those ever stalwart incubators and polymorphic spaces like New Langton Arts, The Lab, Southern Exposure, Capp Street Project, and Artspace 23 continued to vigorously support new waves of electronic innovation. 24

What can be said, definitively, is that no other festival came to fill that arcane niche of video-only exhibition. 25

But the festival model was not the intended end-point anyway. The SFIVF sought a paradoxical goal, a medium popularized through public festivities then neatly placed within the rarified walls of a gallery. Perhaps this sequestration was counter-productive. If a medium is to support wild growth and innovation, it must be exposed to the contaminants of culture, not hygienically sealed in a clean room.

Finally free of its frightful parent, video art is now on its own. An orphan? Or an adopted child? But definitely a co-equal in that cohort they call the arts.

•

There’s a childlike exuberance to video art that seems to have gone out of other forms of self-expression. The artists don’t have great traditions and models to work from — or against. They are pioneers striding that amazing plain where modern technology meets art, emitting cries of discovery and joyous wonder… But the great thing about the video artists themselves — and the people who mount the San Francisco International Video Festival — is their complete disregard for the verdict of posterity.

— Bill Mandel, San Francisco, October, 1981

This essay was only possible with the generous input of numerous people involved with the SFIVF, including (and especially) Stephen Agetstein, Wendy Garfield, Dale Hoyt, Doug Hall, Chip Lord, Lowell Darling, Bonnie Engel, Darryl Sapien, Paul Kos, and Tony Labat. Much thanks is due.

- David Antin coined this phrase in a 1975 essay published in Artforum, though he describes the art form’s birth “from the Jovian backside of the Other Thing called television.”

- The “video” in video art would eventually fall out of favor and be integrated into a more innocuous descriptor: media art.

- My pre-emptive apologies to those valued artists not named here.

- Of the extant video art exhibition programs, David Ross’s screenings at the Berkeley Art Museum were probably the most eclectic and far-reaching. A seminal video curator, originally from the Everson Museum in Syracuse, NY, Ross was an influential advisor to the SFIVF in its first years. He would return to the Bay Area in the late ’90s for a short stint as director of SFMOMA.

- Full Disclosure: I was affiliated off and on with the SFIVF as a volunteer editor of Video 80 magazine and eventually as part of the miniscule staff.

- Home distribution was a noble but inadequate effort. Several worthwhile titles, such as Nam June Paik’s Allan ‘n’ Allen’s Complaint, Daniel Reeves’ Smothering Dreams, and Meredith Monk’s Ellis Island were nicely packaged but not broadly circulated.

- Agetstein was a hack — a driver of cabs, that is, at least while getting his bearings after attaining an MFA from Lone Mountain College; renowned for its progressive art department, Lone Mountain College was acquired by the University of San Francisco in 1978.

- This is from an opening statement that begins on the cover of Video 80, Vol.1, No. 1 and continues on Page 1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Agetstein was very successful in his relationships with the press. Staff writers Bill Mandel (television columnist, San Francisco Examiner), Steven Winn (general culture, San Francisco Chronicle), and Jerry Carroll (general culture, San Francisco Chronicle) regularly covered the festival. However, the art critics at both dailies generally ignored it.

- Additional artists not mentioned above would become mainstays of the SFIVF. I’m thinking of Lowell Darling, Chip Lord, Doug Hall, Howard Fried, Peter d’Agostino, and others.

- Garfield was Agetstein’s wife and an inestimable force behind the festival.

- A strange quirk of Video 80 was its nom-de-plumed columnists. They can be decoded thusly: Dr. Telecom was Willoughby Sharp, Dr. Ray Orbison was Lowell Darling, Natalie Welch was Dale Hoyt.

- From an email exchange with Doug Hall, February 2017.

- SFMOMA would hire its first Curator of Media Arts, Robert R. Riley, soon after.

- From an interview in City Arts Magazine, Summer, 1980.

- Ironically, the most memorable event in this space was not a video screening or installation but a 1984 exhibition that ran from June through August: Artists’ Olympics: Miniature Golf, a playthrough course coinciding with the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Magnificent holes designed by such astute duffers as Chip Lord, Phil [Pippa] Garner, Tony Labat, Tom Marioni, and John Woodall gave players a discombobulated form of Putt Putt. But it was Howard Fried and Paul Kos who cast the venerable game as an existential encounter. Fried’s graceful dogleg, covered with plush white felt, had no hole whatsoever; you were released from the tyranny of par. Kos, on the other hand, offered a guarantee of success in his massive ice-block that required putting on crampons for your icy putt. Constructed with a slight tilt, the ice would melt toward the hole, assuring the patient golfer of a hole-in-one.

- A two-year lease was unrenewable.

- The café’s name was a “nod to the sculptural origins of fine arts performance (as in: not theatrically based) and by extension video performance and extended a bit further to the Video Festival.” From already cited email exchange with Agetstein.

- Funded by substantial grants from the SF Hotel Tax Fund.

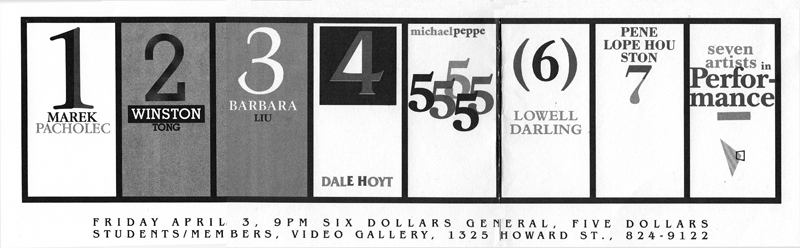

- The final public event, held April 3, 1987, in the Howard Street space was Seven Artists in Performance (Lowell Darling, Penelope Houston, Michael Peppe, Dale Hoyt, Winston Tong, Barbara Liu [McDowell], Marek Pacholec), a benefit for the building project. Three hundred and twenty-four tickets were sold.

- Several of these alternative galleries no longer exist but were highly influential throughout the eighties and nineties.

- Perhaps my own weekly screenings at the Pacific Film Archive, beginning in 1988, would be counted as a stimulus?

- The Mill Valley Film Festival had the Videofest, a satellite venue that never shared in the hoopla or stature of the main film program. Once “video art” had found more acceptance, the festival simply dissolved the Videofest into its ranks.