Faces of War

I was invited by Corinne Silva, coordinator of a National Media Museum project on photography and humanism, to have an exchange with Julian Stallabrass, a London-based critic and curator who has taught at UC Berkeley and is the author of Memory of Fire: Images of War and the War of Images. What follows is the edited transcript of a conversation that took place last October at 88 Fleet Street, London, in MayDay Rooms, recently set up as a safe haven and center for archives of dissent and experimental culture threatened with loss or erasure.

Iain Boal: Let’s start with the image of the “Marlboro Marine” by the photojournalist Luis Sinco, who was on assignment in Iraq for the Los Angeles Times.

Julian Stallabrass: So this must be at the second battle for Fallujah, right?

IB: Yes, that’s right. November 2004.

JS: And Luis Sinco was embedded with a marine company in very heavy fighting, and took the picture of a marine, he didn’t know his name at the time, but his name was James Blake Miller, twenty years old, from a coal-mining town in Kentucky. So the marine is resting after the battle on a rooftop, smoking a cigarette, and Sinco took a close-up, just as the sun came up, and didn’t think anything much of this picture; it was just one among a number he took at that time. But there was something about it which was extraordinary, at least for the mainstream press and media on the lookout for U.S. heroism: a picture of a battle-hardened, battle-weary but somehow perhaps triumphant, at least resilient, marine smoking a cigarette. It was published in over a hundred newspapers and came to the attention of the White House. George W. Bush sent Miller presents by post, and it was quite regularly reproduced as a striking image of America’s success in Iraq, as it was then perceived by many in the media, including the doyen of news anchors, Dan Rather. And the New York Post, when they ran this picture, did so with the headline “Marlboro Marines Kick Butt in Fallujah.”

IB: It’s worth noting that Miller was medically discharged from the military in 2005, and has been suffering from post-traumatic stress since returning from Iraq. The “Marlboro Marine” is in contrast with Nina Berman’s notorious and widely circulated photograph of a wounded marine, home from Iraq, on his wedding day.

It shows the effects of war both on the disfigured body of a marine from a small town in Illinois and on the soul of his childhood sweetheart standing by her man, wearing an unfathomable expression captured by Berman on their wedding day. All the more poignant because we know now that the marriage did not, perhaps could not, survive the terrible aftermath of war.

JS: Both pictures fit into established genres, of soldiers’ faces after battle. There is a long tradition of that, and particularly in relation to the Marines and their various photographic fans, such as David Douglas Duncan, Dickey Chapelle, and Eddie Adams: in all their work there is a very close association with the Corps, a love of it really, and a highly sympathetic depiction of its members. The Berman of course fits into the genre of wedding photography, the couple posing formally in their finery in front of a studio backdrop.

IB: The most obvious comparison, I suppose, more than the Berman photograph, is with the famous image taken by Don McCullin at the battle of Hue in Vietnam in 1968.

JS: Yes, of a shell-shocked marine, or this is how it is regularly described, anyway.

IB: It sure looks like it. But there’s no cigarette to signify repose or weary satisfaction after the killing. McCullin’s marine is holding — actually, holding on to — the barrel of his weapon. Same genre, I agree, but there’s a profound difference between the two photographs. It’s interesting to learn that Sinco didn’t make much of his “Marlboro Marine” photograph at the time.

JS: No, he has said in interviews that he thought the most marketable pictures, and the most interesting to the newspapers, would be those of intense combat. For sure they were on the lookout for that, but it’s this picture in particular that really resonated with people, or at least with the media. And I think that one of the reasons is that modern combat is incredibly difficult to photograph. For the most part you’re behind the people you’re photographing, so it’s comprised of pictures of people’s backs; the enemy is usually invisible and munitions in flight are invisible. Camouflage is not terribly photogenic, so it’s really hard to photograph combat well. It’s an extraordinary skill that very few people have: to create photographic drama out of this visually mundane material under fire.

IB: So it’s in the aftermath of combat you’re more likely to get a compelling picture of a soldier’s face for instance, when you’re not behind them. Is that the idea?

JS: In contrasting the McCullin and the Sinco, one obvious thing is McCullin’s choice to work largely in black and white, despite the commercial pressures on photographers of the time to work in color. McCullin did some color work, even in Vietnam, for the London Sunday Times. In this case, it makes for a far more somber effect.

