Homeland security: facial recognition in machines and crows

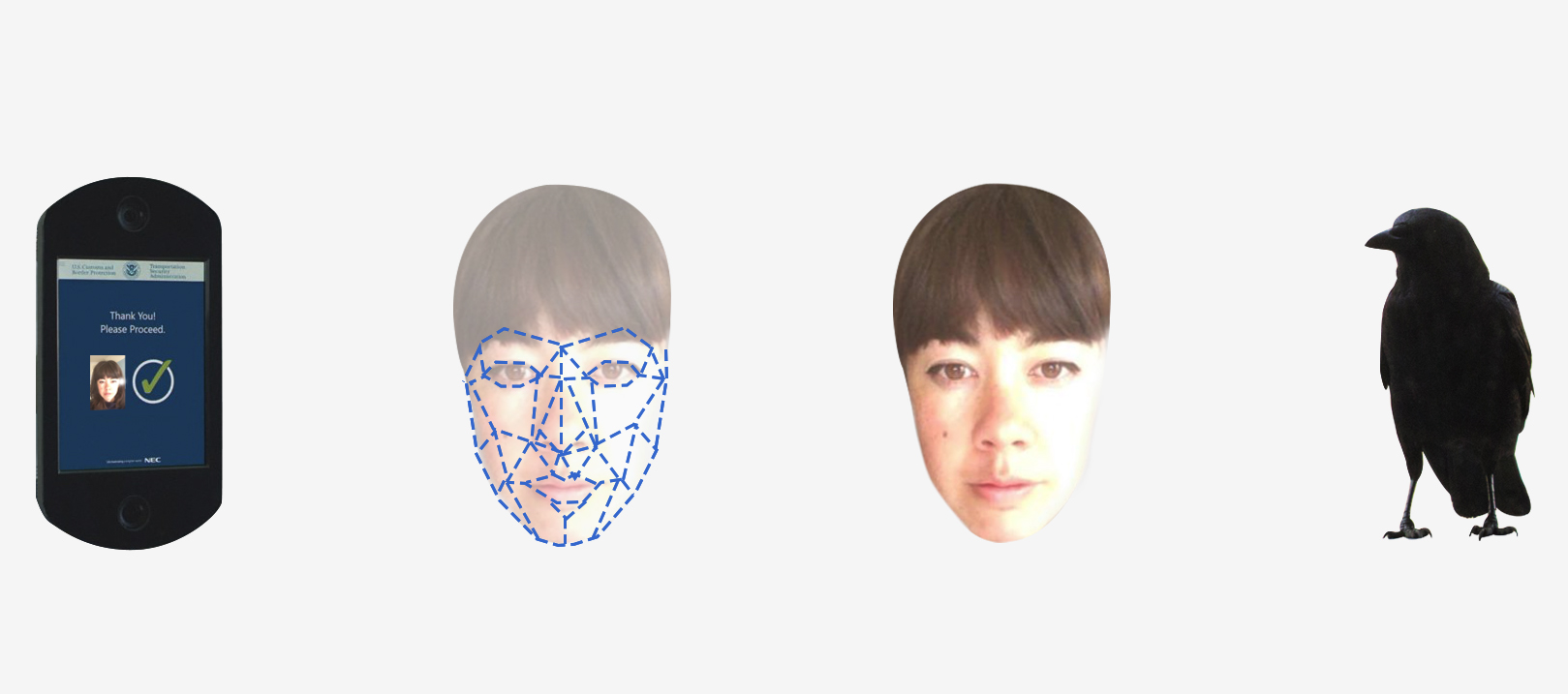

Last October, I found myself at the Atlanta airport on the way out of the country for a conference. A Delta employee at the gate announced with surprising nonchalance that today they would be using facial recognition for the boarding process; she motioned toward an eye-level, oddly rounded screen atop of a gray plastic base. It looked more like something from a doctor’s office than an episode of Black Mirror. Next to it, a Delta sign read “ONE LOOK AND YOU’RE ON,” which, like the airline employee’s cheerful tone, framed this experience as a newfangled convenience.

Though no one protested, I sensed a familiar feeling in the air: that of a tired assent to some new, confusing, and vaguely dystopian terms. We lined up dutifully, following the instructions: “Please stand on the circle and look at the camera.” As my picture was being taken, I wondered what it was checking it against. Oh right, my passport photo is part of a Department of Homeland Security database. Then I became worried. In my passport photo, my hair is unusually big, I’m not wearing glasses, and personally, I think my eyes look weird. I wonder if — BEEP. A friendly checkmark appeared. Deep in the guts of some system, some measurements had matched some other measurements, and I had been deemed satisfactorily me.

It wasn’t my only time being recognized by a nonhuman entity. Starting in 2017, it was possible for Facebook to find me in photos even when no one had tagged me in them. There was the time I worked on a project that required me to enter a data center and thus have my eyes scanned — to which the machine responded flatly, “Your identity… has been recorded.” But starting in 2016, my identity has also been recorded by something, or someone else: crows.

