JOKER and Its Discontents

There’s a major work of contemporary Hollywood cinema I’ve seen bandied about here and there conjoined to the epithet, “boring.” This seems almost a code word, because when examined, it comes out the film is anything but boring, but deals with issues, and with a character, that some people haven’t any time for.

Narrative cinema is theater in which to immerse our psyches. Presumably viewings occasion opportunities to empathize with, and even identify with, all manner of people, beyond bounds of ethnicity, sex, age, class, etc. Beyond even bounds of ideology or political affiliation. Here we can imaginatively enter psychic states of being hopefully far from our own: alienation, trauma, madness. Perhaps we suffer from some versions of these, and see a part of ourselves up there on the screen. A good experience at the cinema often entails going to some version of human hell and back, from which we emerge in some manner of catharsis, a process sometimes lasting for hours, even days, after being struck to the core.

A hallmark of the American liberalism I grew up with in the 70s was human understanding. Juvenile delinquents, criminals, even psychopaths, were understood to be products of a corrupting society. This was a legacy that went back how far? Rousseau? Without having examined it in depth, my belief is these ideas were ramped up a bit passing through the sieve of Freudianism, and the crucible of WWII. Hollywood cinema was to a large extent a cultural expression of this sensibility, and criminals were often shown as oppressed fighters for liberty, or just survival, within a social morass of indifference alternating with malevolence and conformism. Hence You Only Live Once in the 30s, They Live By Night in the 40s, and Bonnie and Clyde in the 60s. The psychopath could be a figure to empathize with, at least to some degree: Hollywood filmmakers were especially empathetic to the female psychopath: Leave Her to Heaven, Out of the Past, Gun Crazy, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? What is seen as an archaic and oppressive idea now, the inability of the male to know the female, and to understand female experience (which, despite its unfashionability, is still and always an element of male experience), factored in these films as expressions of liberal tolerance: what couldn’t be known couldn’t be judged, and must therefore be tolerated, even empathized with, at least on some level. Leave her to heaven to judge.

As everybody knows, liberalism, and the left generally, have more recently been subsumed within a fury of identity politics, and it’s right for the term “liberalism” to be dispensed with for the more accurate “progressivism,” because the underlying logic is one of human perfectibility. We are all capable of being formed into better creatures, and it’s both our responsibility to do so on our own, or with friendly (or not) prompting by others, and our fault for failing this imperative and exterior measure. (This isn’t far off from the logic of old school right-wing Bible-thumpery.) Since the lottery of reproduction and genetics has us born as members of classes either given social sanction or not, we are born more good or bad, and are more or less worthy of empathy and scorn on the basis of the various identities we are born into, actual experience and contaminating familial/social conditions be damned. Contemporary progressivism has flipped the old school liberal script. Fair enough, I guess, if this were a zero-sum game, but like it or not, we’re all in this big social boat together, and this constant castigation of deplorables—something I do under my breath all the time myself—isn’t working out so well. It may actually contribute to making the planet unfit for human habitation.

Arthur Fleck joins the pantheon of cinema psychos with whom to identify and meditate on. I trust I’ll never chase my family around a hotel with a baseball bat, but I can feel myself in all of Jack Torrance’s many failures, and even some of his delusions. I don’t identify with Travis Bickle’s racism, but I do with his sense of being an alienated outsider adrift in a cityscape populated by hostile others. I don’t identify with all of Jake LaMotta’s various psychoses, but I do with his attempt to reclaim a sense of self that’s been wrested away, often by his own appendages. I don’t imagine I’d ever murder a young woman in cold blood, and yet I’ve been up that river with Captain Willard more times than I can count. In the creation and sustaining of a private world in response to trauma, yeah, I’m even a little bit Norman Bates. There’s currently a doctrine of the necessity of “likeable,” “relatable” characters for movies, and I love lots of these from times past, so I’m not against them in theory. But I don’t go to art for programmatic indoctrination/affirmation. I go to it for psychic experience, perhaps even a little soul healing. It helps in this to sometimes have brushes with madness, and always for screen characters to be some manner of authentic human, be it the minimalist morose meditator, Jeanne Dielman, or all the many maximalist goofballs of Jerry Lewis. Because they are human, it will always be time for psychos. They’ll always be relevant, because madness will always be with us. The psycho will not be cancelled.

