Show Me the Money: Kala Art Institute Part 2

Show Me the Money is an earnest attempt to get people to talk about money in the visual arts.

This is Part 2 of an interview with Archana Horsting of Kala Art Institute. Go here to see Part 1.

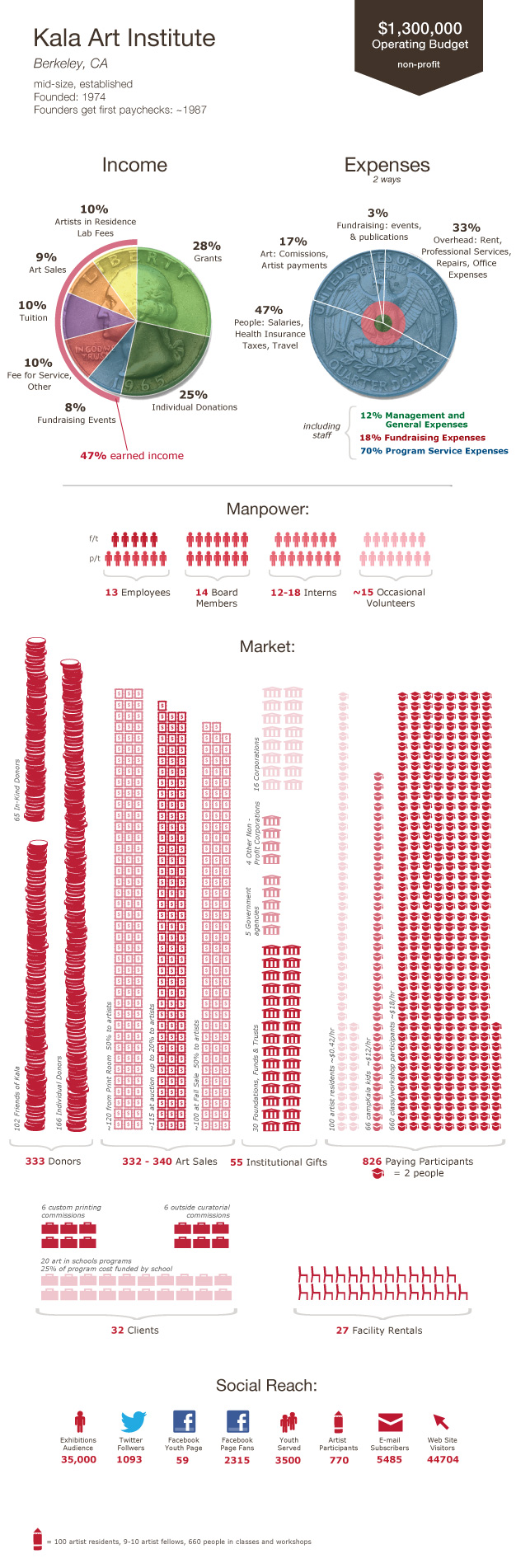

graphic developed with Lauren Venell

Do you ever start programs because you find a funding opportunity, or does it work the other way around (you develop the project and then you look for the funding), or do you develop programs in partnership with a funder?

Archana Horsting: Well, all of those happened. While we have a long history of just doing and then finding the funding as we go along. You’re better off convincing people and educating your funders about what you want to do and what you are already doing: that’s the most necessary funding. It’s fun to try new things but also a headache if you stretch yourself into a pretzel trying to do a 10th program or something. One thing I can say is that our work with kids is by far the easiest money for us to get because there are so many people that want to help with the Artists-in-Schools program and Camp Kala. Kala’s youth art programs are very valuable to the community. People understand the need to support these programs and may be more likely to support kids before they understand the need to support adult artists.

