Searching for Francis McComas

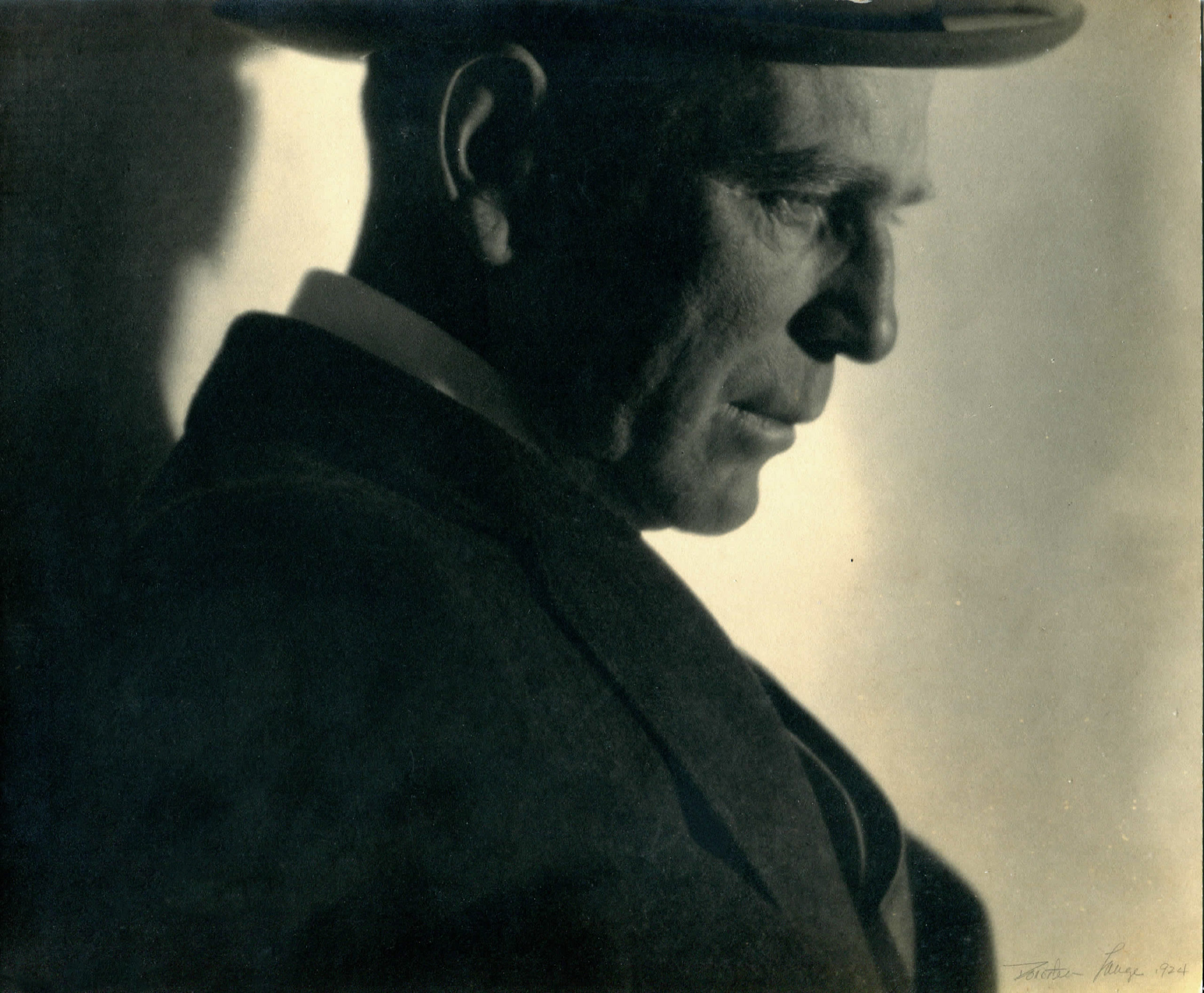

Francis McComas, 1924. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Image courtesy of Le Grande Dix.

