So Going Around Cities (Quarantina)

From the Wite-Out series, Linda Norton, 1993–1994.

And now I’m with you, instantly

& I’ll see you tomorrow night, and I see you constantly, hopefully

though one or the other of us is often, to the body-mind’s own self

more or less out of sight!

Ted Berrigan, from “So Going Around Cities”

Linda Norton, 2015.

At the beginning of March I went out to dinner with my daughter for what I now know might be the last meal I eat in a restaurant for a long time. We stopped into the parking garage in Jack London Square, where my friend Ivory was working in the booth at the in-and-out gate. When she saw me she came out of the booth and gave me a bear hug. I had stopped touching people because I’d been sick and was afraid I might be contagious, but I hugged her back.

Ivory is a friend from the Oakland YMCA. The Y has been “my third place” for decades —my congregation, my sangha. My second book, Wite Out, includes many scenes set there.

I miss the life of streets, locker rooms, parks, bars and restaurants and dinner parties, libraries and bookstores, trains and train stations, and visiting my friends in New York and Ireland. I miss the women, and the occasional man, at the nail shop where I get pedicures. I miss ordinary errands, and I miss touch.

Nail Today, Grand Ave., Oakland

Late-night homework, 19th St. BART Station, Oakland.

Here are some excerpts (see my March post, “The Martyr Poets,” for others) about public and private serendipity, schooling, and intimacy, the way things used to be for me.

2001

September 11th. In the pharmacy, collective sadness, silence, except for an autistic boy who’s waiting with his grandfather for a prescription. The boy is screaming and crying, the old man is holding him tightly and tenderly. No one looks right at him. Nor does anyone move away from him.

Isabel’s poems this week:

MOM

This living

creature walks

around The

house not

knowing what

to do.

ISABEL

This wonderful

creature walks

around the house

Throwing Back her

Pearls

Governor’s Island, New York, 2012.

2002

“What is death?”

The day they ask. Or the day you have to tell them —

I was looking at a picture album with her on the couch, showing her the one of Nonie with Pa, fresh off the boat, posed in finery.

I turn the page to the pictures of us kids. I say each of our names. “Linda, Caroline, Richard, Joey, Michael.” I notice for the first time that Joey’s standing next to me in each of the pictures.

“The little kids,” she says. “And you were the big one.”

Today I drove around and around, focused intently on trying to find a place to park on Lakeshore.

“Mama,” she said from her car seat, watching my face in the rearview mirror, “are you sad because you’re thinking about your brother who died?”

“No, honey,” I said, astonished. “I’m just worried because I can’t find a parking spot.”

Grand Lake Theater, my neighborhood, Oakland, 2019.

2003

Reading on my blanket, missing Isabel while she’s with her father, I fall asleep in the rose garden near a bed of American Beauty roses. Across the path, they are setting up for a ceremony. A wedding harpist shows up and flirts with a kitty in the grass. “Ooh, you’re so fat, who feeds you?” This place is like something out of Disney today, but someone was attacked at the top of the garden last week.

“Do you speak Farsi?” asks an older wedding guest who’s lost.

“No,” I say, accustomed to being mistaken for Iranian (or Greek or Lebanese or whatever) because of my dark hair and eyes and eyebrows.

I tell her that I got the darkness from both sides of the family.

“You’re Irish and Sicilian, what a combination! You like to drink, you have a bad temper?”

Yes and yes. But I had a fuse so long that I didn’t explode until I was thirty-seven.

The harpist’s name is Olga. She comes from Odessa. The police interrupt us to tell us she must move her harp.

“Are you married?” Olga asks as she lugs the thing. When I say no, she’s puzzled. I get this a lot. I still don’t really know how not to be married.

After the reading at 21 Grand I went home and cooked tortellini for Isabel. We sat talking at the table. She chewed thoughtfully.

“Isn’t it funny,” she said, “that when you’re thinking and talking, one thing makes you think of another thing and then another thing?”

“Yes. There’s a name for that — stream of consciousness.”

“Oh,” she says. “I have that a lot.”

My baby, my notebook.