IB: Indeed, though the Sinco doesn’t have the hues or saturation of the kind you discuss in your farewell to Kodachrome. [This refers to my earlier post on Open Space about Stallabrass’s eloge to the Eastman high-contrast color film, introduced in the thirties and discontinued in 2009, whose complex processing requirements could not survive the digital revolution.]

JS: I think a lot of it has to do with the eyes, actually, and seeing those eyes very vividly. In the Sinco, they’re narrow, which seems to suggest determination, perhaps, and he’s a “sharpshooter,” as the press would call him, their euphemism for sniper. His killing is of a very deliberate and personal kind, and through his scope he would see his victims fall and die, and be able to count them. McCullin’s subject is holding his hands around the barrel of the gun in such a way that he can’t use it, and his eyes are mostly in shadow. He seems haunted, a more passive and a weakened figure. There’s probably something to say about the relationship between McCullin and the marines at Hue. He had much more freedom to move around freely and photograph civilians with as much compassion as he did the soldiers. He was not on a restrictive embed, in which leaving the unit would mean serious trouble. He takes a famous picture of a Vietnamese soldier who’s been killed and had his possessions looted and his body abused by the marines: at that point, McCullin said, I really hated those guys.

So I think his relationship with these soldiers is quite ambivalent at best, whereas the embedding system in Iraq was supposed to produce, and often did produce, a very close identification with the soldiers, which came out of being in their constant company for weeks or even months in some cases, being protected by them, being fed by them.

IB: Embedding is part of the changing face of war. It was a policy response by the military to growing agency among the world’s colonized peoples in the context of new developments in the technics of communication, not least of course, the circulation of images. Developments, in other words, in the generalized spectacle, which has resulted in a proliferation of “perception managers” in the Pentagon no less than in the corporate headquarters of dog food manufacturers. I would also mention that the history of war photography between the moment of McCullin’s picture and Sinco’s “Marlboro Marine” — between, that is, the U.S. invasions of Indochina and Iraq — intersects with the history of medicine and psychiatry. Specifically the growing recognition — or construction, depending on your view — of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). As a formal diagnosis it turns up in the standard Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), around the time of the second edition, which is published in 1968 — that would be interesting to check. Certainly the phrase, and the acronym, has entered popular discourse by the time of the battle of Fallujah, and would be informing the reception of such photographs.

It’s worth noting that the DSM has its roots in Second World War psychiatry, and the foreword to the first edition, published during the Korean conflict in 1952, acknowledges that its categories are similar to those of the Armed Forces nomenclature. Informally, fellow soldiers and veterans would immediately recognize the “thousand-yard stare,” or what in the First World War was called “shell shock.” Ever since the Battle of the Somme, when 40 percent of casualties were estimated to be suffering from shell shock, the military high command has oscillated between acknowledging soldiers’ trauma and denying it. Many returning vets in 1968, wearing expressions like McCullin’s marine, were walking the streets of San Francisco, homeless. I remember being surprised to hear from Ron Davis, founder of the San Francisco Mime Troupe and an austere Brechtian, how sympathetic he was to the hippies because of their generosity and openness to Vietnam vets who were often welcomed without judgment into the communes of Haight-Ashbury — with their buzz cuts and thousand-yard stares. Davis believes that many lives were saved, suicides averted.

Of course, there are distinct limits to what photography can capture of the mental life of soldiers either during battle or in long aftermath of conflict. During a recent address in Montreal criticizing Western conceptions of psychological disorder and the mental health industry, the psychiatrist Derek Summerfield showed a McCullin photograph of a somber-looking woman sitting alone on a log, presumed to be a civilian casualty of war. Summerfield had seen this picture in a McCullin exhibition but later realized that his knowing McCullin to be a photographer of war zones had led him to falsely project trauma and victimhood onto the image of a female elder from Irian Jaya.

