George Bolling: Invisible is the Medium

Front: George Bolling; left to right: Mel Henderson, Paul Kos, Bonnie Sherk; not pictured: Tom Marioni; Documentation of Untitled (The Trip) as part of the exhibition The San Francisco Performance, organized by Tom Marioni, 1972, Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, California. Photos: Larry Fox; courtesy University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; gift of the Naify Family

Watching the mesmerizing coverage of the Mars Rover landing this summer, I was reminded of video artist George Bolling’s 1974 pioneering, real-time broadcast event Jupiter Flyby which attracted over 25,000 visitors to the Exploratorium in San Francisco between November 26 and December 2 of that year. During the event, Bolling was stationed at NASA’s command center, sending captured imagery with his added text-based interpretation via a microwave link. His artist-in-residence projects at the Exploratoruim project would include a video analysis of the behind-the-scenes preparation and execution of the Viking 1 landing on Mars. In 1976, The Kitchen in New York presented Bolling’s edited material of manned and unmanned NASA space probes and television transmissions in Earth, Moon, Mars and Jupiter: Video from Interplanetary Space. The following interview was conducted that same winter by Tom Kennedy, a friend, fellow video artist, and collaborator on the Exploratorium presentation. Kennedy currently produces immersive, full-dome digital shows on natural science and astronomical themes for the California Academy of Sciences and other planetariums.

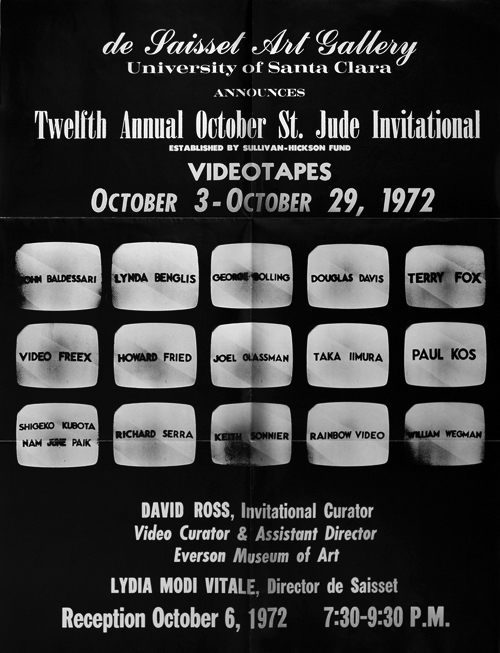

George Bolling (1946–2009) was the first video curator appointed by a museum on the West Coast in 1971. Lydia Modi Vitale, the dynamic Director of the de Saisset Art Gallery and Museum at the University of Santa Clara, was committed to fostering new directions in contemporary art, inviting a number of Bay Area Conceptual artists to have exhibitions featuring installation, performance, and video art. As a videographer, Bolling worked closely and sensitively with several artists recording their first, seminal videotapes, many of which were shown internationally at the time. The video gallery program at Santa Clara also included such video pioneers as Douglas Davis and Bill Viola. Trained as a photographer and filmmaker during his studies at Santa Clara University, Bolling was among the first African-American artists working with experimental video. His interest in documentary and broadcast television dovetailed with working at KQED before relocating to Los Angeles. Bolling’s documentary Newport Beach Revisited (1979), featuring his footage of a road trip with several of the Bay Area artists in Tom Marioni’s exhibition The San Francisco Performance (1972), is being screened regularly at SFMOMA through June 1, 2013.

Invisible is the Medium – An Interview with George Bolling, Video Artist and Curator, de Saisset Art Gallery and Museum, University of Santa Clara, by Tom Kennedy, La Mamelle, v.1(3), Winter 1976, Video Issue.

Tom Kennedy: When did you begin working with video?