2006

Day after New Year’s. Alone and blue. I woke up at dawn and went to the Y. I was wearing sandals and my hair was a mess and it was pouring rain. I had to park far away. By the time I got to Broadway I was sopping. As I came around the corner, I bumped right into a young brother.

He backed up and looked me up and down, trying to find something, anything, to admire about me, and said politely, “Pretty feet.”

I scowled at him. He looked hurt.

He squinted at me in the rain. “I was just trying to be nice.”

“I know,” I said. “But it’s so cold, and I’m so tired.”

—

On the way home from work I passed a handwritten sign in front of the barbershop: “I can weave a bald head.”

If he can weave a bald head, I should be able to make something of my failures, my mess.

Grand Ave., Oakland.

2008

At the Y Maggie and I sat in the hot tub after I cleaned it with a wad of toilet paper. There’s always grime around the rim.

“They don’t give a shit about us here,” she said in that gravelly voice I love.

Things are always broken and dirty in our locker room.

“Do you think it’s like this in the men’s locker room?” I asked.

“How would I know?” she said. “I stay away from men.”

She’s seventy-one years old and does freelance hospice nursing for even older women. This week her favorite patient died.

“Baby, I can’t take much more of this at my age. And I don’t need the money. I got a pension and Social.”

She talked about her mother who died of cancer before she could move back to Louisiana like she wanted to. Maggie nursed her, too.

As I climbed out of the hot tub she looked frankly at my curves and said, “You got it, baby. You look like I used to look when I was young.”

Young? I’m forty-eight. Strange to think that someday I might look back and think of these as salad days, despite my fat thighs and cellulite and the creases on my forehead.

Maggie looks like Billie Holiday would look if she’d lived to old age. Beautiful and tough.

She climbs up out of the tub behind me. “That’s a pretty bracelet,” she says. “Is it ivory?”

“Oh, God, no. It’s plastic. I bought it at H&M for $5.00.”

“I love ivory. I used to work at an engineering firm and there was a man there who would bring me ivory things from Africa.”

She was married once, long ago.

“Nothing in it for me,” she once told me, dismissing the institution, and maybe men in general, with a wave of her hand.

Downtown Oakland YMCA.

At the water fountain in the gym, I hear a voice in my ear, a sweet growl. It’s Cleo. I haven’t seen her in a while. Her daughter goes to school with Isabel. Together, last year, she and I taught a six-week class to the third grade to fulfill our volunteer hours at the school. She’s also a single mother.

“Oh, hey! Great to see you.”

“I was checking you out and I said to myself, that is a fine-ass white woman, and then I realized it was you.”

“Thank you, Cleo. You look great.”

“Oh, yeah,” she says, gesturing toward her slender legs and slapping her little butt. “White dudes love me. But the men I want like what you got.”

She looks like a model, slender and elegant. She’s about ten years younger than I am. Grew up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and works at Kaiser in the billing department.

She grabs my ass and I laugh.

“You know,” I say, “it’s a good thing you turned out beautiful, being named Cleopatra and all. Because it could have been awkward for everybody if you were named Cleo and turned out ugly.”

She laughs and tells me a joke from the Queens of Comedy DVD about aspirational baby names and an ugly toddler named Denzel. I’ve seen it — Wanda gave it to me for my birthday.

We talk about another stand-up routine on that DVD. The one about getting dickmatized.

“No, no, no.”

“To be avoided!”

“Never gonna happen.”

On the other side of the stairwell that guy Johnnie is talking about something serious with the haggard-looking white guy and trying mightily not to look my way.

But then our eyes meet.

I turn to give Cleo my complete attention.

Linda Norton, FSA series, 2005.

Back at my desk. I need to focus, to read and write, but I can’t concentrate; thinking about Johnnie.

Last night I thought I spied an emoticon in The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore. The other day I found a rose petal in my cleavage when I got to work. I have no idea where it came from. I haven’t been near roses.

—

On the way to work I see a little girl on the corner of Telegraph and Hearst holding a seashell to her ear: “Wow, how does it do that without batteries?”

Her brother grabs it and holds it to his ear: “I hear a toilet flushing.”

A walker in the city.

