Yelping Oakland’s Past

From Sand By The Ton, the grand opening and fundraiser for The Big Art Studios at American Steel, 2009. Photo: Scott Beale / Laughing Squid. License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

A few months ago, on the day of Alameda County’s local elections, a friend’s Facebook post caught my attention: “You know, just going to vote in the living room of the ex-brothel, ex-underground party spot that just happens to be my polling place.” The post linked to a sparse Facebook page for a defunct “clubhouse” known as Bordello. The building’s last party was few years ago, and now it’s just a place where people live and — apparently — vote. I’m always sniffing around for stories to feature on my local history podcast, East Bay Yesterday, and this property’s history as a den of debauchery tickled my curiosity.

Judging by the comments responding to my friend’s post (“I was part of a crew that produced Louisiana-flavored shows [called] The Grand Alligator Ball there around 1980”), this was a rabbit hole worth exploring. I started my quest in the most obvious place: Google. Since this was an unlicensed party venue, I was surprised that the top search result for “Oakland bordello” was a Yelp review. A disclaimer at the top of the screen warned that “Yelpers report this location has closed,” but all the user-submitted reviews of the “music venue” were still on the page, little digital memories encased in internet amber.

The top one was a five-star gusher: “I *loved* that space. I called it the ‘Bohemian Fun-house.’ I’ve never seen anything like it and probably never will.” Another five-star review offered this playful impression: “Winchester Mystery House with a carnival twist.” I’d never visited Bordello, but reading this description transported me back to the many Oakland party spots I stumbled through during my twenties and early thirties: “Cheap beers and cocktails, several small stages, magic brownies sitting out on the bar, and a hundred small hidden rooms, passageways, closets, and rooftops to get conveniently lost in.”

Not everybody was impressed with the Bordello’s quirky interior: “Fire trap if there ever was one… scary as a 3rd world airline. I am glad it closed before people died.” One star. My nostalgic train of thought was derailed.

Although Oakland’s underground party scene had been dwindling for years (due to redevelopment, rising rents, etc.), the tragic fire at the Ghost Ship warehouse in 2016, where thirty-six people died during a dance party, felt to many like the end of an era. Throughout the ’90s and ’00s, there were few legal venues booking electronic music, hip hop, punk, metal, or noise shows in the East Bay. This void was filled by wild all-nighters thrown by various overlapping subcultures in former industrial spaces — many of which had been vacant since the post-war era, when major employers and white residents fled “The Town” for the suburbs. Boots Riley promoting an Outkast performance in an abandoned office building; Animal Collective playing in a former carpet factory; Burning Man parties that transformed a decommissioned steel plant into a beach by importing (literally) tons of sand — these were the kinds of events you’d never see advertised in the paper. They were simmering all over Oakland.

This era, which spanned roughly two decades, was a golden age for artists, musicians, and activists (who could live cheaply and raise more money from benefit parties at warehouses than bars or clubs). It wasn’t culturally monumental on the scale of, say, Haight-Ashbury in the ’60s, but it was a significant chapter in local history — one that deserves to be remembered not only for the thriving nightlife elements, but for the lessons that can be gained from examining its inspiring but also messy and fraught legacy. After all, this vibrant atmosphere, which brought an influx of young artists and musicians to the city, helped set the stage for the full-blown gentrification that’s spread throughout Oakland since the Great Recession faded.

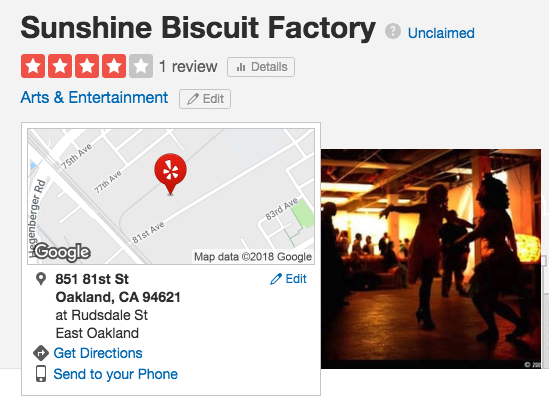

After reading the Bordello Yelp page, I unscientifically compiled a list of dozens of defunct Oakland underground party spots. Some thrived for more than a decade, hosting hundreds of performances ranging from raves to wrestling matches; others only opened their doors for a few rap battles, art installations, or punk shows. Most of these spaces don’t turn up in a Google search, and the digital footprint of the ones that do is tiny (a brief mention in an East Bay Express article about evictions, for example). The only online evidence that a few of these locations ever existed is a single, meager Yelp page.