However, we’ve realized that we can’t have all our foundation money continue on the same cycles that it has been in the past. They, too, have changed since the crash. You get out of cycles with people — we’ve had wonderful support from the Andy Warhol Foundation, but you can’t get it for more than three years in a row. You have to take a year off before you reapply, so that $50,000 certainly puts a hole in your budget. Or, the James Irvine Foundation gave us multi-year funding that tapers down. We used to get $75K or $100K every year, but this year is going to be $55K. So that’s another challenge. Just as you solve one funding issue, you face another. We are always looking into new opportunities, but who knows if we’ll be the ones to get it. We’ll do our best, of course.

I’d say we’re about a $1.3 million organization, which means every month we have to make over $100,000. We write four to six grants every month. There’s sort of an inverse proportion of effort to the value; sometimes it’s just as easy to write one large grant as is it to write a really complex small government grant for $1,000. So the big grants are sometimes easier to write, but there’s also a lot of competition for these resources.

Do you ever think about moving away from the nonprofit model?

AH: Getting a high degree of mission-driven earned income is not moving away from our nonprofit model. We still depend on a mix of earned income, individual donations, and foundation support. The benefit to that is that this mix allows us to be involved in more of parts of the community. But no, I don’t think that at this stage we could move away from the nonprofit model.

One of the most interesting things we’ve done is to take the workshop paradigm and mash it with the artist’s residency paradigm, because we didn’t always think of it that way. At the very beginning we didn’t know what our model was. We knew we weren’t certain things. We weren’t primarily a publisher, though we published some nice editions. We weren’t a rent-for-hire, because everyone had to go through portfolio review, and we weren’t just rent by the hour or something like that. The artists have 24-hour access, they have keys, they use the kitchen and other facilities. So the more we thought about it, the closest model that seemed to make any sense was the idea of artist’s residency, though traditionally those have been in rural areas, like an artist’s retreat. But we really think that because there are so many materials in the city, so many artists needed a new residency program in an urban environment. It adds a special kind of value.

When did you decide on that model?

AH: Well, I think it’s been a good 20 years or so. Kala became a member of the Alliance of Artists Communities 15 years ago. That’s where I said, “Oh, I found my people!” At the alliance, they’re such great problem-solvers, very creative people who have both the practical side and the idealistic side.

Nakano and I always thought printmaking was a great base and a good financial model. It is great to share equipment because nobody can use it 100 percent of the time. We don’t like seeing printmaking being put in an isolated container, separated from the rest of the art world. If printmaking is seen as part of the larger practice of contemporary art, then everybody gains, really. All kinds of people would like to make prints if they only knew how. People who make lots of prints already would also like the opportunity to create an installation or do a performance. So we’ve been able to support all those kinds of work with our fellowships.

How did you decide to expand?

AH: We had a list of about 25 reasons why we felt it was right to try to expand. We had 12 staff crammed into seven desks in two little offices. Our public programs were becoming too popular, so they were interrupting our resident artists at work because we didn’t have sound walls or anything. We needed a bigger, better gallery and more classroom space for kids and adults. We needed a meeting room for our 12 to 15 board members and staff since we didn’t have any place to meet other than in the artists’ workspace. We also needed better gallery storage, a kitchen area, public bathrooms, and private workspaces for artists. So for all those reasons and a whole bunch more, we decided to expand our space. Now our public face is all on ground level, while the quieter working spaces are up here on the third floor of our Heinz Street studio.

We arrived at kind of a stable place before the expansion — I think that 40 percent of our income was earned and about 60 percent was from grants and donations. Our goal was at least to get back to that balance. But we need a much larger amount of money because the whole operation costs a lot more. In the past couple of years we have been working hard to get back to 40 percent, and now we think — we hope — to hit 50 percent this year.

What have you done to accomplish that?

AH: Well, we’re selling more art — since we make the art here, we could support it. When we expanded, we got both a place where we could store the collections in museum conditions and store the work on consignment that we could show to potential buyers. We were also able to start custom printing. We either get people to pay us and they are the publishers of their own work and we are just the fabricators, or we publish a guest artist edition and we control and sell those publications through our art sales program. We’ve also been able to expand our classes and workshops. We mostly have classes on the weekends, and there are are only so many weekends. With the expansion, we were able to double or even triple our ability to host those classes. We’ve also accepted more artists as residents, we’ve started a membership program called Friends of Kala just this year, and we’re doing new fund-raising events and sales.