At the taqueria in Montclair today, one of the Mexican laborers came in with a shopping list written faintly on a scrap of wood from the construction site. The men in line look like gods with noble noses and scuffed shoes and plaster in their hair.

—

At Walden Pond Books, a guy down on his luck is trying to sell books — battered guides “for Dummies” and a beautiful old volume with embossed covers.

The seller holds the book up. “Would you take something like this?”

“Sure, I like to keep a Quran or two around when I can.”

Bookstore, Skibbereen, Ireland.

At the gym after another demoralizing day at work, I was getting my things out of the trunk on a dark street and suddenly there was a man right behind me. “Excuse me, ma’am —”

I recognized him. I’ve given him money before. I said, “Jesus, don’t sneak up on me like that! That’s not right.”

“Are you scared of me?”

“YOU should be scared of ME. I had a bad day at work and I’m in the mood to take it out on someone.”

He smiled a toothless grin and pointed at my pink crystal pendant. “Yeah, I can see you’re a witch. A GOOD witch.”

I laughed.

“That’s nice, too,” I said, pointing at the ankh around his neck as I dug into my pocket.

On the car radio on the way home I listened to D’Angelo singing “Devil’s Pie”:

Ain’t no justice

Just us

“Every woman who has ever kept a diary knows that women write in diaries because things are not going right.” — From Mary Helen Washington’s introduction to the Memphis diaries of Ida B. Wells

The perfect book, one in which I write between the lines.

2012

Taking a six-week meditation class with twenty other people in an upstairs corner room in a Julia Morgan building. Friday afternoons for three hours. It gets dark early and it’s awfully cold in there. We spread out on mats with woolen blankets that smell like sheep. I want to cultivate equanimity. But all I do is cry. It’s almost Christmas. Those children slaughtered in their classroom in Sandy Hook —

Sometimes in class we sit in a circle and people talk about their efforts to manage chronic pain and depression and anger. One guy tells an anecdote about an episode of road rage, which dissipated when he realized the other driver was a beautiful woman.

—

In the hot tub at the Y tonight — my hips are aching. A woman climbs down the stairs into the water and wades toward me, smiling. I’ve seen her many times in this locker room, but we’ve never spoken.

“Hello,” I say. “How are you tonight?”

“I’m celebrating! A birthday, a book, a lifetime. Praise Jesus. Can you guess how old I am?”

“Well that’s a trick question if I ever heard one. Sixty?”

“You know black don’t crack! I’m seventy years old. And for forty years I’ve had my own catering business. I just published a book about my life in the food industry. My friends threw me a party at Scott’s. Look me up on Facebook and you can see the pictures.”

“You’re a writer? Me too.”

She has the most beautiful eyes and dimples. Like Vee, and like my sister. They’ll all be pretty girls until the day they die.

She tells me about her granddaughter who just had successful bariatric surgery. “She takes after me, but it took me a long time to get this big. She did it by the time she was sixteen.” She talks about the food her parents ate growing up in Louisiana and the way kids eat now.

She says she wants to write another book.

“What about?” I ask.

“I’m calling it ‘The Mess in Christian Life.’”

“I’m Linda,” I say. “What’s your name?”

“Reverend Esther, but you can call me Esther.”

“Oh, where is your church?”

“Wherever I am. Wherever I am, that’s where my church is.”

“So we’re in your church right now? In the water?”

She smiles and nods. I stand up straight and she squints and looks at my chest.

“That’s a nice necklace,” she says. “I like the beads. The color of water. But you know,” she says, “I think you could be getting more out of them beads.”

“I have to jump in the pool before it closes,” I say, climbing out of the tub.

“Next I see you I will give you my book and you’ll learn about my life.”

After my swim I heard her calling my name in the locker room and I found her at the sinks.

“Oh you’re still here,” she said. “I thought you’d gone.”

She opened a small velvet pouch and shook a tiny cross, an ankh, and a little bottle of oil onto the counter. “I want to give you a blessing,” she said.

“Okay,” I said, and she took my hand and rubbed some oil on the back of it and bowed her head.

A minute later she was back to business, wiping her hands with a paper towel and packing up.

“Thank you,” I said. “What should I do now?”