JS: It’s a fascinating subject, this one. I don’t know a great deal about the history of PTSD and its diagnosis, but it does seem to be historically and geographically variable. It is interesting that the British troops in Iraq, for instance, suffered from it much less than the Americans. One possible explanation for that is the British saw much less action in Iraq than the Americans. But I think there’s something else. It’s important to say that James Blake Miller is indeed a PTSD sufferer and it’s caused him and the people around him a great deal of suffering, and he’s had suicidal spells, and is seriously affected by this. And Sinco, talking about this, said that “Miller and I, we in large part experienced the same things, but the reason I don’t have PTSD and he does is that I didn’t do any killing.”

So the condition seems to be partly to do with men dying around you who you care a great deal about, but it’s also about what you did there: and in that sense war seems highly variable. How many soldiers came back with crippling guilt about the things that they’ve done, as so many did from Vietnam?

IB: Yes, I’m sure you’re right about the historical and cultural variability. It is probably wise to be suspicious of universalized categories of mental distress and human suffering — whether through biologizing or some global psychiatric grid. Derek Summerfield, again, reviewing the history of PTSD, contrasts the current neoliberal thrust towards individualized — and commodified — grief counseling with the way that communities used to deal collectively with disaster. He takes as example the socialized response by the villagers of Aberfan in Wales to the catastrophic collapse of a colliery waste tip which inundated the primary school one morning in 1966; 116 children were killed by a river of slurry forty foot deep.

“Hard to tell from here. Could be buzzards. Could be grief counsellors.” From The New Yorker (June 7, 1999)

In this context it’s worth noting that the iconography of war and catastrophe is typically inflected by national characteristics. I know nothing of the imagery used in newspaper accounts of the Aberfan disaster, though one can be fairly sure that it drew on visual clichés of the pithead and Welsh mining communities — winding machinery, tailings, the working-class terrace. In the case of the Sinco photograph, it obviously references the Marlboro Man, one of the most famous in advertising history, transforming what had been a “woman’s” brand into a cigarette that traded on anxious masculinity in twentieth-century urban America. And in turn, of course, the Marlboro Man depended on the figure of the cowboy, which for a century was a central trope through which the national narrative was compulsively reworked — the frontier, the west, seizure of a continent, genocide. This history must fit somehow into the production, circulation, and reception of the Miller photograph.

JS: I think it was seen as an image of victory.

IB: Of victory? A job done?

JS: Yes, a job done, and it could be seen that way because there was so much concentration on battle and on the troops of the Coalition; in a familiar scenario, civilians, Iraqis as a whole, and Iraqi politics were ignored. And this focus on the troops brings up the whole issue of humanism and its relation to documentary and news photography.

IB: Yes, let’s get to it.

JS: In Vietnam, McCullin takes a lot of pictures of U.S. and ARVN soldiers; he doesn’t often photograph the enemy, because he can’t, but he deals with soldiers and civilians on more or less equal terms. In Vietnam, most of the participants — Vietnamese and American — were conscripts; after all, they didn’t have any choice but to be there. But the Sinco is part of a different phenomenon, I think, in which the U.S. Armed Forces have become a powerful image-producing and image-managing entity. They make many images directly, and they cause many others to be made. The images their professional soldier-photographers and videographers make are given away to the press agencies, which are then poured into the magazines and newspapers and news channels without much credit. So you might be looking at military propaganda without realizing it, and the focus is very much on soldiers, on their difficulties, on their traumas, on their conduct and so on, and civilians rarely got a look in. Even those photographers who were working independently, outside of military protection, found it hard to get stories about civilians published. The smaller, volunteer armed forces, with their large component of elite troops and special forces, get used in an integrated military-media strategy: dangle the Marines in front of the enemy to draw them out so that the Americans can bring full weight of munitions down on them; and in the process, generate some spectacular battle imagery.

IB: And since we’ve been asked to consider the relations between war photography and humanism, what would you say about McCullin in this context?

JS: Well, McCullin I think is clearly a liberal-humanist photographer, with all the virtues and the limits of that position. He’s working for the Sunday Times at the time, which is also of that character, under the editorship of Harold Evans, which took its photojournalistic humanism seriously, and allowed photographers the funds and freedom to pursue projects in depth. Sinco’s pictures issued into a media which is much more right-wing, much more business-oriented, and in which photojournalism had been in crisis for some time. In a sense, the war on terror helped to revive photojournalism, but it was revived in very different circumstances, and in circumstances in which there was much less journalistic expertise around foreign affairs because this was one of the areas which had been neglected and hollowed out for so long in favor of chasing consumer and celebrity stories. As a result many of the reporters and photographers who went to war in Iraq knew very little about it, and the kind of things that were easiest to find out were about the Western military, not, as I have said, about local politics.

