The Centennials of Robert Duncan

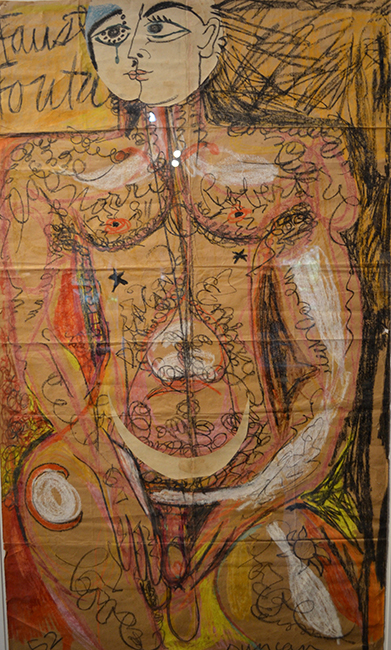

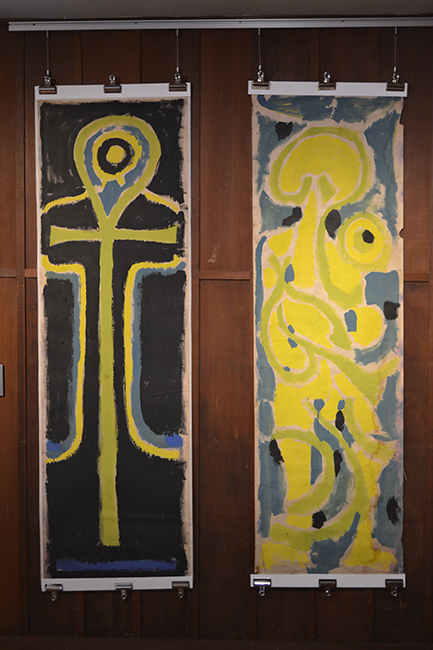

All images: Artwork by Robert Duncan on display at the Jess-Kael House in Berkeley, CA. Duncan image permission provided by the Jess Collins Trust.

On January 7, 1919, in Oakland, California, the poet Robert Duncan was born. In addition to a banquet of online commentary, the centennial of Duncan’s birth has occasioned at least three major gatherings, including Returning to the Field: Robert Duncan at 100 in Somerville, Massachusetts; a Robert Duncan Centenary Celebration hosted at Gibson Art Projects in Berkeley; and a three-day academic conference, Passages: The Robert Duncan Centennial Conference, convened in Paris by an international host of universities, including the Sorbonne and the University of Buffalo.

Spanning more than half a century, Duncan’s career intersected with, perhaps even defined, many of the most notable turns in the practice of US poetry. He endeavored with Robin Blaser and Jack Spicer as one-third of the Berkeley Renaissance during the late 1940s; with Charles Olson he taught at Black Mountain in North Carolina; he played a significant role in Donald Allen’s curation and editing of The New American Poetry (much in the same way that backseat drivers “play a significant role” in directing a driver — with cantankerous conviction). His trilogy of books from the 1960s exemplifies an anti-establishment mysticism consonant with the counterculture of the Vietnam Era. And the confrontation between Duncan and Barrett Watten at a memorial event for Louis Zukofsky has become the stuff of legend: “a small-scale re-enactment of the clash between the consecrated avant-garde, namely the aged New American poets, and the emerging new avant-garde, that is, the Language poets.”

I’ll admit that I’m not a Duncan scholar or even a Duncan enthusiast, but supported by funds from the Literature department of UC Santa Cruz (where I’m a PhD candidate), I traveled to Paris to attend Passages. Nominally, I went to present a short paper about Duncan’s relationship to New Narrative. I also wanted to know whether Duncan was still important to our current debates about poetry, and I wondered about his relation to the greater fate of the New American Poets. It was only four years ago, in the midst of a national conversation about racism and the history of US avant-garde poetries, that UC Berkeley was essentially forced to cancel its plans for an ambitious conference that would have marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Berkeley Poetry Conference. Events like this prompt my curiosity: will there be a place for Duncan and the New American Poets in future conversations about poetry? Need there be?

In DuBois’s Telegram, Juliana Spahr observes, “While there are a few exceptions, the New American poets tend to stay at home, their poems tend to be located in the United States, and, especially when compared to avant garde modernism, are notably monolingual.” Whether it’s “globalization” or “the internet of things” or “the anthropocene” or some other keyword that articulates the stakes of common cause today, the mindedness of The New American Poetry seems today especially provincial, perhaps nationalist or even imperialist. Infamously, among scores of poets, Allen’s anthology included only four women (Helen Adam, Madeline Gleason, Barbara Guest, Denise Levertov) and one poet of color (LeRoi Jones). Joanne Kyger — bless her — wrote to Don Allen in response to her exclusion, “I guess you’re just not interested in interesting poetry.” Interesting, here, would include so many of those voices of the marginalized and devalued and delegitimized.