“Whatever you have to do, baby.”

It’s always been like this for me in Oakland, from back in the day when I was a waitress at Mavis the Pie Queen till now — people praying over me and around me.

There must be two hundred tiny churches in East Oakland. In a driveway near Havenscourt I once saw a tool shed from Home Depot adorned with a cross. In this town, if you hear the call, you can start a church (or be a writer).

14th Street, East Oakland, Palm Sunday 2020.

2013

After meditation classes ended, I thought I might try going to Sunday Mass for several weeks in a row. I call myself an ex-Catholic, not a lapsed one, but I still cross myself at news of the unspeakable. The gesture and the rituals are encoded in me. I used to go to daily Mass in college before I lost my faith — that was my meditation practice, I guess.

So I’ve been going to St. Michael’s, a Black parish in West Oakland. Harry knows the pastor there, a black Jesuit who used to teach chemistry at Holy Cross. I decided I’d commit to three weeks in a row and see what happened.

Marcus [my son, who came into my life through the foster care system when he was a teenager] came to Mass with me this week — arrived late, caused a bit of commotion, and sat down next to me.

He whispered in my ear: “I couldn’t find this place at first. I went into a Korean church and I told them, ‘I’m looking for my mom, Linda.’ ‘No Linda! No Linda!’ They practically pushed me out the door.”

Marcus had never been in a Catholic church. He looked at the people in the pew in front of us. They had a kneeler — we didn’t.

“Why do they get a foot rest and we don’t?” he said resentfully.

“That’s not a foot rest, that’s a kneeler. Shhh.”

Marcus whispered running commentary, not paying attention to Greg (Fr. Charles; but I can’t call any priest “Father” anymore). The priest glared at him, inspired, as he sermonized about sin and sex.

I whispered to Marcus, “Show respect and listen to him. I hear he has a PhD in chemistry.”

“Well, I guess you have time for that kind of stuff if you’re not getting laid.”

I suppressed a laugh.

After Mass we drove over to a crumbling wall near West Oakland BART where he tagged last week. His tag, JOOS, in enormous blue letters.

—

This Sunday Greg started his sermon by mocking a girl who’d come to a memorial last week in those outrageously high heels everyone wears these days. He impersonated her tottering up to Communion, proud of herself, and I was embarrassed for all of us. The cruelty, the misogyny — so familiar. I looked around at the other parishioners. A few were laughing along.

I left before Communion.

—

So isn’t this funny: I decide to go to Sunday Mass for three weeks in a row for the first time in thirty years, and the right-wing Pope resigns. Big news! First time a pope has resigned since fourteen something something.

Co-incidence? I don’t think so.

St. Elizabeth’s, East Oakland, 2019.

My last day with Isabel in Portland before she starts college. Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day” came on the radio as we finished our goodbye lunch, and I gave her money to go up to the counter and pay the check. I didn’t want her to see me cry. Otherwise I kept my composure. Until I got to the Portland airport. I hadn’t eaten much of my lunch and I thought I should get a sandwich for the plane. But I couldn’t figure out what to get. The girl at the counter offered to help me choose a sandwich.

I said, “You know, I feel like I just have to tell someone that I’m a single mother and I just dropped my only daughter off here for freshman year of college.”

She said, “Oh no! My mom is single too and we’re so close. I can’t leave her, I decided to go to a junior college and commute. I love her so much!”

She burst out crying and so did I.

“Poor us,” I said, hugging her. “Lucky us.”

—

Was feeling out of touch, so lonely for Isabel now that she’s away at college, so I called her in the middle of the day. She was in bio lab. She said, “I was just thinking about you.” I said, “What were you thinking?” She said, “Mamamamamamamama.”

2014

Went to meet Marcus at the BBQ place where he works (it’s called Perdition). The dishwasher greeted me with a smile and told a waiter, “That’s Marcus’s mom.”

“He’s in the freezer,” said the waiter, and turned to walk me to the back.

“Oh, I know where it is,” I said, and went down the corridor and opened the door of the meat locker.

He was in there with all the carcasses. “Look,” he says, showing me a cow skull. “I’m gonna dry it till all the meat falls off and then I’m gonna paint it.”