I saw the trailer for Joker repeatedly before 70mm presentations of Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood. I didn’t especially like this trailer, but some of the images seemed compelling and tense, so when excoriators told me I shouldn’t see it, I made a point to. What confronted me was at least somewhat astonishing: a Dostoyevskian descent into madness from an unreliable perspective in the loose trappings of a modern comic book movie. I’d never seen one of these, or anything by Todd Phillips, before. I wasn’t sure contemporary cinema could do this kind of thing. I’d later come across carpers harping on how Joker was “boring” in part for its supposed derivativeness — but is there art that isn’t in some sense derivative, art that has no model? One of these naysayers presents himself as the big De Palma champion—nothing against De Palma, but jeez. Phillips might have learned from Peter Bogdanovich’s experience during the release of What’s Up, Doc?, which he tried to situate for reviewers by comparing to Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby. Bogdanovich was of course consequently skewered for his film’s supposed lack of originality, though it had plenty of this to spare provided by his own personal sensibility, including its various designed connections to the history of cinema comedy.

Among other things, what I saw in Joker (viewed in 70mm) was, rather, a dense network of allusion, both to other artworks, and to tensions and events within history, often for the point of contemporary social critique. Arthur’s first bout of murderousness, for example, reworks the Bernie Goetz subway shootings to make the victims affluent creeps, one of whom harasses Arthur with his rendition of “Send In the Clowns.” Sondheim’s original involved self-mockery/auto-critique by members of the upper class. Phillips’ creep ignores, or is ignorant of, this original intent, and repurposes the song for abuse. How many of these types have we seen in recent times, propelled by class and connections from their suburban or midwestern native environs, now terrorizing our urban streets with their bullying banality?

Frank Sinatra’s pop hit version of “Send In the Clowns” is heard during Joker’s end credits, and another Sinatra hit, “That’s Life,” provides the film’s ethos: the feeling of life as comedy, but jazzed up with bitter ironies and the grandiosity so native to Sinatra. The perspective of the song is that of a streetwise theatrical man, a troubadour or clown, who’s seen the world and all its pain from a vantage of multiple, shifting personae. Arthur Fleck, who goes from sweet victim of hearth and streets, to a raging, supreme dispenser of misconceived vengeance, couldn’t find a more apt anthem. Other songs used in the film, however, add additional layers of irony: the Charlie Chaplin-composed “Smile” alludes to the universally celebrated clown and his charmingly humble, bumbling-yet-graceful man-on-the-streets persona, but also to further complexities: Chaplin was a controlling genius filmmaker of the greatest success and renown. A master of illusion and personae creation, he also played a psychopathic murderer in his own Monsieur Verdoux, and suffered the fallout of his left-wing politics coming under attack in the McCarthy era. Joker will similarly master the creation of his own persona and myth, not to mention serial murder, and Joker itself will come under fire for its out-of-fashion, “irrelevant” sensibility. When Arthur’s ready to present himself as Joker to the world, he performs a dance poised somewhere between awkward and balletic down a flight of stone steps outside his apartment building to the tune (presumably heard inside his head) of Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll Part 2.” The stone steps are visually reminiscent of the flight seen repeatedly in The Exorcist (a major work, and key shockfest of the early 70s), which are made dramatic use of in that film’s dénouement when Father Karras goads the demon possessing Regan to enter his body, whereupon he plunges out the bedroom window and down the steep staircase, to his doom. Joker, reconciled to his inner demon, lands safely. Glitter’s song is a more contemporary evocation of the demonic: the imprisoned Glitter has a long history as a serial pedophile. The song has its own long history as rallying intro music in American sports arenas: are we, Joker’s audience, ready for this impending confrontation with evil, evil that has, at least covertly, already been part of our lives, and in some manner, because it is, unfortunately, innately human, always will be?