Even before the post-Ghost Ship crackdown, sharing information online about underground party venues was generally frowned upon (don’t blow up the spot), so there’s a confounding irony in these faux pas surviving as the only bits of accessible information about these spaces. And while Yelp currently does not remove pages of “businesses” that have closed, it’s easy to imagine this policy changing. If it does, a whole slice of Oakland history would fade even further into obscurity.

Besides the precarity of relying on the whims of a corporate website, allowing the history of Oakland’s diverse, freewheeling warehouse scene to be told through Yelp posts is wildly problematic. A common refrain in these reviews is warnings about “sketchy” neighborhoods and “crackheads” lurking down dark streets (to get a sense of the entitled tone commonly found on Yelp, refer to the “3rd world airline” comment above). The overall impression of these micro-narratives is voyeuristic and not particularly insightful; the histories of this era should come from the people who were immersed in it, not tourists who had to leave the party early because “the bathrooms were gross.”

Since many of the buildings associated with this scene have either been demolished or redeveloped, and widespread displacement has scattered its participants, in-person reunions on a large scale are rare. Unsurprisingly, the folks who are still interested in reminiscing and compiling documentation (tapes, video, flyers) tend to gather in closed Facebook groups like “I RAVED in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 90’s.” Occasionally, there is more formal curation. As part of an Oakland Museum exhibition, Eric Arnold’s Hip-Hop Atlas of the Bay compiled photos and short descriptions of notable locations connected with the local rap scene of the ’80s and ’90s. Jack Boulware and Silke Tudor’s book Gimme Something Better gathered oral histories about long-defunct underground punk venues. Events exploring the history and legacy of Burning Man have explored the festival’s long connection with East Bay industrial spaces.

There are benefits to each of these strategies for curating history — and serious drawbacks. The entire contents of a Facebook group, for example, can be deleted by a hacker, a vindictive moderator, or the company itself. And when it comes to books, museum exhibits, and documentary films, decisions about inclusion and exclusion don’t necessarily reflect anything other than the personal preferences of an author or director. The process of curating history — and which elements to enshrine — is inevitably tangled up with all kinds of questions regarding politics and representation.

Crowd-sourcing contributions for some kind of a non-hierarchical, limitless online archive could very well be the best strategy for gathering and preserving information about Oakland’s various underground cultures of the past few decades. Until then, we’re left staring through the fractured, smeared window that is Yelp.

Comments (2)

Hi AV — thanks for sharing the memories. Your mention of the old Liminal space brought back a very vivid image I’d forgotten about. During a rave there, the video projectionist played the slug sex scene from Planet Earth on a giant wall. It was so weirdly engrossing that everybody stopped dancing just to watch the slugs’ intricate mating ritual play out on the big screen!

sugar mountain on san pab, punk live/work that steve (the list) ran till just a couple years ago.

that’s right next door to a place that also had parties, but more DJ EBM type music.

before that, steve ran the same sorta deal on 29th ave and chapman in jingletown. fleshies, federation x, bands like that.

liminal gallery. the *old* liminal. it was in west oakland, kinda by phenomenauts. kitchen sink magazine threw a huge party there round 2005?

i lived at 4001, threw a couple parties myself (they sucked). and the neighbors did too (theirs were better). but preferred parties around the corner at 3920 (or so) san leandro street. saw phantom limbs there once.

3405 piedmont (was that called the fish bowl maybe?) had some bands/parties. saw blast rocks!!! there.

wait. now i think the place on 41st and adeline was called the fish bowl? bah, it’s all fading and meshing together.