I was daydreaming in a quiet California art gallery in 2017, surrounded by racks of early twentieth century landscapes, the craquelure of aging paint reflected in the ornate gilding of frames hand-carved more than a century ago. A ringing phone broke the silence. On the other end, a client spoke, “I want you to find out everything you can about Francis McComas.”

If you’re asking, Francis who? — you’re not alone. I’d specialized in historic California paintings for seven years and even still I could only muster a brief summary of his life. Born in Tasmania, immigrated to California around the turn of the century, became a successful watercolorist in San Francisco, married a fellow painter. And then, sometime in the 1920s, disappeared.

My client already knew the summary; a prominent collector and student of history, he’d been looking into McComas’ story for some time. The problem was, there wasn’t much of a story to find: there were no books about him, no journal articles, very little research or analysis. The only “real” biography I could put my hands on at the time was a dusty, uncited WPA monograph from the 1930s. I called my sources, a close-knit network of California dealers: no one could even agree on when McComas was born, much less where he went to school, what he was like as a person, or why he disappeared. His work popped up on the private market now and again for well into six-figures, but his life was an enigma.

So, I started digging.

I didn’t know it then, but this effort would become the singular focus of the next two years of my life, culminating in a McComas retrospective at the Monterrey Museum of Art. As my research unfolded, I ranged thousands of miles across the US West, tracking down leads in museums and private collections, poring over troves of personal letters unread for a hundred years, interrogating archivists from Los Angeles to Paris to Tasmania. Slowly, the answers started coming in.

The facts read like a pulp novel. McComas was renowned as a boxer, drinker, and Lothario — but also an authoritative intellectual and orator. He exhibited in galleries and museums around the world. He vacationed on the Ionian Sea with the Prince of Greece and made films with Cecil B. Demille. He lunched with Charlie Chaplain, yachted with Phoebe Hearst, and helped purchase the famous illuminati retreat known as Bohemian Grove

Relda Morse, Francis McComas, and Sam Morse, the ‘Duke of Del Monte,’ c. 1920s. Image courtesy of Le Grande Dix.

The more I learned, the more unbelievable the story became, and the more obsessed I became. I knew something else was there, obscured by the spectacle and flourish of this remarkable life — something that would not only sate my curiosity but reorient my understanding of Californian art history.

McComas was drawn to the landscape of the western United States, from the lush, meandering coastline of the Pacific to the barren climes of Arizona desert. He lived in Northern California for most of his life, though he traveled widely. I’d been tracking his movements through the teens, twenties, and thirties, when I began to notice that his reductive, highly geometric works seemed curiously in advance of his fellow Californian painters. And there was something else, too, something more subtle, a vein spreading from Paris to New York, snaking and branching but moving ever westward, finally crashing against the Pacific in 1915: following McComas, I realized I was also following the path of Western visual modernism.

Certainly, this path began long before and continued long after the sliver that lay beneath my scope. But in this section of the journey, from the studios of the Parisian proto-Cubists to the inchoate beginnings of modernism in San Francisco, every step along the way, McComas was there. He was in France for the Cézanne and Braque exhibitions of 1907, the formative moments of Cubism; he exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, the first great show of modernism in the US; he was a curator of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), the largest art show ever held in California and harbinger of modern art in the region; his work was in the foundational collection of the San Francisco Museum of Art, later to become SFMOMA.

I was reading a transcript of the 1916 Symposium on Modern Art, a public debate in which McComas argued in favor of avant-gardists over San Francisco’s traditionalist, faux-European academics, when it struck me: This wasn’t just some early progressive painter — this was California’s first modernist.

