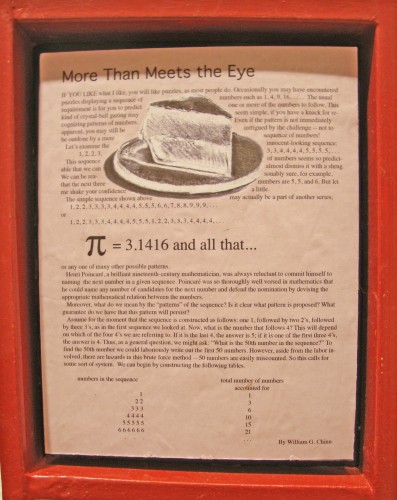

Flo Oy Wong at the Luggage Store

Flo Oy Wong: The Whole Pie opened last week at the Luggage Store Gallery.

This is a particularly appropriate venue for showcasing Wong’s work. Not only do suitcases (and other migration metaphors) play a prominent role in Wong’s oeuvre, but her ambitions as an artist-activist coincide quite precisely with the aims of the collectively operated nonprofit Luggage Store Gallery to “amplify the voices of the region’s diverse artists and residents, to promote inclusion and respect, to reduce inter-group tensions and to work towards dispelling the stereotypes and fears that continue to separate us.”

Wong is a teller of unspoken (or unheard) stories that bring people together. Her multilayered work combines everyday materials (rice sacks, items of clothing, suitcases, beads, envelopes, snapshots, flags, sequins, newspaper clippings) and mundane expressive vernaculars (stenciling, stitchery, cooking, cutting and pasting) to voice historically muted narratives that sometimes affirm, sometimes contradict, and always unsettle our received ideas about who we are — individually and collectively. She dismantles barriers that separate us from aspects of our selves, families, histories, and communities. Similarly, the Luggage Store Gallery strives to nurture and expand community through multidisciplinary, polycultural arts initiatives “accessible to and reflective of the Bay Area’s residents.” Both the Luggage Store and the artist whose work will be featured there through December 28 advocate for the free circulation of creative expression among the diverse populations that call the Bay Area home.

The retrospective Flo Oy Wong: The Whole Pie, cosponsored by the Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center (APICC) and curated by Pamela Wu Kochiyama, Darryl Smith, and Laurie Lazer, shows how Wong’s unflagging commitment to social justice has materialized across a forty-five year artistic career. In addition to classic examples of the artist’s work, which include some early self-portraits exhibited here for the first time, the curators introduce a new mixed media sculpture, Departures‚ and 527: Moussa/Odette Pie‚ a recent creation based a book by Fred Coleman, The Marcel Network, that tells the story of a couple who saved 527 Jewish children from deportation to Nazi death camps. This participatory sculpture incorporates 527 elements contributed by collaborators who include public elementary school students from the alternative Rooftop School, where Wong is currently artist-in-residence.

The living histories to which Flo Oy Wong devotes her practice often concern displacement, immigration, and estrangement — especially stories that illuminate how the Bay Area became home to large and vibrant Asian communities. Personal stories bring home the effects of prohibitive, even punitive, immigration laws, codified social prejudices, exploitative economic policies, and, in some cases, the wholesale confiscation of property, incarceration, or deportation based on race. The rough materials that Wong transforms — for instance, embroidering rice sacks with gold thread — capture both the rawness of minority survival sagas in the U.S. and the resistant humanity of the immigrants who settled this state.

Flo Oy Wong was born at 725 Harrison Street in Oakland, California, on October 28, 1938. Three of her seven siblings were born in China. During World War II, her father worked in the shipyards. After the war, her family operated a series of businesses in Chinatown: a grocery, a Chinese lottery, two restaurants. Wong worked in one of the family restaurants, the Great China Cafe, from the age of five until she had graduated from UC Berkeley and earned her teaching credential from Hayward State University at the age of twenty-three. Wong’s art — such projects as Oakland Chinatown Series (1983-91), Asian Rice Sack Series, (1989-ongoing), Joss Paper Series (1992-97), My Mother’s Baggage Series (1996-98) — manifests, in her words, “the perspective of a woman artist of color in a white society. These projects represent my visual coming to terms with identity, visibility, and social justice.”