A stark irony of The New American Poetry, then, is the influential anthology’s limited relationship to the margins, and how continuous was its dialogue with the old American poetry — if not formally, then in other ways. In retrospect, does Don Allen’s “interest” diverge so much from the elite gatekeeping that supported the old Modernists? Allen thought his anthology might sell a couple thousand copies; if it had, readers and critics would not likely be returning to its table of contents with such scrutiny and contempt, as radical as it may have appeared in its time. For my part, I had avoided Duncan because I figured him as part of the trouble, part of the tradition that makes it impossible to speak profitably about the history of poetry without certain (white) (male) geniuses. I too wondered, might it be time, might it be just, to leave him behind?

Scheduled immediately preceding Michael Palmer’s keynote address, the New Narrative roundtable was the final group presentation at Passages. I tried to articulate the concrete connections between Duncan and New Narrative. I highlighted, for example, that it was the day following the Duncan/Watten conflagration that Steve Abbott and Aaron Shurin began their three-day conversation with Duncan that would subsequently be published by Gay Sunshine and significantly inform Duncan’s recuperation as a gay literary icon in the late 1970s. I ended my talk with a big gob of Bob Glück, including his recollection, in Communal Nude, of Kathy Acker’s meeting Duncan: “Kathy thought Robert was ‘fabulous,’ advised me to sleep with him, and said that she would absolutely.”

This was also my chance to discuss one of the most challenging pieces from Duncan’s writings, his essay “The Homosexual and Society,” published in Politics in 1944, and later revised. Analyses by gay critics, such as Robert K. Martin’s The Homosexual Tradition in American Poetry and Thom Gunn’s “Homosexuality in Robert Duncan’s Poetry,” both originally published in 1979, suggest Duncan’s essay prefigured the Gay Liberationist themes that would emerge a quarter-century later. But critical and political celebration of Duncan stemming from an appreciation for “The Homosexual and Society” can only be done by way of qualification; Duncan’s sexual politics are transcendent, taking issue not merely with the straight world, but with the “homosexual cult” that elevates itself away from and outside of that world by way of camp and other modes of gay self-definition, which Duncan characterized as “loaded with contempt for the uninitiated.” As Jennifer Moxley has written, in a tender final letter to Kevin Killian, “Several of the gay male scholars seemed conflicted or unhappy about Duncan’s 1944 essay, ‘The Homosexual in Society.’ They thought it might be homophobic (or self-hating?). They were uncomfortable with Duncan’s critique of the so-called ‘cult’ of homosexuality. I couldn’t help wondering, would they have had the courage to write that essay?” In my paper, I sought to mainly represent Bruce Boone’s reflections on Duncan’s essay, hoping to communicate a certain ambivalence between the gay generations. Writing in 1983, Boone seems to celebrate “The Homosexual and Society” as evidence of a rich dissensus within sexual politics (thereby finding a way to make use of what he sees as the problem in Duncan’s thinking). What I take from this encounter: sexual politics are not one, but many. And it is through Boone’s critical analysis (his making or poesis) that “The Homosexual and Society” becomes a tether that can bind Duncan’s transcendent idealism to New Narrative’s conditional materialism, that can hold the generative possibilities for solidarity even given the contradictions of these positions.

Having gone to Paris thinking I might be witness to the end of the Duncan industry, I was to be sorely disappointed. And was I made glad by that disappointment? Yes, absolutely. Duncan’s corpus, elaborate and various, provides a stage for the big-hearted, the book-minded, and the eccentric to play out their dramatic arguments about language, sexuality, the fate of modernism, kinship, death, revolutionary change, and derivation.

I cannot do justice to any of the conference’s talks here; the best academic papers are performed as much as read. They earn their word counts and footnote volleys. But I did see new futures for Duncan on full display in the work of Sarah Ehlers and Eric Keenaghan, for example, whose monographs went to the top of my must-read list. Both papers appeared on the same panel regarding Duncan’s politics and demonstrated the pleasures of fostering a deep (perhaps even obsessive) commitment to one’s subject matter. Ehlers examined the oft-overlooked poems of Duncan’s undergraduate years. Given my superficial introduction to Duncan’s poetry by way of occultism over the years, I was pleasantly surprised to hear the closing quatrain to “A Campus Poet Sprouts Social Consciousness”: “Down with the rich, up with the poor / let the bosses shovel manure! / Let the bosses give way to the Masses / the world will be ruled by the lower classes!” Observing that the “legacies of literary modernism have […] made proletarian poetry a hard pill to swallow” Ehlers provocatively returned to Duncan’s early poetry as a “performance of proletarianism,”a performance that “simultaneously critiques cultural front aesthetics and participates in what Rachel Rubin and James Smethurst have identified as the kitschy and campy aspects of US cultural left productions.” Keenaghan brought us up to date, acknowledging the violent homophobia and transphobia that define the “dark times” we struggle to make sense of, so that we might defeat them. He spoke slowly, clearly, and passionately: “My talk today follows [Hannah] Arendt’s suggestion to avoid searching for solutions but instead to risk speculation about what one special figure’s life and work suggests about these dark times. Whatever Robert Duncan can illuminate for us now about poetry’s political life in relation to our predicament would be useful, no matter if he proves a bright-burning star or a weakly flickering tapir.”