Besides the films used as models prattled about online, Joker deploys many other homages and allusions: the sequence, for example, from Chaplin’s Modern Times (the film for which “Smile” was composed) watched in a patrician-packed upscale vintage theater. Hobo Charlie, set loose in an empty department store late at night, repeatedly roller-skates close to the naked edge of a missing railing, from which he could plunge several stories. Ah, what hilarity for the penguin-suited. At Joker’s close, Arthur has a confrontation with a woman who’s perhaps his lawyer, riffing on dénouements involving various loved and/or coveted female figures in Crime and Punishment, and two films derived from Dostoyevsky’s novel, Pickpocket and American Gigolo. Paul Schrader, Gigolo’s writer-director, was also the screenwriter of another film influenced by Pickpocket, one of Joker’s primary models, Taxi Driver, which also ends with a similar sequence. Like all these films, Joker takes its title from a role, a profession a man takes on like a persona, using it to provide meaning and form for an otherwise empty existence. Unlike these films or the Dostoyevsky, Joker’s final human exchange doesn’t end well for the lawyer. This last seems reflective of Joker‘s simultaneous boldness and subtlety in addressing difficult matters: Arthur’s ostensible lawyer is the last of several black women populating Phillips’ film. Aside from Arthur’s very problematic mother, almost all of Joker‘s female speaking parts are cast with black women, most notably by Zazie Beetz as Sophie, Arthur’s neighbor and love interest, a key figure portrayed with great sympathy. Another major black female character is Arthur’s social worker, seen only in the first third of the film, but who nonetheless exerts a psychic gravitational pull as Arthur’s mental health professional, whom he seems to identify primarily as a bureaucrat, but who maintains a concerned, if constrained, watch over him. Although, as she announces, the funding of the program providing care for Arthur is cut, and she therefore disappears, Arthur’s ostensible lawyer at Joker‘s end is roughly an analogous figure: a slightly older black woman in the tenuous position of having to observe and provide care for a slightly younger white man who’s developed full-on psychopathy. Do these women bear witness to the products of American madness that has long been arrayed against them, and presumably will continue to be? While Phillips’ film is by no means the confrontational work in regards to race, a degree of appropriate attention is paid to powder keg urban environments, with working and under class social segments of various races set amongst each other in a stew of mutually-assured resentment. The brown boys knocking the clown-clad Arthur on his ass at Joker‘s start set the film’s stage, and although analogous figures won’t return, and although Arthur himself evinces no sign of racial animus, via its beginning, the bitter, yet all-too-authentic taste of such conflict is baked in Joker‘s cake. The film’s racial politics may be no more than an acknowledgment of the existence of such, and given this work’s grounding in universalized American myth, and overarching focus on class and the divide between the USA’s multitudinous have-nots, and its minuscule, yet powerful number of haves, this is arguably justified. At any rate, there is at least a semi-covert, yet potent, conflation of black female social worker and lawyer: they coalesce as figures of concerned rationality with whom Arthur exists in tension, and needs to overcome. Another strand of Joker‘s complex web of intertextuality may be its dénouement, which possibly reworks Cammell and Roeg’s Performance, a masterpiece also climaxing with a mysterious murder of a figure with whom its protagonist has been engaged in a similarly cryptic confrontation.

