We’ve Seen Too Much

I saw Susan Meiselas give a lecture the other day.

I return to her work often because it feels layered and processual. It’s clear how deliberate she is in constructing images that emerge from tricky ethical terrain. These include photographs of transient carnival strippers that predated academic and colloquial coining and use of “the male gaze,” ethnic violence against Kurds at the hands of Saddam Hussein’s government (and the power of the vernacular archival image), and almost real-time images of a popular uprising in Central America. In describing her work about those carnival shows to the class, she noted the presence of all matters of gazes and valences and relations, and then pointed out that “what was absent from the photographs is [the women’s] understandings of themselves.”

Susan Meiselas, Lena on the Bally Box, Essex Junction, Vermont, US, 1973, 1972–1975

The photo subjects are the ones who extend permission for your photo-taking, she told the class (and I’m paraphrasing). You won’t be there if they don’t want you to be. On one hand I believe her, at least I believe people ought to have agency and autonomy over their own likeness and representation. But on the other hand I wonder how true that is. The coloniality of the photographic gaze is inhered with an overreaching presumption of consent especially where marginalized subjects are concerned. “Imagine that the origins of the photography go back to 1492,” writes Ariella Azoulay. “Among [the rights of imperialism] are the right to destroy existing worlds, the right to manufacture a new world in their place, the rights over others whose worlds are destroyed together with the rights they enjoyed in their communities, and the right to declare what is new and consequently what is obsolete” (emphasis mine). 1

When Susan talked about her book Nicaragua — a book published in 1981 about the 1979 revolutionary uprising against the dynastic Somoza regime — she described a collaboration with a changing community, the “assimilati[on] of an unfolding history” into a frame that would be legible for unfamiliar audiences. She described her attempt to register with her camera the things she witnessed but couldn’t fully understand because of her outsider status.

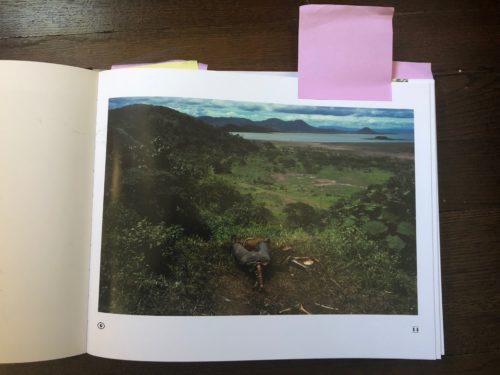

She discussed in detail two photographs in particular. The first, page fourteen of the book, is, in a word, haunting. It haunts her as well. The beautiful landscape is a hillside outside of Managua: Cuesta del Plomo, which translates to “hill of lead,” was a killing field and a known site of assassinations by the Nicaraguan National Guard. The foreground of the photograph is pure horror. The lower half of a human person still clad in jeans, a bare backbone the only evidence of what was once a functioning torso. Beside the body lie bones, an arm and a hand, darkened and decomposing in the sun. Her intention in taking that photograph, she said, was to clarify and justify the people’s struggle, to explain why they took up whatever arms they could find against the superior military might of the Nicaraguan state. This mutilated person serves a translational function for a US audience that has no understanding of “revolution” beyond the perverted founding mythos of our own country. The majority of US audiences do not understand the terror of the threat of being disappeared — these sun-bleached bones and bloated limbs were the final appearance of the disappeared. And as Nicaraguans were being disappeared by their government with the support of the tax money of the US audiences who would eventually see these images, that same money was also helping to fund Dirty War disappearances in Argentina.

The photograph is startling. I still find myself catching my breath even after seeing it dozens of times. But some of us who came of age during the War on Terror rather than the Cold War, we encountered videos of al-Qaeda beheadings before we could drive or vote. We might dismiss the illustrative power of a corpse in the moment that preceded the current moment, one that was not saturated with analogous images of suffering: a moment before we’d seen everything.