Wong has repeatedly grappled with the way her family tree was disfigured by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and National Origins Act of 1924. These laws restricted Chinese settlement in the United States. At the Immigration Station on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay, the U.S. Immigration Service “processed” somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 Asian immigrants between 1910 and 1940. There, members of Wong’s family were interrogated and detained for periods that ranged from several weeks to several months. Sometimes would-be immigrants from Asia remained in limbo at the facility for years.

According to the journalist and historian William Wong (Flo Oy Wong’s younger brother), immigration officers on the island assumed, as a matter of policy, that the claims of Chinese immigrants requesting permission to join relatives in this country were fraudulent — until proven otherwise. Protracted interrogations offered the would-be immigrants an “opportunity” to prove the worthiness of their cases by providing consistent answers to detailed and periodically repeated questions about their claimed identities, origins, and destinations. Approximately one out of every six Chinese immigrants landing on Angel Island was deemed “excludable” and turned away. This represents a much higher rate of repatriation than that practiced during the same period at Ellis Island, the immigration station in New York harbor where hundreds of thousands of European newcomers sought permission to enter America.

Accommodations for detainees on Angel Island were grim and the interrogation process was often frightening and humiliating. The arbitrary sentence of detention punctuated by intense bouts of questioning must have seemed especially torturous to Chinese immigrants with false identity papers — the so-called “paper people,” people like the artist’s mother, whose claims actually were fraudulent. Suey Ting Gee, Flo Oy Wong’s mother, claimed the identity of her sister-in-law in order to join her husband, Seow Hong Gee, in America. Bearing papers that identified her as husband’s sister Theo Quee Gee in order to get around the Exclusion Act, she arrived on Angel Island in 1933 with her three daughters. Upon admission to this country, these Chinese-born daughters officially became their father’s nieces. After giving birth to Flo Oy Wong, Seow Hong Gee arranged a “paper marriage” with an acquaintance, Sheng Wong, in order to assure the official “legitimacy” of her American-born daughter. Flo Oy Wong’s older sisters had to represent themselves (to the world outside of Oakland’s Chinatown) as her cousins.

Flo Oy Wong grew up, like so many members of the Chinese community here in the Bay Area, in a state of confusion about her family history. She refers to herself as a hoo gee nuey (a “false paper girl”) and “a fake Wong” (she has never even met her “paper father”). When she would question her mother about the reasons for these relational fictions the answer she invariably got was a tense “Shhh.” It wasn’t until the immigration amnesty of the 1960s regularized her mother’s status and Suey Ting Gee publicly acknowledged her “paper brother” as her husband that pieces of this family story began to fall in place. Got that?

Despite the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion act in 1943, despite the amnesty of the 1960s, many Chinese family stories remained shrouded in uneasy secrecy. Ed Wong, the artist’s husband, served as a docent on Angel Island and brought home stories about detainees who, in their seventies and eighties, revisited the island for the first time in the company of their American-born children or grandchildren. Some had gone to court to restore their true identities. The artist and her husband, having researched their own convoluted family stories, began connecting with the other “paper people” to record their stories. Word of the Wongs’ interest in this oral history spread by word of mouth among family members, and then from family to family. Flo Oy Wong found a way to spotlight these stories with her art practice.

Adapting the rice-sack format she first explored in the late 1970s, during the ascent of the feminist art movement, the artist stitched the family secrets of twenty-five Angel Island detainees into twenty-five “flags.” Each flag honors the personal history of a “paper person.” The construction of each flag follows the same pattern. Wong sutured a rice sack onto an American flag and then stenciled the surface over with names (both false and true names) and entry dates. The stenciled lettering spells out the process of transformation that individuals undergo when they come into contact with powerful bureaucracies. At first sight, all the resulting rice-sack flags look alike. The standardized format and standardized lettering evokes the dehumanizing aspects of the immigration system, with its quotas and other institutionalized forms of xenophobia. The sameness of the rice-sack flags, at the same time, mocks racist clichés of undifferentiated Asian identity. Stars scattered in random patterns across the rice sacks contrast with the neat symmetry of the underlying American symbols. The two tropes of identity grafted together — one Asian (a lowly rice sack) and one American (the exalted stars and stripes) — encode the tensions and aspirations of the Asian immigrant experience. In 2000, Wong created a monumental installation of these flags, made in usa: Angel Island Shhh, at the Angel Island immigration station. She reconstructed the installation in 2003 at the Ellis Island Immigration Museum.