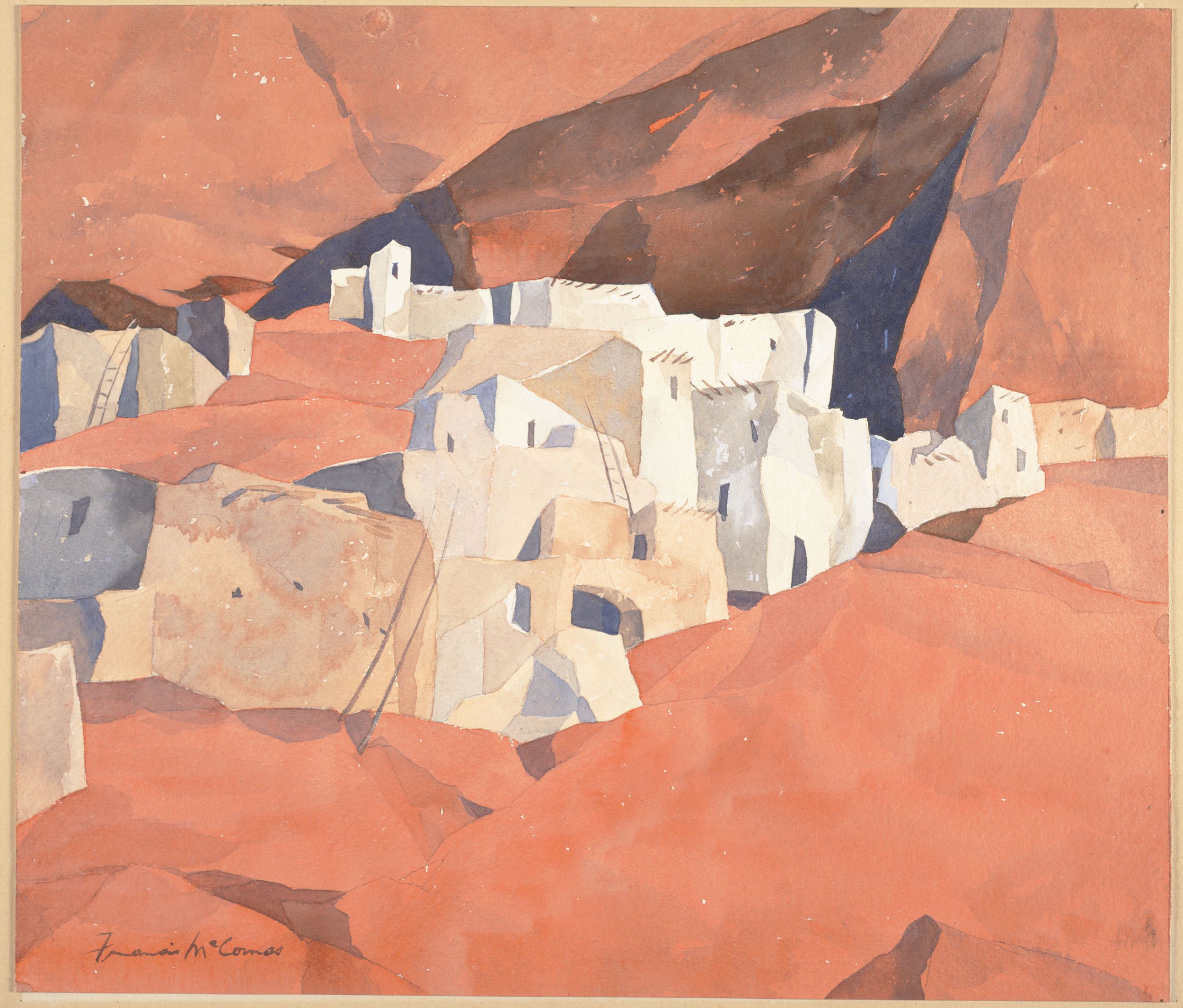

Francis McComas, Cliff Dwellers, c. 1915-1919. Watercolor, 13 ¼ x 15 ½ in. Collection of SFMOMA, gift of Albert M. Bender

It was the answer to a question I hadn’t even known to ask. While modernism’s arrival in New York via Europe has been well studied, given the dearth of research on its emergence in California you’d think that one day it just showed up. But, of course, things don’t just “show up.” Effect follows cause, and battles for progressivism are hard won by dedicated activists fighting for very specific goals.