I don’t know the name of the man who inhabited the body, the body that remained in the jeans, and I don’t know what he might have done or thought, though I do know I wanted the body to be seen. This was a known site of execution. I often heard about such places. That body was left on the hill to terrorize everyone passing. […] For a long time I’ve lived with the inadequacy of that frame to tell everything I knew, and I think a lot about what is outside the frame, what is beyond this body […] Men and women were dismembered and never identified. I also think a lot about what else is outside the frame, such as the families, and how they watched people being pulled out of their homes, sometimes never able to find the remains. That’s not in this photograph. 2

The second photograph, page twenty-three, is one she describes as self-conscious performance. It is taken in the forests around Monimbo, a neighborhood in the city of Masaya, which is about fifteen miles southeast of Managua. It means “close to the water” in Nahuatl. There, masked resistance fighters, muchachos, are captured in the middle of a dangerous training with contact bombs. They are looking at the camera, not only aware of and permitting her presence, but fully aware of the meaning and potential of her photographing them in the act. They are posing for Susan, resistance fighters performing resistance fighter-ness for her and for their global audiences-to-be. They are creating the images of themselves they want viewers to see: we cannot see their expressions (are they grimacing, grinning, mournful? Does that actually matter?), but they are looking directly at a US public who will, for the first time, come to know what their government is doing in Nicaragua.

Forty years from the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional victory in 1979 (and thirty-two years since the end of the embarrassing Reagan-era Iran-Contra affair), Nicaraguans are still in crisis. Between the Aprils of 2018 and 2019, sixty thousand people have fled the country in the wake of political and economic destabilization. The afterlife of the civil war visually recorded in Susan’s book manifests in today’s migrant crisis. And as the current administration has worsened the crisis, images of detained children and fleeing families and corpses washing up from the Rio Grande have flooded our feeds.

Photojournalism evades a fair bit of ethical responsibility because of the liminal space it occupies between art/aesthetic and reportage. Are awards bestowed for the affective or informational qualities of a given image? Can we even unlink the two when aestheticized suffering becomes an attempt to manufacture a perfectly innocent and idealized victim(hood), and thus garner empathy?

The photograph of Yanela Sanchez that came to be emblematic of child separation policy was factually misleading. She was sobbing, distressed — the violent maintenance of US-Mexico border palpable within and emanating from her image. But the fact remains: she was not being separated from her mother. A correction was later issued, but well after the image had already been circulated worldwide.

Families languishing together in immigration detention is not a political victory, so one might argue that the stakes are too high here for what seems like semantics. But if we as photographers are missioned to tell people’s stories, are we not obligated to do so properly? There’s an absence, a void really, of care ethics in photojournalism. John Moore’s image of Yanela won 2019 World Press Photo of the Year and the €10,000 (£8,600) prize; apparently, you can, in a way, appraise and reward bearing witness to suffering. Reuters won a Pulitzer in 2016 for covering the European migrant crisis, and then again for “Breaking News Photography” in 2019 for the crisis at our southern border.

Photographs inform popular understandings of “refugee crisis,” “genocide,” “civil war,” “martial law,” “police brutality.” Susan doesn’t call herself a photojournalist; she gently and quickly corrected me when I accidentally described her work as such. While not being anti-technology, she sounded disgusted with the instantaneousness of digital image-making. She said that some (too many, I think) image-makers “assume the world is theirs to be eaten, spit out and shared”; that simply being in the world means that one automatically consents to being photographed. Her carefully cultivated method of patience and collaboration seems antithetical and almost antiquated to photojournalists contracted by news agencies and incentivized to be the first to break an image and/or a story; her work is not intended for speedy integration in a twenty-four-hour news cycle. We don’t have the ethical framework to consider the power of representation, she told the class. Her writing also betrays a growing pessimism, a generational concern/sensibility, and a reflection on competition to show sensational violence:

Thirty years ago there was optimism, and […] I’m not sure I have that much of it left. Optimism that a dictatorship could be overthrown, and that images could be made to interact in an environment that would create intervention, or the desire for intervention. It wasn’t intervention by ‘you’ for him as a victim. It was that ‘they’ lived that history and it was their consciousness that was already carried within that body. And so, in a way, the picture wasn’t for you to do anything. It was just to try to understand where ‘they’ were, the place from which they were acting. 3

Photojournalism is far from obsolete, but I guess I wonder about the changing role of the atrocity image, about what it means to show and attempt to humanize a dead person/body when slaughter is abundantly produced and corpses have never been easier to find. And in considering Susan’s position on image repatriation — on returning to find people in photographs as she did when she traveled back to Nicaragua in 1991 and again in 2004, in going back to a place more than once, in making the photographs usable for a country or for a community — for whom are these images and to whom do they belong and to whom should they belong? Are they for the subjects, for the photographer, for the audience?

I’m certain of nothing apart from the violence of the gaze that rewards and sustains/maintains itself; I’m uncertain whether form is more important than function, and I’m growing increasingly uncertain about the function of many of these images. These considerations have made me slow to pick up my camera again. I’m trying to convince myself this inertia is neither fear of the craft nor insecurity in my abilities, but an emulation of the same deliberateness I admire in Susan’s work. I haven’t convinced myself.

As we look at these images, images like many of Susan’s, “the moment of the other’s suffering engulfs us,” John Berger writes. And while we may try to assimilate facts presented by those images into our own lives, “the reader may tend to feel this discontinuity as his own personal moral inadequacy” (discontinuity referring to the way photographic permanence tends to excise a photographed moment from the moments surrounding it: the image, in a way, exists singularly even as we know events both immediately preceded and followed that moment). The image becomes a canvas for personal projections of morality. And once an image of atrocity is morphed into a universalizing reminder of the human condition, the moment effectively becomes depoliticized. 4 The first of the Four Noble Truths is that all humans suffer and suffering is an inevitable and inescapable part of life. But suffering is not homogeneous and it is not equally distributed; attempts at universality are shallow and foolish because of how sufferings are (and let’s be honest) hierarchized.

I think a lot about the images from Abu Ghraib. I remember seeing them on television when I was in middle school and being sad and confused at what I saw. I’m still confused. We saw naked men stacked on top of one another in human pyramids, others smeared with human shit, detainees forced into shoulder-dislocating stress positions, a uniformed man handcuffed and cowering from a German Shepherd; we saw men being punched, the sociopathy of imperial whiteness on full display with Lynndie England and Charles Graner and other guards smiling and posing with living prisoners and at least one deceased man. I didn’t learn any of the prisoners’ names until many years later. Ali Shallal al-Qaisi became a known name because of the photograph of him standing on a box in black ghoul-like garb with wires attached to his penis and hands that would, presumably, electrocute him if he moved. He was arrested and sent to Abu Ghraib when he attempted to tell foreign journalists that US troops were planning to use a plot of land to dump bodies of people they had killed. The international circulation of those images was probably well-meaning, but the images were “designed as theaters of humiliation”: they “not only document[ed] atrocity, they create[ed] it.” 5

What does it mean that these images intended for circulation within the prison became visible to the world?

“The pictures only show five percent of what’s happening to us,” al-Qaisi said in a 2015 interview. “The buzzing sound of the electric wires is still stuck in my head.”

What did we learn?

Pvt. Lynndie England (2003) surrounded by denuded Iraqi prisoners. The background is blacked out because they are not the subjects of this image: she is.

- From Arielle Azoulay’s “Unlearning the Origins of Photography” from the Unlearning Decisive Moments of Photography series.

- From Susan Meiselas's essay "Body on a Hillside" in Picturing Atrocity: Photography in Crisis (2012).

- Ibid.

- From John Berger's "Photographs of Agony" in About Looking (1980).

- From Peggy Phelan's "Atrocity in Action: The Performative Force of the Abu Ghraib Photographs" in Picturing Atrocity (2012).