George Bolling: My involvement in video began in 1969 when a friend bought a portapak. My first year was spent becoming familiar with the medium. My experience prior to that time had been in photography and film, and video is a very different from film. There were no functional ½” editing machines available. Without editing, it was virtually impossible to manipulate the tape after it was shot. It required then that any shooting be completely choreographed from beginning to end prior to shooting. However, most of my taping opportunities were of artists working in their studios and it was impossible to know what would happen from moment to moment. In doing these documentaries I developed a sense of dealing with the moment, choreographing the shooting in a flow with the situation at hand. There was concern for image but the fundamental concern was time, became time. This is very different from film, which is conceived shot by shot, image by image, with time becoming a result of the equation of images. With video, I found that the objective was to relate the moment first, and the image had to be in tune with that fact (the moment) of the situation.

TK: Who were the artists that were the subject of the documentaries?

GB: John Battenberg and Gary Remsing. I met them through Lydia Modi-Vitale, Director of the de Saisset Art Gallery and Museum at the University of Santa Clara [1967–78]. It was working through her too that I met Paul Kos and began working in video documentation of performance sculpture.

TK: How was documentation different from documentary?

GB: Fundamentally, in documentation you know beforehand pretty much what’s going to happen and about how long it will happen. This provides an opportunity to plan in advance a choreography for the shooting. This doesn’t mean that you plan each step and each second of the shooting. It means that you can consider the gestures in the performance, their value, and thereby the appropriate recording point. Most importantly, you can judge the pacing of the event, which is necessary for insuring that the transition from point to point is of proper duration to at each point at the right time. This is very different from a documentary where you don’t know what happens next, which incidentally makes documentary a very valuable learning situation.

TK: But in documentary, couldn’t you simply ask the artist what he’s going to do in the studio, and wouldn’t that be the same as knowing in advance what the performance is to be?

GB: Not really, for in documentary, the tape is all yours. It’s not the finished sculpture or painting which the artist can keep and sell later. In performance documentation, the videotape becomes the piece to a much greater extent because it is the only physical representation of the performance. As a result, there is a great responsibility to render the performance accurately. It you misrepresent the artist in a documentary, the damage is far less because there is the finished painting or sculpture to counter any misrepresentation—which is not the case in documentation. I had heard rumors before meeting them that performance artists did not want their pieces documented because to you had to be there. Certainly film is no substitution for the real thing because film has its own synthetic time sense. Time is very central to performance. As a video artist I was intrigued by the possibility of documenting performance because I saw time as the central issue of video. Admittedly, video is no substitution for the real thing but it does render time with less distortion than film. The challenge then was to render the performance in video with as little interference as possible; the manipulation of the camera had to be invisible.

TK: Did you have to do much convincing in order to do your first documentation?

GB: I don’t remember any. There may have been some apprehension because it was customary for a filmmaker or video artist to manipulate the medium, shifting the emphasis from the performance to the tape. The first documentation I did was of Paul Kos’ rEVOLUTION [1970]. Through him I was introduced to Terry Fox, Howard Fried, Joel Glassman, Bonnie Sherk and Tom Marioni.

Paul Kos, rEVOLUTION, 1970; 90-minute invisible weight exchange from artist to target. 40 pounds small arms ammunition.; Photo documentation (composite) of action by George Bolling; photos: courtesy the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim, © Paul Kos. The event at di Rosa, Napa, included Bolling’s live video feed into the living room of Rene and Veronica di Rosa and an in-person critique by witness and Newsweek writer Howard Junker. Photographs, Super 8 film loops, black-and-white video, the wood target and ammunition shells were exhibited at the de Saisset Art Gallery in Fox, Fish, Kos, 1971.

TK: Were the requirements for each taping consistent?

GB: As I have discussed them here, yes. Naturally, each piece required its own approach. Sometimes the piece required a stationary tripod approach. Other times I would be able to move about the space. The texture of the video image seems to impart a greater sense of space than the film image. There’s a physicality to the illusion of space in the image. Because of this, it was possible to work invisibly because the only reason for moving would be to change the scale, which lessened the need to move because each viewpoint, if properly found, would be sufficient to hold an entire series of gestures.

TK: For what period of time did you do documentation?

GB: From 1970 through 1973.

TK: And then in 1974 you directed the live video feed to the Exploratorium of the Jupiter Flyby?

GB: Right.