One of these flags, installed at the top of the steps leading to the Luggage Store Gallery just beneath the exhibition’s title, serves to signify Wong’s complex practice as well as her cultural and political commitments. I asked Wong how rice sacks had achieved the status of a hallmark. Her response demonstrates both her talent for storytelling and her respect for personal history:

I first experimented with use of rice sacks in 1978. I was an art student at DeAnza College in Cupertino at that time. For the student art competition, I sewed on a rice sack to honor my immigrant mother. I submitted the piece to the student show. It was rejected with a comment that said “Not as well thought out as it could be.” I was really disappointed. I took the piece to the final critique in my drawing class. The instructor said that had I done a drawing of the piece it probably would have been accepted. I stopped working on rice sacks until 1986.

In 1986, I met Ruth Asawa. When I saw her wire forms at her house I thought to myself that if she could crochet wire then I certainly could sew rice sacks together. When I came home from Ruth’s house I brought out my supply of rice sacks and began to sew compulsively for four hours.

Her attachment to this material is so profound that it permeates not only her oeuvre but her very identity (ricesackartist is her e-name). Day after day for several years, she says, she stitched rice sacks together, not fully understanding her identification with the material. Then, when she was preparing for a two-person show at Capp Street in 1992, she became aware that a repressed family story was emerging.

To my surprise, I was retrieving the story of my father’s near-fatal shooting by a relative in Oakland Chinatown. When he was shot in 1940 our family was very poor. We had no rice to eat. Relatives brought us sacks of rice. My mother nursed my father back to health. Then she created an operatic talk story of my father’s shooting. She was relentless. Tired of her repetition in telling the story, I tried to shut off her words. I succeeded in erasing the retold pain of my father’s shooting. When I was 45 years old, married and a mother of two and living in suburbia, I reflected on my childhood upbringing in Oakland Chinatown. I started drawing from photographs I had taken at our family restaurant. After completing some of the drawings I began to use cloth rice sacks in my work. I continued to draw and to paint. After a while I just concentrated on sewing on rice sacks to tell extraordinary stories of ordinary people.

The Luggage Store retrospective devotes a significant amount of wall space to the rice-sack narrative Baby Jack Rice Story (1993-96). Here, the artist mobilizes the same formal strategies she used for the Angel Island project to retrieve memories of her husband’s childhood. Ed Wong grew up in a close-knit, predominantly African-American community in segregated Augusta, Georgia. Panels bear silk-screen photos of his neighbors and schoolmates encircled by hand stitched observations such as “They weren’t supposed to be friends.” Each component of these rice-sack installations takes the artist about a month to fabricate. There is a ritual dimension to the painstaking process of all that sewing. Wong pictures her creative acts mending identities, families, community alliances torn asunder by racism.

Food is a recurring theme (and sometimes a medium) in Wong’s work. It appeals for its associations with exchanges around the family table, ritual significance, centrality in community celebrations, and its cultural specificity. Food, like art, nurtures. For Wong, because of her family’s reliance on the restaurant business, food was the source of economic as well as physical survival; it was the currency of her relationships not only to her family members but also the wider Oakland Chinatown community. The iconography of the rice sack enabled Wong to intervene into both her own family heritage and racist stereotypes of Asians. But what about pies, the dominant trope of the current exhibition? Where did this idea originate?