Theosophy, competing theories about value, and granular arguments about psychoanalysis: academic conferences can be the elite intellectual sphere that the general public assumes them to be. That’s fine by me, but my ears really perk up when someone has a juicy portion of gossip to pass around. In Paris, this came in the form of a moving and elegant talk by Alice Fahs and Mimi Chubb, respectively the daughter and granddaughter of Ned Fahs. Fahs was Duncan’s lover and TA while he was an undergrad at Berkeley in the late 1930’s. Duncan left Berkeley to make a life with Ned, a passionate and formative affair that eventually flamed out. Following a brief attempt at East Coast living and a few months of compulsory service for the United States Army (he was dishonorably discharged for homosexuality, or, in his words, for being “a sexual psychopath”), Duncan went back to California and Ned went back into the closet. Alice Fahs became aware of her father’s sexual and romantic history only after his death. (An old photo album with pictures of Ned with his Navy buddies clued her in to there being something queer afoot.) At the University of Buffalo, Fahs and Chubb learned more about Ned’s past and this fabulous poet who was Ned’s lover. Their research presented new ways of reading even the most famous of Duncan’s poems, such as “The Torso: Passages 18,” which slyly points to Ned through a citation of Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward II (lines spoken by King Edward’s possible lover, Piers Gaveston). This was a talk that completely inverted the purpose of this celebration of Duncan and his career: there’s actually still so much to learn about him and his life. Duncan is not a settled matter. He continues to be part of the collective life of poets and poetry — in this case, even a part of family lore.

In the process of writing this essay, I found not one but two copies of Robert Duncan: Drawings and Decorated Books, edited by Christopher Wagstaff and printed in concert with an exhibition at UC Berkeley’s old University Art Museum and the Bancroft Library. (It’s still possible to find little literary gems on the shelves of used books at Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue, in Berkeley.) I bought one copy for $15 and left the other one, which cost a bit more but was signed by Virginia Admiral and Robin Blaser. By the time I found Wagstaff’s slim volume, the exhibition of Duncan’s crayon drawings at Gibson Art Projects had been closed for some weeks already. It was a humbling reminder, this evidence of Wagstaff’s decades-long dedication to Duncan. As much as power and tradition were on full display at the Sorbonne (the kind of power that necessitates a parenthetical or an asterisk because it is, finally, the ambiguous power of the academy), there was also love for Duncan and the stage he created for others and himself, so that future thinkers would be able to produce with criticism, music, and determination the “bright-burning star or a weakly flickering tapir” Keenaghan suggested in that overheated little room in Paris, now some months ago.

Wagstaff writes, “In 1951 Duncan began using a new kind of crayon made of beeswax and oil by Gui de Angulo, who recalls warning the poet that the drawings he was doing with children’s crayons would not last: ‘To show him I put some of his colors on a piece of paper and laid them out in the sun, and by the next day some of them had faded. He was impressed. It was then I made the special crayons, just a few at first, which Robert began playing around with right away.’ De Angulo’s crayons were softer and creamier than children’s crayons, almost like tubes of paint. The painter Lyn Borckway recalls that ‘if you picked up one of those sticks of color, you just couldn’t stop but went on obsessively by the hour.’”

I could have used this introduction to Duncan’s visual art practice back in April, when I first saw a selection of Duncan’s drawings at the Gibson Art House. A panel had been assembled featuring tributes and readings by Joanna McClure, Norma Cole, Lawrence Jordan, Wagstaff, and Jack Foley. Listening to Norma Cole makes me swoon, and I lapped up the air between the words as she spoke: “There was a big trunk at the end of the bed. I sat on the trunk, and Robert was asleep under the afghan. I thought he was asleep. I was looking around. I was amazed. I was looking at everything, and suddenly Robert said ‘come over sometime, anytime you want. Just come and look at books and whatever.’ It was a family thing. Robert and Jess were the most like my mother and father that I never had. So I was hooked.”

When Norma and the other panelists finished, I gathered my things and almost bolted to the door, hoping to avoid the post-reading schmooze that follows most literary gatherings. I want some sun, I thought. But there was Kevin Killian, who introduced me to someone fabulous (whose name escapes me now) and tried to pay me for my contribution to the most recent issue of Mirage #5/Period(ical). I couldn’t take his money after all we’ve done together, and I told him so. I hugged him and swiftly exited. In an email exchange a few days later Kevin wrote, “Eric, that’s not how people prosper, running from cash.” About a month later, Kevin would leave on my voicemail a final recording for me, talking about the effect of Duncan’s eyes on a younger Dodie Bellamy, who briefly sat in on one of his classes. He was making a plan for us to gather in July to work on a new edition of one of his most beloved projects. Like Norma was to Duncan, I was to Kevin: hooked. There are these writers who provide us a body of work so grand and various we can cast our thoughts and feelings upon them like we would a stage. Duncan has been one of those figures in the past. May Kevin be one for the future.