From Old Notebooks

I’m in Peet’s on Lakeshore, talking with everyone’s favorite podcaster and local historian, Liam O’Donoghue, and as I get up to leave, a man almost young enough to be my grandson smiles at me and asks me if we are radio producers or something. “No,” I say, and I tell him about East Bay Yesterday. Then he tells me he makes music. I’d love to hear it but I’m in a rush, and I scribble my name and phone number on a napkin. “Wow,” he says, looking at the napkin. “This is so poetic!” I laugh. It hadn’t occurred to me to do what he would do: just text it. I am still a paper person.

I go home and open the cabinet packed with my journals, forty years of raw material. The notebooks are filled with letters, receipts, pictures, my collages, newspaper clippings, pressed leaves and petals and doll clothes, and plenty of inky napkins. In there with all the grief about divorce, exile, and death, I find copious notes about daily life as a mother, a reader, and a walker in the city (including lists of the parks, public gardens, and libraries I love).

Linda Norton, Wite Out series, 1994

My Harvard and my Yale: the streets of New Haven, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Oakland, San Francisco, and other places in the US and in Europe; anywhere but white working-class Boston, where I grew up. Children and strangers and books and music and cities seem to have saved me from myself.

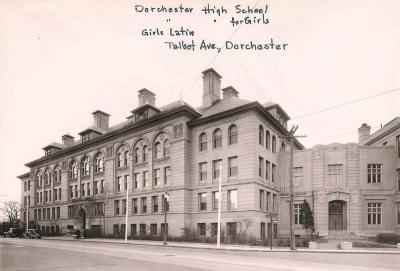

Out of a red journal from 2001 falls a sheaf of papers: my 1971 admission letter to Girls’ Latin in Boston, an elite public exam school, like Lowell in San Francisco or Stuyvesant in New York. The motto of Girls’ Latin, founded in 1877, forty-three years before American women were granted the right to vote: “Vita Tua Sit Sincera” (“Let Thy Life Be Sincere”). A nun at my parochial school had encouraged me and one other girl (there were 150 sixth-graders in our Catholic warehouse) to take the entrance exam. I’d found these cedar-scented documents buried in my mother’s hope chest.

I never enrolled at Girls’ Latin; our family, like so many other white working-class Catholic families in Boston, moved across the city line that year. An angry white neighbor (he’d heard we were fleeing) came to our front door one night that spring and threatened my father. “If you sell to the Colored, you’re dead.” My father, a scared working stiff, took the bus (or sometimes hitchhiked) six days a week to a job he hated. Most nights he walked up our street carrying a case of beer on his head, unhappy to be coming home to us.

We moved in June of 1971. In my notebook, I sketched out a plan to go back to our parish in Dorchester to live with my aunt so I could attend Latin. My mother found my notebook, gave me a slap, and badmouthed me for a few days. That was the first time writing ever got me into trouble. I entered seventh grade at a mediocre Catholic school where the emphasis was on obedience and anti-abortion; in anticipation of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the nuns and the monsignor separated us girls from the boys and sent us to the auditorium to watch a gory propaganda film about abortion. I had just had my first period when I learned that my uterus was a potential crime scene. That was awful to know. I prayed to the Blessed Mother (we never called her the Virgin Mary), who had never had sex. I thought that might be the best way to avoid becoming a woman.

Linda Norton, Wite Out series, 1994

I grew up in a Catholic world of immigrants from Sicily and Ireland and their children and grandchildren. At Girls’ Latin, I thought I might meet some of the Anglo-Saxon Protestants after whom New England streets and towns were named (there were many places with Indian names too, but almost no living Indian descendants). My heroes in those days (besides the Blessed Mother) were Irish rebel Bernadette Devlin and Brooklyn Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm. At Latin, I’d hoped I might meet girls and women as brave and smart as they were; maybe I could even become one.

I’ve spent almost no time in my life thinking about what might have been regarding Latin. I see these documents differently when I look at them now. I see American history past and present, and the arc of my own unlikely life, too.