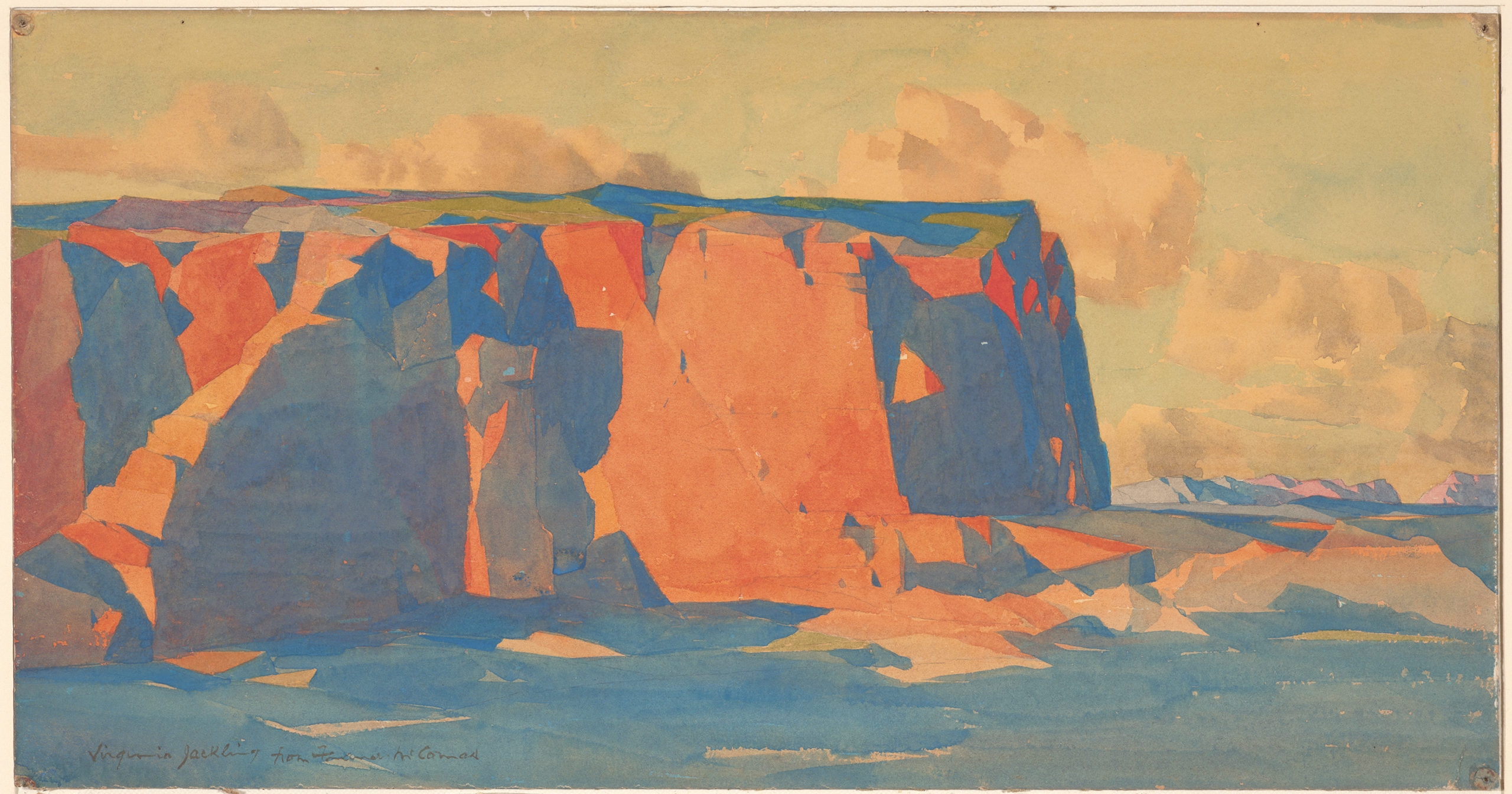

McComas had gained prominence shortly after his 1898 arrival in San Francisco for his work in the then-popular style of California Tonalism, a Barbizon-esque form of plein air landscape painting reminiscent of European genres of the prior century. But over the ensuing years, as he travelled throughout the great art centers of the Western world — Paris, London, New York — he began to see the arts of California as stultifying and antiquated. Around 1910, he made a conscious decision to embrace the idioms of emerging European modernism, abandoning the Tonalist conventions of softened form and subdued palettes in favor of deeply faceted polygonality, jarring perspective, and audacious, fully saturated colors.