TK: The Jupiter feed was very different from documentation?

GB: The subjects were different, but from the standpoint of video, the concerns were the same. A space mission is choreographed in time according to a sequence of events. So again, the fundamental element was time. I also wanted the viewer to occupy an almost identical relationship to the mission as did the scientists performing the mission—which meant that the use of the medium would have to be invisible. Since the scientists operate by information received via cathode ray tube, the situation for the viewer watching the television monitor was factually very close. Originally I had hoped to set up a computer transistor which would instantaneously translate the mathematical data that the scientists were getting into lay explanation—but this proved to be impossible. We circumvented the problem by developing a lay explanation of the events, which was character generated onto the screen as the lay computer would have done. This lay information was was run according to the mission sequence of events and represented the activity of the scientists for each moment. We had several different video sources, and with the exception of the press conferences, the video sources were chosen as they reflected the concern of the scientists for that point in the mission.

TK: How long did the feed run?

GB: It ran for five days, seven hours daily. The mission was very rich in time, given the communications delay between Earth and the spacecraft.

Public program display in conjunction with George Bolling’s Jupiter Flyby (December 1974) event, photo courtesy of the Exploratorium

TK: How long was the delay?

GB: Forty minutes one way. This delay meant that for any present discussed in the narrative, you also had to discuss what the spacecraft was doing. In other words, at earth the scientists may have been transmitting a command to the spacecraft to take a picture of the planet, but the spacecraft at the very same moment was responding to a command that had been transmitted forty minutes earlier from Earth telling the spacecraft to calibrate an instrument.

Compared to the manned space missions, the Pioneer mission was very slow because there was as much as twenty minutes between events; however, given all the different points in time that had to be discussed for each event, it was difficult to keep up with the activity.

TK: Didn’t the information tend to be too technical?

GB: Perhaps—but I felt that anyone who came to the Exploratorium wanted to know what was happening and had some scientific interest and background. Secondly, given the fact that the feed ran seven hours a day, it would have been impossible to provide a comprehensive overview on the mission because of the random visitor pattern to the Exploratorium. Hence, the intent was to provide information on what was happening each moment, and explain the fundamental scientific principles involved relevant to each event. The visitor could get an overview by watching for a longer time period or from the displays that had been set up in the Exploratorium. It was a very ambitious project and it took the assistance of everyone at the Exploratorium and those available at NASA to make it work as well as it did.

George Bolling,Viking Mission to Mars , Artist-in-Residence project, 5 New Pieces (Artists in Residence: George Bolling, Doug Hollis, Bill Parker, Jim Pomeroy, Dianne Stockler), March 1977, photo courtesy of the Exploratorium

TK: It seems that you are essentially concerned with the distinction between film and video.

GB: The distinction between film and video is becoming harder to make as video technology now makes it possible to edit frame by frame, as one can do in film. I would say that I am concerned that I use video appropriately and to the best advantage.

Left to right: David Tudor, George Bolling, and Bill Viola with lens (composite) at the de Saisset Art Gallery. Composers Inside Electronics, Rainforest IV (1973), electroacoustic environment, performed by members David Tudor, John Driscoll, Phil Edelstein and Bill Viola, November 25, 1975, de Saisset Art Gallery; photos courtesy John Driscoll

George Bolling, “De Saisset Art Gallery and Museum,” Video Art: An Anthology, ed. Ira Schneider, Beryl Korot, Mary Lucier (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976) [click to enlarge]

Twelfth Annual October St. Jude Invitational, October 3-29, 1972, de Saisset Art Gallery; exhibition features George Bolling’s videotape Generations.

Comments (5)

Finding this 9 years later is absolutely so special to me and the Bolling family. Thank you for this and all your kind words. George was my uncle and I wish he was still here to spread more of his work and artistic touch.

Thinking of George and his sweet vision during the New Horizons/Pluto flyby.

Just saw the article, sorry I missed the show. Remembering George fondly.

Gary Remsing

What a lovely tribute to George, who was a sensitive visual artist. Thank you.

thanks you. i always wondered what happened to george richard bolling III