Looking at People Looking at Rothko

Occasionally, I find myself paying more attention to the visitors in a museum than to the works on view. Does this make me a voyeur? Maybe, but I doubt I’m alone. I don’t think there is any other art form that offers as much face-time with other people’s experiences — with the possible exception of the mosh pit at a rock concert. In the latter the audience faces forward, however, whereas in galleries and museums we move around and look in different directions, enabling us to interact with other viewers.

Over the holidays, I came across an exhibition that explores this subject — a series of photographs taken during the 1961 U.K. debut of Mark Rothko’s paintings at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, currently displayed in the gallery, along with recordings of visitors’ responses. Together these give a fascinating insight into what it might have felt like to stand before Rothko’s sublime color and vast scale in early ’60s Britain and absorb their intensity.

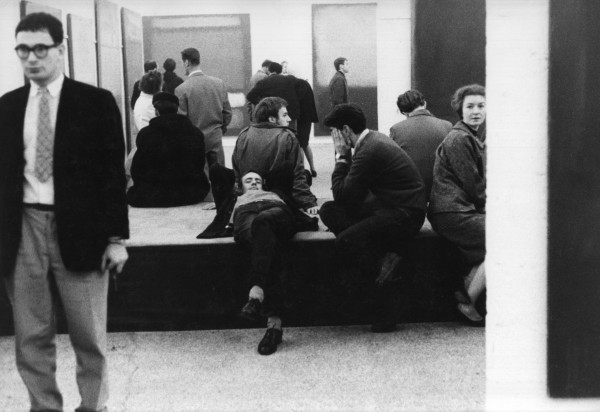

The photographer Sandra Lousada came to the 1961 exhibition intending only to see the paintings, but in an interview she describes taking pictures of viewers in the gallery as a reaction to what she saw. Though she took one black-and-white and one color film, only images from the former and a single photograph from the color series survive.

Often compositionally beautiful, the black-and-white images reveal onlookers lingering before paintings, leaning against gallery walls and columns, lazing on benches and soaking up the environment of Rothko’s work. Many appear lost in solitary reverie, while others lean toward others to share thoughts. My favorite: an elderly lady sprawled on a bench and supporting herself on an elbow, seemingly seduced or overwhelmed by what she sees. Or perhaps she is weary and wants to put her feet up. After all, to see a great exhibition is, as the critic Tom Rosenthal noted, extremely tiring.

It’s easy to project onto these figures, in their more formal attire, what it may have felt like to stand in their shoes — particularly those with backs turned, denying us a view of their facial expressions. This concealing of their thoughts is what makes them so compelling; it’s impossible in looking at them not to seek out signs of consciousness, or indicators of experience.

As a born-and-bred Brit living in the U.S., I’m fascinated by what it might have meant for someone in the U.K. to encounter such an expression of emotion at that moment in history. In 1961 Britain was just waking up to Abstract Expressionism; it was also the year in which a famous British-Soviet spy ring went on trial, the Beatles performed a legendary show in Liverpool, Sierra Leone and Tanganyika gained independence from the U.K., and “the Pill” became universally available.

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, Britain’s decreasing political influence, and — despite growing social liberties — the relentless grayness of its climate and daily life, what would visitors have made of Rothko’s paintings? Does context matter in this case? Rothko’s works, after all, speak to deeper emotional experiences — those of the unconscious mind. Many first-hand accounts describe quasi-religious encounters with his work, a response Rothko fully intended his viewers to have. Though it may be tempting to read certain contemporary political and other associations into Rothko’s works (such as the angst of the Cold War in some of his representations of the void, for example), was their astonishment simply because Brits had never seen anything like this before?

Among the letters and audio tapes included in the exhibition, I came across some powerful testimonies. The Cornish artist Peter Lanyon wrote, “I got visually drunk, and my eyes haven’t settled back yet.” Sandra Lousada claimed that it “affected the way I see for the rest of my life,” and the leading abstract painter John Hoyland wrote: “We were all reeling from the ’56 American Painting exhibition at the Tate. We didn’t understand it, we were mystified … [in ’61] we all knew Rothko had done something astonishing, of such intensity and mystery. To us they were gigantic paintings, environmentally engulfing. I’d never seen anything like it … We tried to apply all the lessons of analysis that we knew, and nothing fitted.”

Comments (6)

-

George Slade says:

November 3, 2025 at 4:59 am

-

Esther HUGO says:

January 24, 2012 at 9:21 am

-

Anna Hoeschen says:

January 21, 2012 at 5:36 pm

-

Ann Knickerbocker says:

January 18, 2012 at 7:41 am

-

M.K Hajdin says:

January 17, 2012 at 11:57 am

-

Megan Z says:

January 13, 2012 at 3:35 pm

See all responses (6)So pleased to have found this commentary on Ms. Lousada’s sharp set of artist spaces. Is this published somewhere? I found the portfolio on her website and would love to find it in print.

Rothko’s work certainly invites us to feel – but what? Perhaps that is the point. This insightful essay reminds us about the communal nature of experiencing art. It makes a difference to be a part of an audience and community, even though our reactions may be solitary.

I love seeing No. 14 1960 everytime I visit SFMOMA. Rothko’s work prompts and provokes such a feeling. I’ve always wondered how my reactions compare to others. Thanks for sharing such great insights!

Lovely essay. The audience reaction matters more than we think… and this was, as you note, a time when this audience was quite vulnerable to Rothko’s new power. Thank you for helping us see it as if we, too, are seeing it for the first time.

The mystery. That’s what gets me about Rothko, every time.

This reminded me of one of my favorite visitor pics: http://www.flickr.com/photos/thedirtycolumbia/5229440387/

The children look like an extension of the blue in the Rothko.