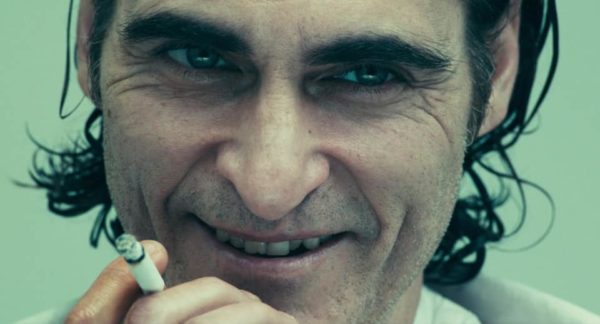

Whether a reference to Performance is intended and/or conscious or not, Mick Jagger’s key line in that film fits Joker like a tailored calfskin glove: “The only performance that makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.” Joker fits the being conjured by Joaquin Phoenix much like the unexpected elegance of the finally fully-realized Joker’s suit. In this era of manic, contrived performance calculation, Phoenix achieves, or certainly embodies, madness. This preternaturally bravura performance has strangely been used as a cudgel against the film he stars in, as well as Phillips, the man who guided him in his way. Actors apparently create and inhabit their roles in a vacuum, they merely need technicians to turn on cameras, and go away. But, yes, Virginia, Joker does have a co-writer/director, as every frame and cut of Joker’s at least somewhat exquisite découpage attests. This film, an amalgam of period piece, fantasy genre exercise, gothic neo-noir, biopic, action/adventure, musical-comedy and serial killer genres, would’ve been the stuff a future cult was made of, if not for the embarrassing reality of its fortunate box-office reception. As a punk kid dweller of the Taxi Driver-era 1970s NYC, I can attest that Joker got Gotham right, it’s almost uncanny. At the very least, mounting this work required vast amounts of commitment, talent and skill. Those wedded to their prejudices will refuse to see the evidence onscreen, or accept what comes via their eardrums, but the fact is a filmmaker largely known for commercial comedies (which I haven’t seen, so I’m currently accepting this description on faith) had it in him to make a major visionary work of genre cinema. The doubters refuse to accept, or even mock, Phillips’ background in documentary and underground film. With my own commitment to celluloid, my friends and associates are perhaps surprised to find me championing this digitally-lensed work. But it was released in both 35 and 70mm film prints, and Phillips has described himself as a man of celluloid film. His previous efforts, including those commercial comedies, were shot in film, and he intended to shoot Joker in 65mm, only arriving at the digital 65mm analogue when Warners refused him real deal 65mm. Whatever the shooting format, the atmosphere Joker evokes is that of the era in which it’s set, with its all-too-human feeling, pre-Giuliani soot and grime-swathed NYC/Gotham. Phillips has described how he set out to make a work with the feel of a “handmade film,” and he’s somehow jam-packed as much handcraft and humanness into it as a comic book movie could possibly allow. The aforementioned opening sequence, in which a clown-suited Arthur Fleck flack-dances on a busy Gotham street for the sake of a going-out-of-business musical instrument emporium, only to be brutally brought to the concrete by a gang of juvenile ne’er-do-wells, could only have been created by someone who’d walked those boulevards. I walked them, too, so I know. The dense atmosphere of this work has just the whiff of the time tunnel, whisking us back to longed-for dinginess and sleaze. Phillips’ Gotham mixes many authentic touches with inventive, forays of the imagination: porn theater marquees, equipped with fully-fleshed titles tailor-made for Joker’s universe, add to the stew. It took one not quite immersed in all things Batman time to sort things out, however. Inquiries made, for example, had me finding out that the lurid “Ace In the Hole” porn movie marquee was no arbitrary touch—the Joker from back in his comic book glory days regularly mockingly referred to having an “ace in the hole,” which would no doubt turn the tables on Batman, while doing card tricks, and the like. That Phillips disassociates the tagline from Joker directly, and instead has it hovering around in the background as part of the “origin atmosphere” that Arthur is himself absorbing—this is the move of an artist.

An issue even some fans of Joker have complained about is its genre trappings. Wouldn’t it be a stronger film if it had no connection to silly clown costumes, or future wearers of capes and pointy eared-masks? As something of a fan in my childhood of the limited number of Batman comics I had access to, as well as the camped-out 60s TV show, which I must have imbibed at least a time or two, I’m not quite the neutral observer. This stuff has at least the ghost of resonance for me of myths one’s been exposed to from practically the cradle. Still, none of the feature films from the 80s on lured. Perhaps this renders me the perfect judge? All I can say is, although this work is as grounded in social and psychological realities as one could imagine any work of fantasy possibly being, it’s plenty resonant on the ultimate plane, the mythic. Layers of meaning and feeling fly every which way when Arthur seeks to meet the man he believes to be his father. There are those who would dismiss the value of myths derived from comic books, but myths that resonate within a culture are those that, for whatever the many reasons, and no matter where these myths originate, hit home on both individual and collective psychic buttons. As with fairy tales, any of which may be more or less resonant with any one of us, the mythic strains in comic books resound for many on the most potent level, the level of our childhood selves, which are part of us, no matter how buried and suppressed, until our last breaths. The meat of meaning is found here, if often only on the level on which the hero/villain dichotomy/clash reverberates.

That Joker at least loosely adheres to the Batman/Joker mythos allows it to make profound moves at least semi-sanctioned by the original big boy of theater theory: that old Greek fellow, Aristotle. In the Poetics, Aristotle describes two of the supreme techniques of Greek Tragedy: peripeteia, which Merriam-Webster describes as “a sudden or unexpected reversal of circumstances,” and anagnorisis: recognition, or, as defined by Aristotle, “a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune.” While it would be a stretch to say Joker makes use of these techniques precisely as described by Aristotle, Phillips’ film nonetheless deploys a version of them suited to dark tragicomic cinema: not quite midway through Joker, Arthur begins a quest to learn his true origins, hoping to connect with a father he’s never known, or even been told the identity of until now. This finds him making a series of progressively traumatic discoveries about his mother, none of which receive ultimate verification, and attempting to meet the man his mother has inadvertently given the paternal imprimatur: Thomas Wayne, father of young Bruce.