“Come out, it’s so cold. Let’s eat.”

We went next door and talked about this week in policing. He tells me about a cousin of his grandmother or a great-uncle or someone in the family way back when who did the impossible — killed a police officer in self-defense and got away with it.

The stuff of legend?

“No,” he says, “it really happened!”

Then he tells me about a time someone shot him.

“So we’re in the recycle place in Oakland and there’s this little white kid, and he sees me, and next he’s going crazy, digging through all the bins, all the junk, and finally he finds it, like he always knew it would be there: a little plastic toy gun. And I’m just sitting there minding my own business, and this kid comes over and points the gun in my face, and bang!”

Women’s March, January 21, 2017, Oakland.

I drove him home, past the crumbling wall near West Oakland BART where he tagged last week.

“Why is JOOS your tag?”

“You know — JOOS. Like O.J.”

He looked at me, puzzled—how could I not know—after all this time?

“JOOS like Juice? Like O.J. Simpson?”

“Yeah.”

Of course. Why hadn’t I thought of that?

Because I’m white, I had forgotten that O.J. was a hero to many.

That day when O.J. led the police on the Bronco chase in LA, I was on a business trip in DC, sitting at the bar of the Tabard Inn, drinking ginger ale. Everyone was staring at the TV. I didn’t understand what the big deal was.

Marcus was five when Simpson did the impossible and beat the system.

Now I tell him about O.J. in the Hertz commercials. Back when O.J. was lighter. He doesn’t know about that part of Simpson’s life.

In the car a few years ago, on the way home from a court date, he read me a poem he wrote: “Since I was nine / I have been an immense black man / to everyone I see.”

Marcus.

Terrible headache. Went to the gym anyway.

Roxanne, my pal the evangelist, stops to proselytize me while I’m showering.

Her eyes glitter as she talks about Christ’s suffering on the Cross. “Pastor says it was even worse than it was portrayed in the Passion of Christ,” she says happily.

I go into the sauna and close my eyes. On the benches around me four women are talking and I think I hear one of them say, in the midst of a rapid-fire burst of talk: “When I was in Dachau.” But then I realize they’re speaking Chinese.

Putting on my makeup, my foundation at the counter at the gym, it looks like I’m rubbing whiteface on my cheeks and forehead.

Am I having a migraine? I’m hearing voices:

“Do you ever have ‘lyric episodes?'”

“Like small strokes?”

Yes, if I’m lucky.

—

To Marcus’s place on West Street to bring him spaghetti and brownies. Harrell was there. I had to pee so they went into the bathroom (they keep it sparkling clean) to jiggle the plumbing for me. I’m proud of Marcus for paying rent, for having a job and his own apartment and furnishing it with things he’s picked up on the sidewalk and carried on his back — two dressers and two couches.

When I came back from the bathroom their pet lizard was walking across the hall. Marcus scooped it up and cuddled it.

He has a huge TV in his room. He showed me how you play his video game. “There are never any little kids in video games,” he said. “So if you shoot someone in the head, you know it won’t accidentally hit a baby in a stroller.”

On the wall there were paintings he’d made, and a picture of Lil B, along with a few collages I’d given him and a note I’d sent him long ago.

He wanted to go to an anti-gentrification party at the people’s park on San Pablo. I told him I didn’t want to go — “I’ll be the oldest person there by thirty years, I’m sure.” But he insisted, so we drove over. They were barbecuing tofu and making vegan pizzas in the handmade stone oven and painting a mural that says “Afrikatown.” He introduced me to everyone as his mom. No one batted an eye.

I wandered off to the tables staffed by tenants’ rights advocates and I saw a couple I recognized — those people who took my bed off the street after I listed it on Craigslist. Now they have a baby.

I recognized a guy I know from campus, a student journalist. I had helped him with his Africana studies research in the library a few times in his freshman year. Since the murders of Michael Brown and 12-year-old Tamir Rice, I’ve read some of his work in a local Black paper. Now he’s writing about separatism as the answer to the problems of our time and place. The problems that never go away in America.

He looked at me, more wary than friendly, and said, “Hey Linda.” I was surprised he remembered my name.