March, 1971

Start with the congratulatory letter to me from perhaps the first MAGA politician in America, our Congresswoman Louise Day Hicks, former chair of the Boston School Board. Like other demagogues, Hicks was wealthier and better educated than most of her bigoted followers. Her personal life was characterized by contradictions (she was one of very few women in her law school class at BU; her best friends there were Jewish and Black; she was a feminist who was against abortion). To her followers she was just the person to protect them from the NAACP and the integration of the Boston public schools. Her dog whistles were subtle (“You know where I stand”) and not (“White women can no longer walk the streets [of Boston] in safety”). “Louise Day Hicks and the vociferous Boston Irish were like the dogs and hoses in the South,” wrote Fanny Howe, mother of three biracial children and a descendant of Boston’s founding fathers. “No difference.”

It was creepy, in 2019, to see Hicks’ signature on a letter that otherwise made me proud. Of course I knew all about the Boston Irish (that’s why I was interested in Bernadette Devlin, who was both Irish and pro-Black Panthers; I had no other model for that way of being).

Our favorite Irish cousins were some of the last white people in the housing projects. When we passed Black tenants in the hallways there, I would look down, ashamed because I knew what people like my mother and my aunts and uncles (including a Boston cop who worked “riot duty”) thought of them.

But one evening when we visited, there was a little Black boy sitting in my aunt’s crowded apartment, silently eating a tuna fish sandwich and watching TV alone in what we called “the parlor.” Crowded into the kitchen and back bedroom, the rest of us whispered in that “panic-stricken vacuum in which black and white, for the most part, meet in this country” (James Baldwin), amazed to be this close to the Other who seemed to define so much of our lives in that time of “unrest.”

I remember being surprised by the sandwich; my mother had told us many times to say “no thank you” when my aunt offered us something to eat, as she was raising five kids with no father then, and they never had enough food for themselves.

It turned out that the boy’s mother had had to go out to work that night and there was no one to watch her son, so she asked my aunt, who lived in the same corridor of the projects, to mind him for a while.

“‘Work’?” my mother said in a low voice. “Oh, is she a working girl?”

My aunt laughed.

What kind of work did the mother do, I wondered? Was she a nurse?

The next time we visited, my aunt had a stack of copies of Jet on her kitchen table. The boy’s mother had thanked my aunt with a bunch of crumbling old magazines. My mother and aunt sat at the table smoking and looking at the pictures, doing the impersonations I hated and enjoying old news about Pearl Bailey and Sammy Davis, Jr. But when they came upon a story about the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, my mother threw the magazine on the floor, disgusted that Till’s mother would let everyone see that horrible picture of his mutilated corpse.

“He shoulda kept his mouth shut.”

I think about those mothers — my mother, Till’s mother, and the mother of the boy alone with us at the apartment that night. Sometimes I feel that I have spent my whole life trying to understand that night and my place at the intersection of all of those lives.

Emmett Till in a photo taken by his mother a year before he was murdered in 1955 at fourteen.

The other documents in the sheaf include letters from the president of the Boston School Board and the headmistress of Girls’ Latin as well as a postcard about the first day of school, which I missed because we had moved so precipitously to a house right across the Fore River draw bridge near the main drag, route 3-A.

My Sicilian grandfather (born in 1885 when Emily Dickinson was still alive in Amherst and writing about that place she had never seen: “The Rose is an Estate — In Sicily”) had been a construction worker for the WPA on that bridge during the Depression. From our bathroom we could see it and the General Dynamics shipyard and the smokestacks at the Procter and Gamble factory where they made soap. The air we breathed there often smelled of low tide or Ivory soap or both, and we liked it.