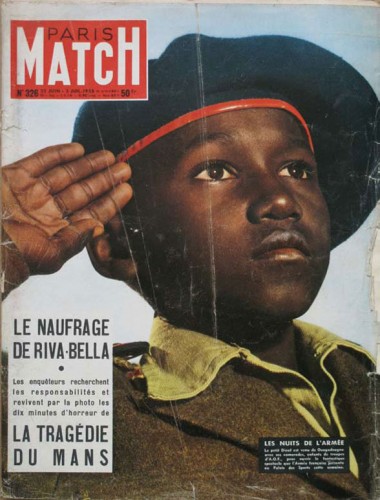

IB: Certainly suspicion of most humanisms is in order. Likewise of “situation ethics,” and the idea that extreme situations such as war and catastrophe give special access to some universal human essence, or a moral code derived from it. In fact, all universalist claims made under conditions of inequality — whether in a colonial or neocolonial context, or in societies riven by class, race, and gender divisions — are likely to be ideological and contain parochial projections. For related reasons, in the writing of Retort’s Afflicted Powers we coined the term “military humanism” to describe the deployment of human rights discourse in the pursuit of imperial objectives — mercy by any means necessary. I am reminded of Roland Barthes’s analysis in Mythologies of the 1955 Paris Match cover photograph of a black French soldier saluting the national flag.

JS: OK, let’s start with Barthes and the issues of class and race and empire. I mean of course he’s right, he’s very clearly right that Sunday Times–style liberalism encompassed many, many exclusions — and false inclusions — and there were all sorts of difficulties about it. Yet from the perspective of established neoliberalism and its media, it becomes clear that there are worse things than liberal humanism: an insouciant focus on shopping in the face of growing inequality, environmental degradation, and military oppression would be one of them!

IB: Fair comment.

JS: And it’s not always true that humanist photography was exploitative and based on some ideologically dodgy idea of the Other. If one thinks about those forms of photography in France in the postwar years, at least into the late 1960s, you had photographers such as Robert Doisneau and Willy Ronis making very sympathetic and beautiful pictures of suburban Paris and its inhabitants. The photographers were part of the milieu that they photographed, and their pictures were published in the Catholic and the Communist papers that those people read. So there was some equality between subjects, photographers, and indeed the media.

IB: So are you just saying that the fact that they were not for a national press, that they were local, made a difference?

JS: It’s hard to put across such perspectives from the point of view of mobile transnational capital, though there may be things to be said about an emergent global humanism in visual form on social media. But the respectful treatment of working-class and petit-bourgeois cultures that you found in Doisneau and Ronis and many others is much rarer in the mainstream media now. You can contrast such work with the dark celebration of U.S. military culture in some journalism and photography — think, as an extreme example, of the collaboration of Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger over Restrepo, a forward operating base in Afghanistan. Think of the connection between those tattooed racist killers and the lowering of standards for admission to the U.S. military during prolonged wars: it took place in Vietnam with McNamara’s “Project 100,000,” which channeled what he called the “subterranean poor” who would normally have failed to meet the qualifying standards in war. The “Moron Corps,” as they were brutally known in the military, were far more likely than ordinary troops to enter combat and be killed or injured. In Iraq, standards were lowered too, as Matt Kennard has shown in his book, with the result that the U.S. infantry comprises Nazis, gang members, and career criminals.

Hetherington in his book Infidel offers a disturbingly intimate and compelling portrait of such people. The pictures are not so far from that kind of homoerotic celebration of Nazism that you get in Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. Their training is designed to dehumanize them, to dehumanize the enemy in their thinking, and to make of them unthinking and unhesitating killers. It may not be completely effective, of course, or only so for a time. Again and again, in accounts of the U.S. military, parallels are made with the frontier mentality: to the genocide of the people of the First Nations, though of course it is not put like that. There’s little humanism in that culture, but rather a stark us-versus-them divide, often defended on the grounds of religion.