Marcus stood nearby, talking about evictions with a volunteer lawyer and listening to every word. He notices and remembers everything; he could be a detective. He has scrutinized me from the very start. He seems to remember everything that I or anyone else has ever said to him. Now he scrutinizes everyone who talks to me.

“Hey, how are you?” I said to the guy from the library. I thought his name was Trey, but I wasn’t sure. “Forgive me — remind me of your name?”

“Rashid,” he said

Marcus tugged at my sleeve.

“Let’s go. I’m bored. And I’m hungry.”

“How can you be hungry?” I said. “You just ate a quart of spaghetti.”

I introduced them. “This is Marcus. Marcus, Rashid.” They nodded at each other.

“Gotta go,” I said. “Nice to see you.”

We walked toward the gate and the burrito shop. I said to Marcus, “You know, I think the last time I saw him his name was Trey.”

“We’re in Afrikatown,” he said drily. “If we stayed five more minutes, you’d be Rashida.”

![]()

![]()

At one point, for instance, I drove in the company of a black family for a good half an hour. They waved repeatedly to show that I already had a place in their hearts as a friend of the family, as it were, and when they parted from me in a broad curve at the Hurleyville exit — the children pulling clownish faces out of the rearview window — I felt deserted and desolate for a time.

— W. G. Sebald, The Emigrants

Driving around Lake Merritt last Sunday I almost rear-ended the car in front of me when it stopped short at a light. I didn’t beep the horn or anything, I wasn’t mad; I was just grateful that I’d been paying attention. And I was curious. I pulled up alongside the car to get a better look.

In the front seat was an old Chinese man and in the back was a woman I took to be his wife. There were quince branches on the dashboard, branches pressed up against the glass of the windows, branches from floor to ceiling, branches all around their faces. The car was a battered grey sedan held together with duct tape, like my car.

These elderly people were entirely surrounded by spiny branches but they weren’t shielding their eyes with their hands or driving carefully. It was as if only I could see the danger they were in.

California Hotel.

More killing and more protests and “riots” this week, here in Oakland and everywhere. I was going to meet Marcus near City Hall and eat at Xolo last night, but downtown the glass from shattered car windows (from the last protest) still glitters in the streets, and I can’t risk damage to my car.

So I picked him up on West Street and we drove around slowly, watching the police setting up barricades. Then we went to my place and made spaghetti and listened to the helicopters hovering. I put flowers in vases. He sprinkled sugar in the water to make the flowers last longer. Something I never do. “Thank you.”

I microwaved the bread pudding I made last week. Then we sat on the couch with my computer, looking at Yelp reviews and music videos. Next he showed me his friend’s funny nude pictures on FB (oh no). Time to say goodnight.

Outside, on the front steps, we looked up at the helicopters that circle every time something happens in Oakland. Marcus took out his green laser beam and pointed at the stars.

I drove him back downtown and we talked about looting. Last year he told me that he’d grabbed some shoeboxes from a store on a night like this. I used to be shocked when I watched such scenes on the news. Now I don’t see things the same way. I’m worried about him, not the property, and I hope he won’t do it again. I don’t want him to get hurt.

I dropped him at his place and he leaned into my window to kiss me. A police car sped past us with lights flashing.

“Bye,” he said. “Look for me later on the news!”

I laughed.

“No. Go play a video game.”

He waved and smiled as he walked away.

“I love you,” he called out.

I waited for him to close his front door before I drove home through streets filled with police cars and barriers.

Isabella Street at West Grand; empty streets, March 2020.

2016

My birthday. I make a plan for friends to meet me at Brennan’s. I invite Marcus and am a little surprised when he shows up. He came to my CCA lecture, too, and he spoke up. At Brennan’s he bends down and puts his arms around me and rests his chin on the top of my head.

He has a new haircut and new work shirt (with PERDITION embroidered on the pocket). He seems so comfortable with my friends. They’re clearly dazzled by him.

We say goodnight and walk to my car. He puts his bike in my trunk so I can drive him home. Then he tells me everything he noticed about my friends and other people in the bar. Like Ma would say: “He don’t miss a trick.” I ask him about Mother’s Day.