At first, Arthur will only be able to cross paths with the boy he believes to be his half-brother, and then only through the bars of a solid iron fence. You know me by now, reader, you know I’m no true Batman or Joker cultist; nonetheless, in my viewings of Joker thus far, these moments have had me awash in the frissons I’d imagine the elite of the Greek polis experienced while witnessing the first performance of Aeschylus’s The Libation Bearers, and its recognition (anagnorisis) scene of brother and sister Orestes and Electra, reuniting after so long they can’t recognize each other, and Electra only able to finally identify her brother via talismans. Maybe these types of resonance-laden recognition scenes are common in the modern “origin story”? Of course I wouldn’t know, but surely there can be few delicate, tender moments in these as when little Bruce slides down a pole connected to his play structure, of such a childish stature as to be barely off the ground. Yes, for those of us who grew up watching Adam West and Burt Ward manfully sliding down those giant fire poles in their tights, this is an emotion-laden sight. Almost all narrative partakes of Aristotle’s dramatic precepts, of course, but Joker taking part within a greater mythic superstructure allows the tiniest moments to resound almost operatically. While many of these operate in the traditional theatrical manner, with onscreen characters making their discoveries, experiencing the emotional fallouts from peripeteia and anagnorisis, others—the most profound ones for cinema audiences—exist only for viewers: as we come to recognize the tender boy onscreen as young Bruce Wayne, we experience the revelation that this is the future Batman (of which both Bruce and Arthur can have no idea at this point), and that we are witnessing the first meeting of Batman and Joker, the commencement of a cosmic cycle echoing back at least as far as the ancient Zoroastrians, and the semi-eternal battle of Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. After Arthur dispatches the three Wall Street thugs on the subway, he recovers in a dingy abandoned public restroom, finding himself again in the making of tentative, graceful/awkward tai chi/chi gung dance moves. Over the course of time, we have scene upon scene of revelations that these alternating modes of murderous revenge rampage, soulful expression, and nihilistic trickster are all human elements conjoined in the apotheosis of this mythic figure, the Joker. Such profound moments are part and parcel of the gift of cinema, a new mode of catharsis modern times have brought us, rendering our emotional processing all the more collective, and simultaneously powerfully individual. Much of Joker’s power is a product of how Phillips has managed to coalesce and synthesize all manner and modes of art, high and low. A comic book villain is given the Dostoyevskian depths of the Paul Schrader “man in a room” existential despair treatment. A clown becomes star and savior for a discarded populace that finds itself in a spiritual and economic wasteland. Will Joker’s potent, dark populism somehow provide guidance to the means of deliverance for its day? That Joker has such concerns is indicated by the Excalibur poster seen outside a movie theater: John Boorman’s film is the supreme rendering in the English-language cinema of the Arthurian myths, and their themes of personal, collective, and national struggle for harmony and fruition. Joker’s Arthur, similar to Boorman’s, begins as a man-boy, and over the course of his film develops a means of collective deliverance. This malign sovereign, Arthur Fleck, however, assumes an inheritance not from royalty, but from the existential imperative of one coming to consciousness of his inner value and social worthlessness: a “fleck,” after all, is defined as “a speck; a small bit,” as in “a fleck of dirt.” It’s also “a spot or small patch of light, etc., and “a spot or mark on the skin, as a freckle.” But “fleck” is also a verb: “to mark with a fleck or flecks; spot; dapple.” Consequent to the murder he commits before descending that staircase and assuming his Joker throne (similar to another, who began with a descent down an escalator), Arthur Fleck renders himself flecked, dappled with the blood of his victim. Similar to Napoleon’s act of auto-crowning, Joker anoints himself.

I write this on the evening of the concluding third day of the Democrats’ opening presentations of the impeachment trial of a seductive joker, but one far-less-so to me than Joker’s Joker, Donald Trump. Reportedly, Republican Senators are “bored,” they’ve heard the details of abuse of power, treason, and general infamy all before, and they want to get on with their acquittal. The sooner they do it, the less likely the information-challenged will notice their duplicity, and the country will be able to unconsciously embrace full-on corruption. This can’t help but be resonant when I come across all these declarations of how “boring” Joker is. Oh, yes, this tale of woe and murder, class conflict and ecstatic madness, mythic resonance and of a place, time, and atmosphere now sadly lost on the river of no return—yes, oh, so boring. Even Joaquin’s superlative performance, so sad to have this screen time wasted, time for a nap.