While much of the culturati west of the Mississippi was still waking up to the marvel of Impressionism, McComas and a small cadre of like-minded, similarly well-travelled artists, including Arthur Mathews, Xavier Martinez, Eugen Neuhaus, and Arthur Putnam, had coalesced around San Francisco’s Bohemian Club, and were beginning a campaign for radical progressivism in the visual arts. The Mark Hopkins Institute of Art (today known as the San Francisco Art Institute) and its affiliate member organization, the San Francisco Art Association (SFAA), had been the seat of academic connoisseurship and the arbiters of taste in the region for decades, and it was upon them that McComas loosed his most withering opprobrium. In a speech published in The Oakland Tribune on October 11, 1914, he said:

“Here in San Francisco, an institution lies rotting on a hill, doing its best to throttle and strangle art, and not knowing enough to realize that where it aims at murder it is achieving only suicide.”

He condemned Hopkins and SFAA for their dull imitations of anachronistic European academicism. Their galleries and studios were “morgues” peopled with zombie painters. He lambasted the de Young Museum, the only large-scale exhibition space in the city besides Hopkins, quipping in a July 19, 1913 article in the Bay Area weekly Town Talk, “This latter great institution is for the family gems which people are tired of having around the attic.” Of the city’s critics, he said, “they fear to tell the truth or else they don’t know it.”

Despite his attacks on the traditional art world, by the early 1910s McComas was one of the most popular painters in the city. It was rumored in the press that he was the most expensive watercolorist in the world. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, given his quickly rising star, that he was chosen as a curator for the PPIE, the “World’s Fair” in San Francisco held to commemorate the completion of the Panama Canal. The fair’s committee of California jurors was composed of McComas, Mathews, Neuhaus, William Wendt, and Paul Gustin; McComas and Mathews were further recognized as “artists in whom the directors judge the fundamental importance of American art to be incarnate,” and were given their own gallery exhibitions — the only two living California painters afforded the honor, according to The Star Tribune in Minneapolis.

Francis McComas, Mesa, c. 1917-18, inscribed “Virginia Jackling from Francis McComas,” Collection of San Francisco Legion of Honor, gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Gill.

To their credit, the directorate of the PPIE took a major risk selecting McComas, Mathews, and Neuhaus; the artists were well known for their progressive inclinations and it was possible they would alienate more conservative audiences should they stray too far from accepted norms. But the directors agreed that a World’s Fair should err on the side of the spectacular, and so both the McComas committee and other art juries were given a wide berth to select work.

When the galleries opened, it was the largest exhibition of artwork ever held in California, nearly ten times the size of the Armory Show, with hundreds of artists representing thousands of works. Nineteen million people — almost one fifth the population of the United States — attended the Expo, and for nearly all of them it was there that they discovered this strange and exhilarating new thing called modern art. Far from alienating the public, the show proved such an attraction that after the Expo came down in December 1915, McComas was selected to co-curate a four-month Post-Exposition Exhibition (PEE), to be held in the Palace of Fine Arts. Travelling east, McComas and his co-curator, John Trask, visited Chicago, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Boston, and New York, selecting work to replace those which had already been sold or returned to artists.

They gathered pieces from the country’s most visionary — and polarizing — modernist painters, including George Bellows, Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and Max Weber. The works they chose were so divisive that the Symposium on Modern Art was convened to debate the dangers of what his detractors saw as a strange and perverse abuse of artistic values. The leading institutional voices of the Bay Area, including painters of the SFAA as well as faculty at Hopkins and UC Berkeley, lined up to oppose McComas and Trask. Among their most ardent critics, Arthur Pope, a professor of art and aesthetics at Berkeley, stated outright that he was “against [modernism] rather strongly,” calling Cubist and Futurist artists “occultists” and “frauds.”

McComas did not mince words in his retort:

They [opponents of modernism] are labeling themselves as being rather dull, and rather unintelligent, and rather without imagination. And I am sure they do not want to saddle themselves with those particular labels. […] It is not this movement that the plea should be made for. It is rather for the people who insist on staying out of it.