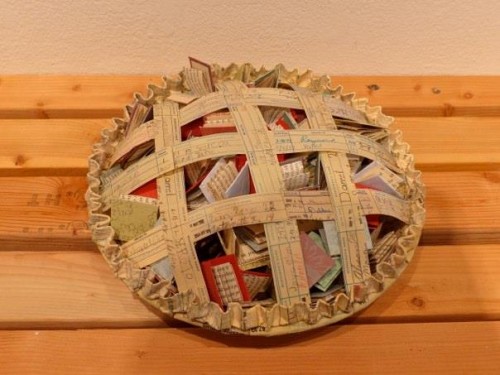

In 2009, I was completing an art residency in Madison, Wisconsin. On my last day, I visited the soon-to-open Children’s Museum. One of the directors gave a friend and me a tour. She showed us an area where the children would be making pies. She said that the museum was looking for professional artists to contribute art pies for a permanent exhibit. I offered to make one. At home in my Sunnyvale studio, I finished a rice sack pie in two days. I liked what I had created. Happy with the results, I sent my pie to the Children’s Museum in Madison. In 2012, I had a solo show in Council Bluffs, Iowa. While I was pleased that the gallery wanted my rice sack works, I was concerned about reaching out to the Mid-Westerners who would come to the show. I knew that my rice sacks would be new to them. I wanted to use a symbol that they could understand you immediately. Because the gallery was attached to a restaurant I thought about using art pies in the show. That would create a connection to the restaurant and it would also engage the customers who loved eat pie at home and everywhere else.

She also wanted to tell stories about diversity in America’s heartland, in cities like Madison, Council Bluffs, and Omaha. With the help of a friend from Nebraska, she began researching the histories of ordinary citizens whose lives are not recorded in books. By the time her show opened at the RNG Gallery in Council Bluffs she had created four more pies.

My pies honored the following people: An older European American man who was a supporter of the Opera, an older African American woman who at the age of 66 wanted to open a soul food restaurant in North Omaha, the African America neighborhood, the Egyptian-born doctor who became the dean of Public Health at the University of Nebraska-Omaha, and finally the gay couple who owned the restaurant and the gallery where I would be showing. I asked each participant to give me objects and materials from their kitchen. I use those to start my pies after completing the research based on their lives. I wanted to know what they had done to get to where they were when I met them. Their stories came straight from their hearts and their lives.

Wong invited seventy-five artists to create pies for her Luggage Store exhibition, which coincides with her seventy-fifth birthday. The contributors received instructions that allowed for a maximum of creative leeway while assuring the ensemble some measure of cohesion. Each artist was allotted twelve square inches of exhibition space. “At first,” recalls Wong, “I wanted only textile pies. [Co-curator] Darryl Smith asked if I would be open to diverse media. I said yes. The results are innovative and creative.” Wong likes the conceit of the pie for its “quintessentially all-American” image and its infinitely variable ingredients.

Zachary Young, Just Eat Me, 2013 (vertical); Ryan Carrington, American Pie, 2013 (horizontal). Photo: Lenore Chinn

The long list of artists whose pies are now on display at the Luggage Store attests to Wong’s reach as a community builder and cultural activist: Kim Anno, Diana Argabrite, Amy Balsbaugh, Eliza Barrios, Theresa Because, Ellen Bepp, B. Stephen Carpenter II, Ryan Carrington, Alan Chin, Lenore Chinn, Mary Ann Cruz, Binh Danh, Gary Day, Mary Day, Shari Arai DeBoer, Erin Fong, Mabel Chin Fong, Dustin Fosnot, Kathy Fujii-Oka, Colette Fujimoto, Erlin Geffrard, Elizabeth Gibbons, Mara Grimes, Ben Wong Halperin, Joe Halperin, Lynn Halperin, Sasha Wong Halperin, Chad Hasegawa, Taraneh Hemami, Melanie Herzog, Deanna Lim Hom, Nancy Hom, Bob Hsiang, Su-Chen Hung, Diem Jones, Betty Kano, Gyoung Sun Kim, Helen Klebesadel, Susan Knight, Nina Koepcke, Lucien Kubo, Janet Chan Lem, Dori Lemeh, Alex & Lauren Lieu, Hung Liu, Tamra Marshall, Gabby Miller, Moira Roth, Gerri Montano, Angelica Muro Dawn, Eileen Nakanshini, Bonnie O’Connell, Pricilla Otani, Debra Priestly, Elizabeth Richardson, Dianne Rosas, Joe Saito Sam, Karen Seneferu, Pallavi Sharma, Roger Shimomura, Judy Shintani, Marianne Ong, Siu, Corinne Takara, Cynthia Tom, Judy Toupin, Alice Vogler, Karen Weller, Andi Wong, Flo Oy Wong, June Yamane Wong, Kyle Wong, Layne Wong, Nellie Wong, Peter Edward Wong, Joyce Woo, Steve Yamaguma, Zachary Young, and Grace Yun.

