The Electrical Scent of Damas: Negritude, The Harlem Renaissance, and The Afrosurreal

Yet above all, the Earth being for me the specificity of Africa, as revealed by Diop, and Jackson, and Van Sertima, and its electrical scent in the writing of Damas. Because of this purview I have never drawn to provincial description, or to quiescent chemistry of condensed domestic horizon

— Will Alexander, My Interior Vita

As a poet, I feel the tension in these lines from Afrosurrealist Will Alexander’s poem, My Interior Vita, from his 2011 collection, Compression & Purity (City Lights). This tension is both a challenge and a declaration residing from the first line, “Above all,” to the last “condensed domestic horizon,” but where does it come from?

It is not the “specificity of Africa,” so much as that line’s distance from “its electrical scent in the writing of Damas.” One must reach across a great chasm of specificity, where scholars like Diop and Van Sertima dwell, to get to the Guyanese artist/poet/statesman Léon-Gontran Damas, and even then, all that is there is his “electrical scent.”

The chasm Alexander addresses is one between the essentialist scholar’s notions of specificity and the more nuanced, nebulous “scent” of Black arts and culture. Regarding Black Radical Imagination and Black speculative manifestations, this tension has made itself known when considering how one should mine the past, present, and future in both scholarly and artistic practice.

As The AfroSurreal Manifesto and Afrofuturism come to the fore in artistic, commercial and academic circles, the struggle between the specific and “the scent” has come with it, posing interesting challenges to both movements. For Afrofuturists, this challenge has been met by inserting Afrocentric elements into its growing pantheon, the intention being to centralize Afrofuturist focus back on the continent of Africa to enhance its specificity. For the Afrosurrealists, the focus has been set at the “here and now” of contemporary Black arts and situations in the Americas, Antilles, and beyond, searching for the nuanced “scent” of those current manifestations. This speaks to a long-standing disconnection between the histories of Black radical artistic movements, exemplified by the supposed chasm between Damas’ Negritude, the Harlem Renaissance, and the contemporary Afrosurreal movement.

What Alexander posits in his poem is what Peter Lambourne Wilson termed in his book Sacred Drift: Essays On The Margins Of Islam (City Lights, 1993) as a “poetic fact”: An insurrectionary image that punctures history, one that both troubles and stimulates, one that asks more questions than it answers. The question I am interested in for this essay is: What is Damas’ “electrical scent,” and how can it inform us about the connected histories of contemporary Black cultural movements?

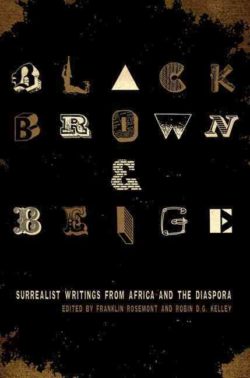

In the seminal AfroSurreal anthology Black, Brown and Beige: Surrealist Writings From Africa And The Diaspora (UT Press, 2009), editor and UCLA historian Robin D.G. Kelley calls Damas a member of “The Triumvirate Of Negritude And L’Etudiant Noir”: “It was this remarkable trio — (Amie) Cesaire, (Leon-Gontran) Damas, and (Leopold) Senghor — who in March 1936 started the paper L’Etudiant Noir, long renowned as one of the monuments of Negritude. Indeed, it was in the pages of L’etudiant Noir that the word ‘Negritude’ (coined by Cesaire) first appeared in print.”

In the seminal AfroSurreal anthology Black, Brown and Beige: Surrealist Writings From Africa And The Diaspora (UT Press, 2009), editor and UCLA historian Robin D.G. Kelley calls Damas a member of “The Triumvirate Of Negritude And L’Etudiant Noir”: “It was this remarkable trio — (Amie) Cesaire, (Leon-Gontran) Damas, and (Leopold) Senghor — who in March 1936 started the paper L’Etudiant Noir, long renowned as one of the monuments of Negritude. Indeed, it was in the pages of L’etudiant Noir that the word ‘Negritude’ (coined by Cesaire) first appeared in print.”

Negritude, being one of the first international Black cultural movements, has been defined in vastly broad ways. Wikipedia includes in its definition, “The problem with assimilation was that one assimilated into a culture that considered African culture to be barbaric and unworthy of being seen as ‘civilized.’ The assimilation into this culture would have been seen as an implicit acceptance of this view.” This commentary would lead one to believe that Afrocentrism and the scholarly specificity of Africa were the driving engines of Negritude, and thus Damas’ “electrical scent.” However, in Black, Brown and Beige, Professor Kelley includes an excerpt from Damas’ 1974 collection, Continuities. 1974, the very year Amiri Baraka coined the term, “Afrosurreal Expressionism:”

Startlingly, the Negritude was not conceived by Africans in the Motherland, but by those influenced by the spirituals, blues and jazz of the United States of America; the sound and dance of Cubans; the batucada, samba, frevo, and capoeira of Brazil; the merengue and petro of Haiti; the mereque of the Dominicans and Puerto Ricans’ the calypso of Trinidad and Jamaica’ the casse-co of Guyana, not to mention the beguine of Martinique and Guadeloupe – all of which had their origins in Africa.

Here Negritude was born — not in Africa, but the West Indies.

It was not until the 1920s and 30s that there arose a generation of writers who, instead of voicing cries of complaint and hope, demanded justice, and of Blackness its entitlement to civil and cultural rights, as W.E.B. Du Boise defended so eloquently.

It was the birth of the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro in whose name Langston Hughes proclaimed a manifesto:

We younger Negro artists who create intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If the white folks seem pleased, we are glad. If not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. Ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, their pleasure doesn’t matter. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know them, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves.

•

The profound sense of this manifesto was realized by Negritude: Cesaire, Maugee, Achille, Gratian, Senghor, Diop, myself and others. We were determined to follow in the footsteps of Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Sterling Brown, and Claude McKay, the author of Banjo, who realized in 1930 (a date to remember), a much-deserved success. Cesaire, Senghor and I helped as much as we could to make all of their works well known.

— Leon-Gontran Damas, Negritude and Surrealism, 1974

In one paragraph, Damas makes the connection between Negritude, unequivocally showing that its impetus is deeply grounded in the contemporary Black American and Antillean cultural production of the Harlem Renaissance, and ends with a prescient declaration to the power of Black American manifestos. This passage, taken as a whole, tells us that Damas’ “electrical scent” is clearly an AfroSurreal one.

As Black speculative practice evolves into the new millennium, it would behoove artists and scholars alike to remember both the ancestor veneration and analytic rigor of those who came before us, and attempt to approach our practices with a “both/and” mentality over an “either/or” one. From Robin D.G. Kelly’s Black Radical Imagination to the Afrosurreal Manifesto, to move away from these terms and functions is to widen the chasm between the specific and the “scent.”

As organizer, Adilifu Nama, said at their Astro-Blackness conference in 2015 (Loyola Marymount University), “I think Afrosurrealism — that is Afro, Afro-American, Afro-Latino — Afro communicates what in fact we are looking for. It gives us an orientation. It locates us in a historical discourse. When we move away from Afrosurrealism, we move away from [Amiri] Baraka [and] notions of Black Dadaism that’s lost in this general notion of Ethnicity. I need to know who is saying what to understand what is being said.“