That was the year I read about John Marzluff, the go-to researcher for all things crow-related. He’d noticed that crows on the University of Washington campus would hold grudges against humans who had caught them for studies, so he had his researchers go about their business — but with novelty Dick Cheney masks on. Sure enough, the crows thereafter mobbed anyone wearing the Cheney mask. Not only did it work if even the mask was upside down, but the crows appeared to transmit this information, so that the Cheneys acquired more and more haters. This made me wonder (with some delight) whether Marzluff’s plan was actually to make sure that crows would attack the real Dick Cheney if he ever dared to visit the University of Washington. But it also made me wonder whether I could get the neighborhood crows to recognize my face.

how to befriend a crow

My balcony, being one of many on the dark side of an apartment building, was not an intuitively interesting place for the neighborhood crows. It took a few months of leaving peanuts on the railing to get their attention, but eventually a family of three or four crows became regulars, arriving around the same time each day and forming a neat line on the telephone lines closest to the balcony.

crow-veillance

Once this mutual habit of ours had formed, I would watch the crows and their peculiar habits — yawning, scooting up to one another hoping to get groomed, or pecking at a grotesque complex of mushrooms in the neighbor’s front yard. But I also hoped that I was being watched. Sitting on the balcony felt like hitting “record” on a mysterious device, since every minute that they peered over at me, I entreated them silently: Record this face!

My experiment soon yielded results. Sometimes if the crows were still on the wires when I left for the day, they’d spot me at the building entrance and follow me around the corner, gliding down the street and landing on telephone lines right over my head. Or they might land on the sidewalk and waddle behind me for an entire block. One time they followed me to the nearby bus stop and watched, perhaps puzzled, as I got onto a bus. These days, I’ll be walking near my apartment and they’ll glide down suddenly out of nowhere, landing right in front of me. Whenever I return from a long trip I wait on the balcony for them; they’ll swoop by especially close to my face, perhaps in greeting or to check that it’s really me.

my sometime-entourage

Animals and machines obviously use different mechanisms for recognizing faces. When my face was captured at the Atlanta airport, “recognition” had to do with a pattern of points around my eyes, nose, and mouth. In general, this means that face detection and recognition make certain demands of the image. Apple’s Face ID, for example, doesn’t work if your eyes are closed, and cameras that scan a crowd for faces have difficulty with faces tilted away.

By contrast, the crows have recognized me on the street when I’ve worn giant sunglasses or have bangs in my eyes, and even during the Camp Fire in November, when I wore an N95 mask that covered my mouth and nose. The crows’ image of me is rarely head-on, since they often spot me on the ground from the top of a tree, or on my balcony as they’re strolling along the sidewalk. I don’t know how they do this. The closest thing I could find to an answer was a 2017 study on macaques’ ability to recognize human faces, in which researchers at the California Institute of Technology identified groups of specialized “face cells” that together could encode a full fifty different aspects of a face. The aspects were things like distance between the eyes, face shape, and skin texture. I wonder whether the crows have memorized so many aspects of my face that even if they’re missing a few, they still know it’s me.

“are you home?”

Technical aspects aside, the biggest difference between facial recognition in machines and in crows has to do with the ends of recognition, and thus how it feels to be recognized. Back at the Atlanta airport, I’d found the Delta employee’s upbeat tone to be farcical given the inherent creepiness of facial recognition and how readily it’s weaponized. In 2016, a new Russian app called FindFace gave users the ability to take a photo of someone and find them on a popular Russian social network with 70 percent reliability — something a Guardian headline speculated “may bring an end to public anonymity.” In 2017, the Dubai International Airport unveiled plans for a tunnel-shaped “virtual aquarium” whose virtual fish would encourage passengers to look around while eighty different cameras scanned their faces and irises. In 2018, the Chinese police used facial recognition to pinpoint a man amid a crowd of sixty thousand people at a concert.

But just as terrifying as a world without public anonymity is the idea of a world where we are not recognized at all. Anonymity, distance, and abstraction are hallmarks of contemporary existence, the cold night in which clusters of friends, family, lovers, acquaintances, pets, and not-quite-pets glow ever more vitally. To be recognized by a friend — instantly, even after years apart — is not just a wonder of neuroscience. It is evidence of a bond, a sometimes miraculous moment in which we are plucked out from the crowd and rendered more than a stranger. The airport is precisely the type of place where I find it most comforting to think back to my crows, and to that “database” in which they have encoded features of my face so specific and delicate that perhaps even I have not noticed them.

a familial fellow

In one of his lectures, Alan Watts said that the body doesn’t contain the soul, but rather the soul contains the body, since the soul for him was “the entire complex of relationships in whose context this organism exists.” To think of people and animals who recognize my face is a reminder that my image exists outside of me and dispersed in the minds of others. I like to think about the difference between this kind of image and a cold series of measurements. The Department of Homeland Security keeps a copy of my face, but it is the frozen face of a stranger, “recognized” by people and machines I will never see and am nonetheless asked to trust. By contrast, the version of my face that lives in the crows is born out of years of mutual attention — attention that binds me to them, to my memory, and to my neighborhood. In that sense, the crows offer a very different kind of “homeland security.”