•

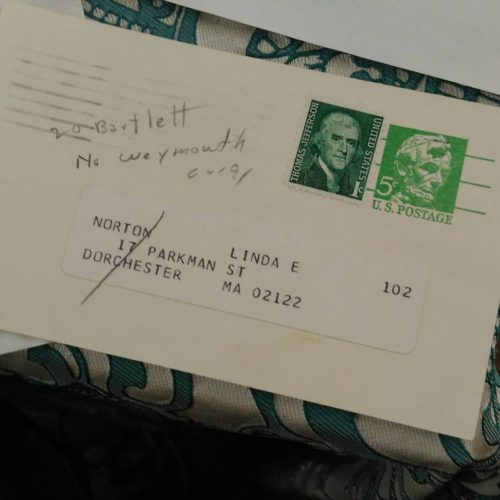

When I didn’t show up to take my hard-won seat in that class, the correspondence grew more urgent. The last postcard they sent is synecdoche for white flight and American history; our Boston address (our street, which was near Melville Avenue, was named after Francis Parkman) is crossed out; our new address is penciled in. The stamps on various pieces of the correspondence feature Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln (and Einstein).

In my notebooks, I find quotes from Jefferson’s “Notes on Virginia,” and collages I’ve made — in the 1990s with some Wite-Out and the face of Louis Armstrong on a pediment at Monticello, and in the 21st century, one with the head of Abraham Lincoln peering over a strafed battleground where hundreds of thousands died in a Civil War that happened long before anyone in my family came to this country; a war that continues.

Linda Norton, from the Dark White series, 2014 (CWF project in the Fruitvale District)

My parents ignored those notes from Boston Latin. Our family was in non-stop crisis: new house with one more bedroom (we five kids had all slept in one room in the house on Parkman Street); same hell for us. When neighbors called police on us because of loud, constant fighting and violence, I was both ashamed and vindicated; at least someone knew the truth about the way we were living. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know that the fight against lies required documentation.

•

This year, I scanned the documents and wondered who ended up taking my place at Latin. Someone richer, poorer, smarter; a girl from a family that valued learning? Latin was more diverse than the all-white high school I attended, but still it was overwhelmingly white (93.3% white, with the rest characterized as “Negro,” “Oriental,” and “Other”). The girl who took my place was probably white. Almost forty years later, about half of the current (co-ed) student body at Latin is white, though only 14% of all Boston Public School students are.

Students at Girls’ Latin in Boston, 1966

For twenty-three years I’ve lived in Oakland, three thousand miles away from New England, but still, when I meet Black people my age or older and I tell them I’m from Boston, they sometimes mention what was all over the news in those days: white people throwing rocks at buses of Black students in the 1970s or white boys attacking a Black man with a flagpole in that famous picture. It was 1976, the bicentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence (“What to the slave is the Fourth of July?“), and civil rights attorney Ted Landsmark was crossing City Hall Plaza when he encountered an anti-busing protest. The next day, Landsmark held a press conference, his face criss-crossed with bandages.

Linda Norton, from the series Dark White (Ted Landsmark’s face; after Ferguson)

I wrote in my notebooks for decades before I ever published anything (or wanted to publish). Even my published work still feels private to me, written for a small audience, including the dead. The conceit in my books is that I am talking to myself in my journals; but to make it work — to put all my people in one place, when we are never all together in real life or in history — I have to go through many, many drafts.

In my 2007 journal, I find things from my trip to post-Katrina New Orleans, where I found a water-logged Bible in the grass in the Lower Ninth Ward. I remember the pall over Oakland after the Santa Rosa and Paradise fires, and I wonder, what is the point of all this paper when everything is burning or drowning and there’s altogether too much “sharing,” too much stuff?

Linda Norton, Wet Psalm (New Orleans, 2007)

I worked at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley for fifteen years and I know the value of archives and documentation. It was at the Bancroft that I found a pamphlet of Amiri Baraka’s “Crisis in Boston,” a talk he gave in 1974 about class struggle and the need for poor white people to make common cause with Black people. It was there that I edited interviews with the first Black faculty and staff at UC Berkeley, most of whom spoke about Emmett Till’s murder and the photos in Jet as signal moments in consciousness and activism. In that library I read Gwendolyn Brook’s poetry about uprisings and Toni Morrison’s essays about the sickness of racism in America, the place where people like my parents and their parents “got white,” becoming heirs to and warped beneficiaries of a history that began hundreds of years before their impoverished parents arrived in Boston. Bereft: the word Morrison uses. Dangerously bereft.