What will happen, after the exhibition closes, to the seventy-five pies laid out on the custom-made cooling racks at the Luggage Store Gallery? Wong has some ideas about that:

If the pies could be shown again either individually or collectively they would make an impressive show of contemporary culture that brings us together as Americans. My granddaughter, age 7, made her pie to honor Faith Ringgold. If her pie doesn’t sell she plans to donate it to Faith Ringgold’s Anyone Can Fly Foundation. I really hope that many pies are sold. They would add a touch of whimsy and Americana to anyone’s art collection.

The Whole Pie: Flo Oy Wong

November 8 – December 28, 2013

The Luggage Store Gallery

1007 Market Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

415 255 5971

www.luggagestoregallery.org

Wednesday – Saturday 12 noon – 5 p.m., and by appointment

Comments (4)

Dear Flo: I was overwhelmed by reading about your wonderful exhibit. I am so proud to have represented your art and expecially warmed by what you have taught me about the Asian american struggle in America. Keep up your remarkable vision and artisitc verve.

Love, Elly Flomenhaft

The part about Council Bluffs made me smile. It’s where I walked to elementary school in the snow as a child, and from where almost all of my family originates. Can’t wait to visit the show!

Flo, Thank you for posting this comment, which beautifully completes the story I began to tell about the Whole Pie and your long and loving practice.

Tirza: Thank you for writing this comprehensive heartfelt and powerful review about my work. I am awed by the amount of research you did. You honor me deeply with your insightful research and writing. I think that there is one artist name left off of the list. I had invited Eleanor Merritt of Florida to make a pie. Her name is on some of the later lists that we updated.

You captured the essence of my work, which I began at the age of forty without an art degree. It was my disquiet that compelled me to make visual works to include those missing from the contemporary art landscape. At first, I followed artists taught in the existing art curriculum and ached to see people like myself reflected in visual stories. When those were not forthcoming to my satisfaction I jumped like a diver into the art world, falling into a pool of uncertainty. Thank goodness for art historians like Moira Roth and artists like Faith Ringgold who began to address these inequities of the existing canon. They dared to speak of women artists and artists of color. They, along with the late Bernice Bing, painter. became my she-roes. I did not discard Euro-Americ artists completely for the power of Edvar Munch, Gustav Klimt, Kandinsky, Vincent Van Gogh. Edward Hopper, and Robert Rauschenberg spoke to me profoundly. I heard the cries coming from Kathe Kollewitz and the angst of Georgia O’Keeffe. Learning these artists I found courage later reinforced by women artists and artists of color.

My parents created within me a will and stubbornness to work hard. That I have done for 35 years. While as a child I was not encouraged to question anything I still questioned nevertheless. My answers are found in my work and in shows like The Whole Pie.

I am grateful for the hard work that Vinay Patel, Darryl Smith, Pam Wu, Laurie Lazer and others. When they said yes to The Whole Pie it was as if the stars in heaven were shining for me. So many outstanding volunteers like Andi Wong, Victor Yan, Marcus Shelby. Mara Grimes, and Lenore Chinn stepped in to share their generous heart and hands. I owe a depth of gratitude to Theresa Because, my studio assistant for eight years. My husband of 52 years, Ed Wong, is my rock. Then there are brilliant art historians like you, Margio Machida, Martin Rosenberg, Steve Carpenter, and Moira Roth. The muti-talented Nancy Hom gave me an opportuniity to show at Angel Island. The late Karin Higa was an advocate. I did not come to where I am by myself. I consumed the brilliance of those of you who are committed to balancing the canons. In closing, i am grateful for the support of my children, Felicia Wong and Brad Wong, my amazing siblings, and extended family. So, turning seventy five has given me an opportunity to share the stage with additional creative and innovative artists, including my three adorable grandchildren.

With deepest respect,

Flo