What’s going on here? As a Jungian, I see in C.G. Jung’s psychology a far more complete and humane picture of what it means to be human than anything mapped out in the postmodern wastelands. The sense of male and female not being discrete entities–that in the psyche of every male there’s a female, and vice versa—perhaps this is all one needs to know to become interested in the fact that for over a hundred years, there’s been a psychology more complex and attuned to the minutiae and passions of human reality than anything dreamed of by the “theory” peddlers. These have ultimately had some of us thinking there are some types of humans more valuable than others. Those valued by American society in previous times are now appropriately struck low. On my local public radio station, I regularly hear about how people of a certain ethnicity, sex, and age are no longer “relevant.” Of course, this is just a microcosm, the natural fractures within American society are only being heightened in this current climate, fostered, no doubt, by that joker Putin’s minions. There would be major segments of society that would take me on the basis of ostensible identities, no doubt. I don’t crave acceptance by these. The basis of American society at its best has been both one of elective affinities regarding creed, and openness to the creeds of others. Pluralism was this heyday’s watchword. At any rate, I’m a man from a multi-racial, multi-cultural family, and resent attempts by those who would pigeonhole me.

I essay all this because I intuit the rejection of Joker by some is part and parcel of not just a fracturing of society, but a fracturing of man from him and herself. Box office returns have us know that many have taken a variety of pleasures in Phillips’ work, and/or solace from its acknowledgement of the mental health issues plaguing modern American society. But Joker does much more than acknowledge these issues, it’s a work very much from the perspective of one suffering from them. It’s an inside portrait even more than Taxi Driver, in that really nothing is shown outside Arthur Fleck’s evolving perspectives, and the sympathy shown to him by the film is more embracing than that of Taxi Driver for Travis Bickle. We see moments, elements of kindness by people, alternating with the reverse, then more and more malign behavior until Arthur suffers a complete psychotic breakdown. All this would be all-but-completely nihilistic, but for the fact of Fleck’s own good intentions, and his occasional (and sometimes delusional) perceptions of good intentions on the part of others. If we can see through his eyes and accept the totality of what we see, we are given a vision of a world partially good, but mostly evil. We can identify with someone who’s suffered many of the worst woes of the world. And identification with someone of this sort in an imaginatively reinvented world, at least emotionally, couldn’t provide more of the opportunity for psychic healing a work of art should occasion, especially in the current climate. The film is a giant clot of everything contemporary society represses: the value and rights of the working and under classes, as well as outsiders, on the part of the right, and the full complexity of human nature (and even that there is human nature) on the part of the left, which believes humans can be conditioned into being their idea of good (or, if not, then just “cancelled”). Joker is a fully-fleshed embodiment of what Jung called the “shadow,” which constitutes everything we repress, good or bad. Those of us suffering monotheistic culture desperately want to be good, but we’ll never rid ourselves of our own evil. Phillips’ film is a complex work, and rather than just a social portrait, is also a therapeutic/aesthetic tool with the potential to make people just a little more whole, and consequently more connected to their fellow humans.

“Boring”? Yeah, no. Like those senators who’d prefer to avoid their responsibility for Trump’s criminality, some viewers are perhaps loathe to bring to surface all of Joker’s many implications, for they, like their fellow humans, are implicated themselves. It’s an understandably reflexive, defensive move, humans sweeping their own complexity from view. But doing this with our latent psychoses and potential fascisms for the sake of our increasingly rarefied self-images doesn’t pay. And, as another Arthur, Arthur Miller, a man of a generation which both witnessed and participated in the worst of recorded human history, wrote of a socially discarded, but yet not-fashionably-discarded-enough Salesman from his imagination: “Attention must be paid.” If this doesn’t happen, then so much the worse for all of us.

Comments (2)

Since you have some experiences as a writer, I’m surprised you didn’t see that your naive and poorly thought out takes on contemporary race politics added nothing to the article. The two random interjections had no relation to the movie and added no insight, just made it look like you have apersonal bugaboo that you don’t deal with competently.

Great piece. Nice to find you again, Brecht. It’s been a long time.