The traditionalist aesthetes of Hopkins and the SFAA were unmoved by McComas’ indictments. But what they didn’t know, or were perhaps too afraid to admit, was that, in the eyes of the public they had already lost. Following the events of 1915-1916 there was an explosion of visual modernism in San Francisco, California at large, and indeed throughout the US West. What scholarship there is on the influence of the PPIE and PEE does acknowledge their part in fostering progressivism in Northern California’s visual arts, but what has been missed is McComas’ leading role in shaping the character of these events and through them the artistic landscape of California.

Francis McComas, Former Mack Residence, c. 1920s. Oil on canvas, 53 ½ x 78 in. Collection of Monterey Museum of Art.

But this begs a question: if this McComas guy’s such a big deal, why haven’t I heard of him? Well, partially, it’s because he didn’t want us to. At the height of his fame in the early 1920s, McComas withdrew from the public eye. For the last fifteen years of his life, he refused solo exhibitions even as the country’s leading gallerists and museum directors implored him to mount a show. He gave work to small group exhibitions here and there, but only to those with whom he had a personal connection. He never said why he turned his back on the public art world. Some speculated that he’d grown weary of the work involved in mounting large solo shows. Or maybe he’d simply tired of reading his name in the city’s art (and worse, gossip) columns. But I think there’s a simpler explanation: he was eschewing an art world that was too conservative, too old fashioned for his modern sensibilities. “We want fewer heroes and more painters,” he told Town Talk in 1913. “Good men [are] crowded out by men who chose the profession instead of being chosen by it.”

But by the time the zeitgeist of California caught up to him, McComas was more than a decade removed from the public eye. When the art history of the region was codified many years later, his style did not fit neatly into the formalist analyses used to construct artistic genealogies — as was the wont of art historians in the first half of the twentieth century. That his rhetorical role in the movement is today largely overlooked seems an unfortunate consequence of this original oversight.

Francis McComas passed away at the Monterey Hospital at 5:15 A.M. on December 27, 1938. Two days later, in a modest ceremony attended by family and friends, against the melancholic glow of the setting sun, his ashes were buried in the shade of a cypress tree on a cliff overlooking the cool waters of the Pacific. And the world began the long, slow process of forgetting.

Before the following decade was out, most of his closest allies in the early fight for California modernism — Mathews, Martinez, Putnam, Trask — were gone. By 1963, the last of his friends from the PPIE, Eugen Neuhaus, had also passed away. Though McComas’ name would drift through the pages of the art press over the following decades, there were few left who understood his importance. When his wife, Gene, died in 1982, almost none remained who had witnessed his triumphs firsthand.

By 2017, when our story began, his gravesite had long since been lost to time. It had sat for years, maybe decades, overgrown and unvisited. I went looking for it; I felt I owed that to him, to his legacy. And when, two years later, after scouring the historical record, satellite photos, and digging through acres of California dirt I actually found it, even the owner of the land within which McComas rested was unaware of his presence. It was that moment, more than any other, when I knew his story must be told.

Francis McComas didn’t live to see the full height and breadth of the great divaricating tree of California modernism. But if we brush aside the overgrowth of history, if we dig deep enough, the spring he struck in the 1910s is still there. Still nourishing us, still sharing its beauty and knowledge and the exhilaration of discovery.

Gravesite of Francis McComas. Undisclosed location, Monterey Peninsula. Image courtesy of Robert Pierce.

Comments (5)

Thank you for this labor of passion! I’m doing my own passion-search biography, and the tangled web led me here. There are so many fascinating stories told only through the deep search …

Good job Rob!!!

Thank you for your info filled article. I have loved McComas for decades and have wondered why on earth it was so hard to learn more about him! PLEASE, if you are capable, or know of someone who is….please write a book on his work and let us see a collection of his paintings in such a work. A coffee table book for Francis McComas is long over due!

Francis McComas was fascinated with the works of the Indians of the Southwest. Their geometric patterns and traditional designs were a precursor to modernist styles. He became intrigued with the ancestral pueblo dwellings and buildings, hence his watercolor painting “Cliff Dwellers”. He disappeared into their world, and roams there today.

Thank you for the fascinating story. His work is wonderful. floating houses and antelope! Lovely color.