“Will you see your mother this year?”

“No, she’s messed up.”

We’re quiet as we drive down San Pablo.

“You know,” he says, “I’d really like to get her out of the ghetto for a day. Take her for a drive.”

“Where would you take her?”

“Maybe to Vallejo. I hear they do Civil War battle reenactments there. I think it would do her good to see white people killing white people.”

Marcus has been giving me piles of old photographs he finds in dumpsters — hundreds of snapshots and formal portraits of Black people — strangers. I don’t know what to do with them. This week I read an article by Teju Cole about found photos. “I had the sense that my possession of these pictures was not their ideal posterity.” Me too. But now these things are my responsibility.

June 27: Marcus came over for birthday dinner and cake in the front parlor and then we watched YouTube videos (O.J.’s 1970s Hertz commercials, which Marcus had never seen, and “Blackberry Molasses,” a song he had told me he liked when he was little). Suddenly, from the window we heard Rosa on the landing reprimanding Sonia, the most strong-willed toddler I have ever known. Sonia’s furiously angry about the birth of her baby sister. I hear her screaming about it every morning. Rosa’s tone was controlled and gentle, as always, but her voice was shaking. We went downstairs to see what was going on.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I told Sonia she had to take her bath and before I knew it, she ran down the stairs and up the street.”

Sonia was keeping an eye on me and Marcus and trying not to smile. Rosa was trying not to cry.

“There are cars and trucks in the street, Sonia,” Rosa said. “The street can be so dangerous…”

She choked back a sob.

Marcus leaned forward and smiled conspiratorially at Sonia. He raised his hand to give her a high five. She wiped her eyes and smiled at me. I nodded.

She slapped his palm.

“Good job,” he said. “How far did you get?”

****

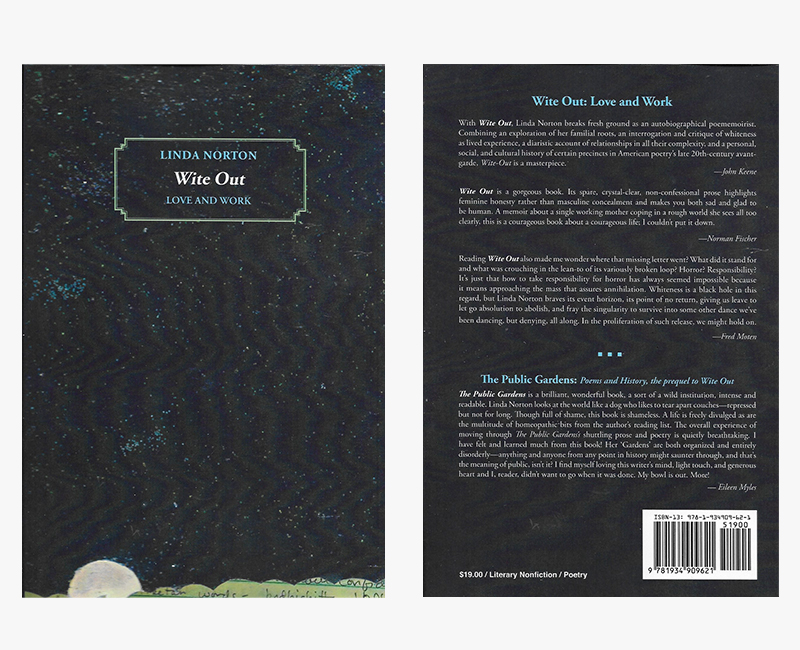

Thank you to Claudia La Rocco, Gordon Faylor, and Suzanne Stein for my time in this space, Open Space. If you have enjoyed my five posts on this site, you may like my new book, Wite Out: Love and Work, (available now in advance of official publication date) and my old book, its prequel, The Public Gardens: Poems and History. You can order directly from the marvelous people at Small Press Distribution, or, eventually, from the online behemoth and bookstores taking online orders. Like every other author of a new book right now, I’ve cancelled all my new-book IRL gigs in Oakland, New York, and Boston. Maybe we’ll reschedule someday. See you when I see you! Stay safe. Love, Linda