These big sales and auctions are partly aimed at helping us to develop Kala as a place where people come to buy art. So, we work with clients who buy retail and we also work with some art consultants involved in diverse projects. We want them to see us as a source where they can find a lot of artwork by a lot of different artists.

As part of that process of planning for the expansion, we wrote a pro-forma for five years where we planned out where our money was going to come from, how we were going to get there. So all of these different sources of income that I’ve mentioned were sort of planned out that way and we have, remarkably, been able to raise our earned income in the way that we planned.

Are you selling the bulk of your history?

AH: No, no, no. We are holding on to our collection. Someday, I hope, that will become an endowment for us, if we sell it to a big donor who then donates it, or to somebody who collects contemporary California work. But it hasn’t happened yet. Things like that always seem at least five years away.

When did you start paying yourself?

AH: I don’t remember exactly. I do know that I was the ninth employee, if that says anything. It’s been over 20 years now that we have been paid. I think it was somewhere after the first 10 or 15 years. Nakano and I would find a way to support ourselves by custom printing, teaching art, selling art, or other odd jobs to survive and also find a way to put money into the organization.

How has your life/work balance changed over the course of the past 30 years?

AH: Well, it’s very challenging to get my own artwork done, for one thing. During this whole 38 years I’ve done quite a bit of artwork but probably would have done more if I focused only on my own work. But, I also managed to get married late in life — I was 40 years old when I got married, and I had a child afterward, who is now 20 and is in college. So that was an interesting process to balance all of that. Fortunately my husband is fairly sympathetic with me working off-hours and not being paid a lot — I am probably the least paid person here, but we are going to change that eventually.

So you’re not paying yourself a full salary now?

AH: I won’t be doing my organization any service in the long run if I’m paid so little they can’t replace me when the time comes. But you have to build it up slowly. That was the one variable that I could control, and Nakano, bless his heart, that he did the same with me. So we’ve always paid other people more realistic wages. But we are hopeful that will change as time goes on.

“if you’re creating a platform for ideas, then new ideas have a base and a home already.”

What are some non-monetary payouts you receive?

AH: Oh! Well, it’s a privilege to work with all the great artists that come through here. We really have had some wonderful people come here and work. We have a fantastic staff who aren’t afraid to tell me what they think, which I am grateful for, but who also add so much value and so many ideas. I probably haven’t made as much artwork over the years, but I know I’ve learned so much from the artists here, over time, that I am sure my work has changed. I don’t know how — you can’t go back in time and take the road not taken.

The other thing is that there are people I know who every time they have a new idea, they start another organization. They go five years here, then five years there, and go on and on from there. I’m always scratching my head because if you’re creating a platform for ideas, then new ideas have a base and a home already. So rather than change organizations I feel like Kala gives us a base for us to do whatever we want, basically, come up with ideas and then try them out.

My husband says, “Aren’t you bored? You’ve been there 38 years.” But, it’s a new place every day because people come up with new artwork that’s being made, new projects are being thought up, new communities are being involved. Lately the Kala staff have really come up with lots of good ideas. So to me, it seems strange to go out and start something new. Why not make the best of what you have and help more people get going and doing more projects?

Comments (1)

Nice profile of an amazing Bay Area art asset and the woman who’s been at the helm. It’s a spectacular printshop and the gallery is an exciting addition to East Bay exhibition spaces. It’s interesting how this space started as more traditional printmaking studio and has grown to support such a range of activities and media–including video, photo, new media. Great info graphics too. I’d also love to see photos of Archana and Nakano at their earliest printshop. It’s hard to imagine the scrappy origins of such an established institution.