I think the other thing you could say about the critique of humanism is that it issued from a time when much of the Left was very confident that we were entirely socially constructed beings. Given what has been discovered about our brains, genes, and bodies since, I think we’re far less confident of that.

IB: Well, I certainly wouldn’t disagree that a one-sided social constructivist view is as hopeless as crude biologizing. And by the way, with respect to crude and reductionist biologizing, you can hardly do better than some of the speculative brain science trading on the pretty pictures enabled by new imaging and scanning apparatus. On the topic of the new imaging technologies, I wonder how “photography from above” — satellites, CCTV, drones — and “photography from below” — by a citizenry armed with ubiquitous handheld phone cameras — will affect views of the human.

JS: Actually, the view from the air has quite a long history going back to Nadar photographing from his balloon.

IB: Which presumably can be related to an even deeper history of Renaissance representation of the commanding prospect.

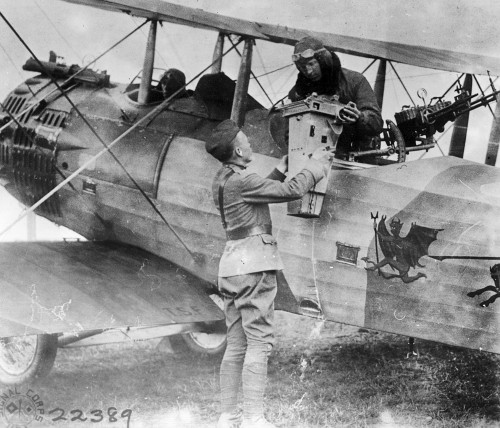

JS: In the First World War, the battlefield was first photographed from the air for reconnaissance purposes, then those pictures find their way into illustrated magazines and become famous as alien images of the destructive force of modern warfare, those towns, villages, and farms turned into moonscapes.

IB: In this case human portraiture is out, impossible at such distances.

JS: Trevor Paglen is a really interesting case because he is attempting to push at the limits of visibility. He is turning lenses normally used to make pictures of the stars onto secret military bases in the U.S. Because of the heat shimmer you get very painterly, suggestive images that often do not yield much information but stand in for all that we cannot know. Sometimes you can read the insignia on an aircraft tail, and Paglen has done some valuable work tracking down rendition flights, in association with many plane-spotters. There’s a formalist aspect to his work which is important, as is his evocation of art-historical references. His is a conceptual project, and in that sense it’s very firmly a museum and a gallery project, and one which is a long way from photojournalism.

Trevor Paglen, They Watch the Moon, 2010; C-print; 36 x 48 in. (91.44 x 121.92 cm);

Courtesy of Metro Pictures, New York; Altman Siegel, San Francisco; Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

IB: And made possible by the new techniques of digital reproduction and printing, which permits Paglen and company to scale up in ways that were impossible a generation ago. However, away from the gallery, in a street setting, including war zones like Syria, there are interesting developments.

JS: So much of the video and photography that came out of Syria, especially in the beginning but even now, has been due to the mass enabling of citizen journalism by social media, and the widespread ownership of cameras that are easy to use. It used to be a quite peculiar habit to take photographs every day. Now it’s something that huge amounts of people do, in war situations or otherwise. The difficulty, of course, is that without the institutional assurances of the mainstream media (which are themselves pretty faulty) you have little idea of what you are looking at: is it made by a bystander or a participant, has it been manipulated, and if so, how? Where and when was it taken — and often, given the quality of the work, even: what does it show?

IB: A good question.

JS: The institutional faith of sanctioned photojournalism is still quite powerful, though subject to far more skepticism than it used to be. The ubiquity and immediacy of social media journalism seems vitiated by the issue of trust.

IB: Nevertheless, I can’t recall anybody who doubted the veracity of the “wired Christ” and the other Abu Ghraib torture photographs. Including myself. I wonder why.

JS: The routes through which the Abu Ghraib pictures came to light made them hard to doubt. There are other pictures that show much worse things — including digital pictures of U.S. troops raping Iraqi teenagers — which never had impact of the Abu Ghraib pictures, because no one is really sure whether they are authentic or not.

IB: The new technics of digital reproduction and manipulation finally break any connection between the fall of photons and their traces on a light-sensitive medium. End of an era, and end of our conversation.